| |

|

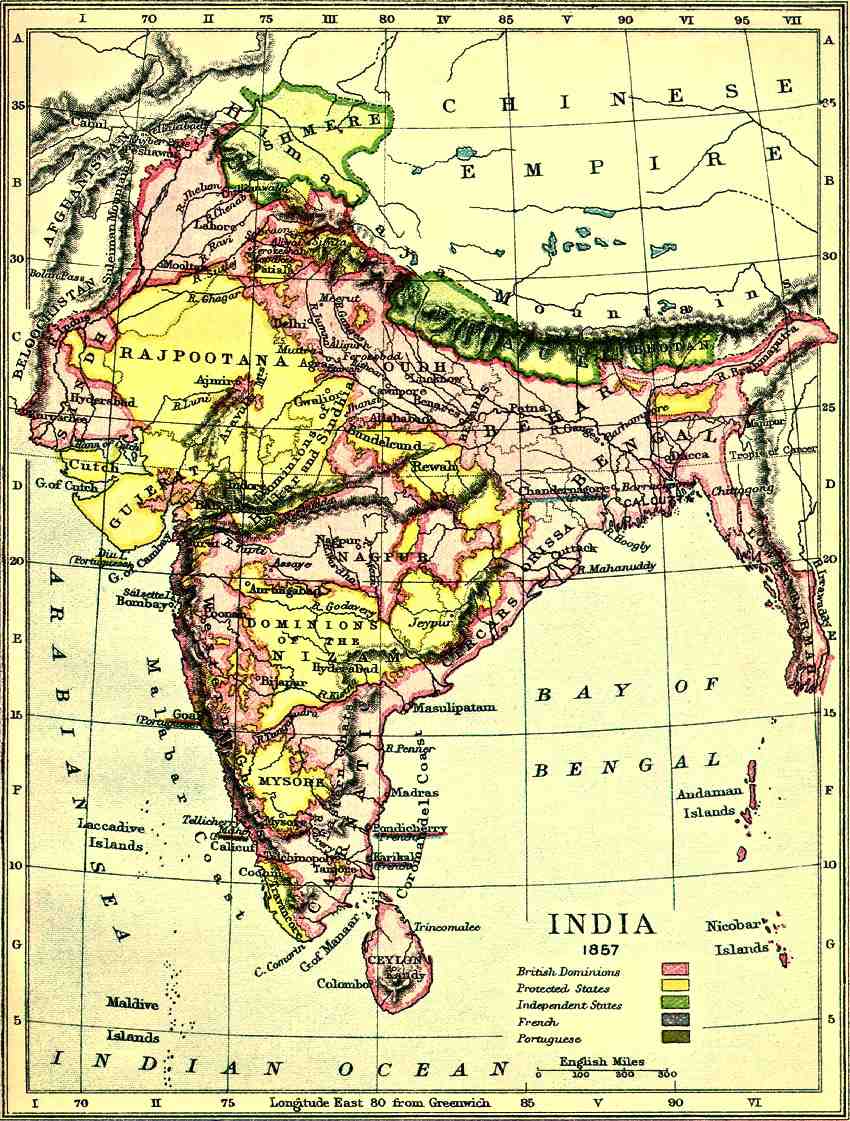

India 1857 |

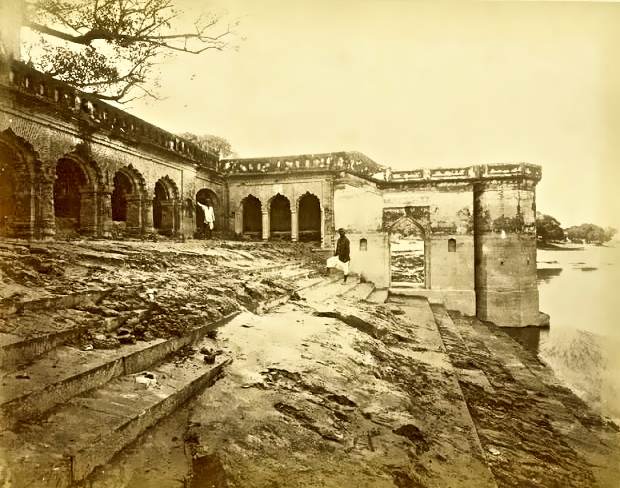

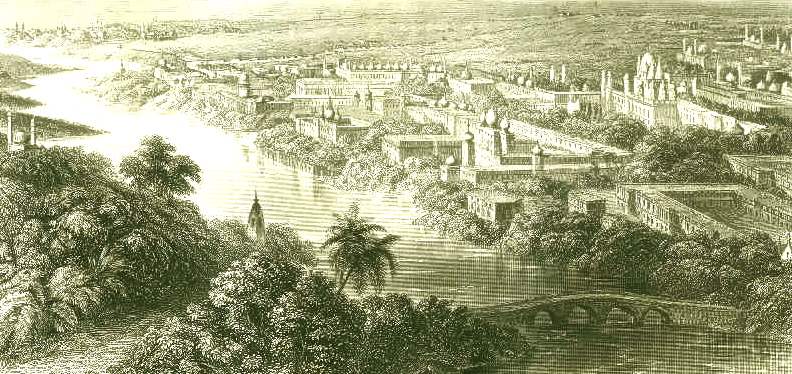

Ganges River |

|

The East India Company is, or rather

was, an anomaly without a parallel in the history of the world. It

originated from subscriptions, trifling in amount, of a few private

individuals. It gradually became a commercial body with gigantic

resources, and by the force of unforeseen circumstances assumed the form

of a sovereign power. — Bentley's Miscellany (1858)

The East India Company was a massive export company that was the

force behind much of the colonization of India. The power of the East

India Company took nearly 150 years to build. As early as 1693, the

annual expenditure in political "gifts" to men in power reached nearly

90,000 pounds. In bribing the Government, the East India Company was

allowed to operate in overseas markets despite the fact that the cheap

imports of South Asian silk, cotton, and other products hurt domestic

business. By 1767, the Company was forced into an agreement that it

should pay 400,000 pounds into the National Exchequer annually. |

East India House - Leadenhall Street, London (1817) |

| The Company was just as adept at playing politics abroad. It

distributed bribes liberally: the merchants offered to provide an

English virgin for the Sultan of Achin's harem, for example, before

James I intervened. And where it could not bribe it bullied, using

soldiers paid for by Indian taxes to duff up recalcitrant rulers. Yet it

recognized that its most powerful bargaining chip, both home and abroad,

was its ability to provide temporarily embarrassed rulers with the money

they needed to pay their bills.

|

|

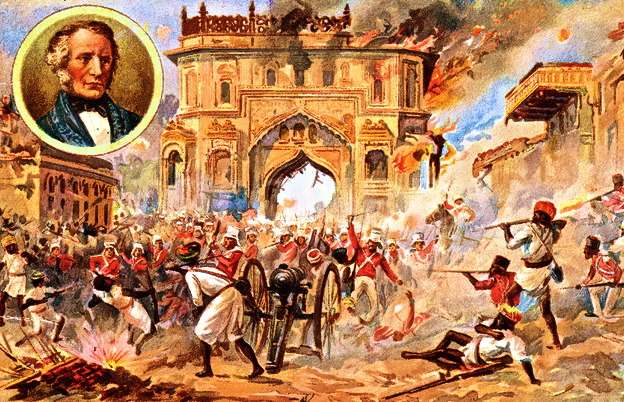

In January 1857, at the Dum Arsenal near Calcutta, an

Indian Lascar (sailor) asked a Brahmin Sepoy (infantryman) for a drink

of water from his brass cup. The Brahmin refused to share his cup; to

share his cup with a Lascar would contaminate it because of the Lascar’s

lower caste. In anger, the Lascar declared that the Brahmin would lose

his caste anyway when he used his new Enfield Rifles because the

cartridges contained animal fat from both pork and beef. This

announcement alarmed the Brahmin who confided his fears to his fellow Sepoys.

For a long time unrest and discontent had been rife

throughout India due to various territorial annexations, dethronements

of rulers, and other injustices on the part of the East India Company.

The revolt was mainly confined to the Company's Bengal Army, and its

immediate cause was the introduction of cartridges lubricated with pigs'

and cows' fat, and therefore taboo to both Moslems and Hindus.

Eating pig flesh is an abomination to Muslims, and the Hindu religion

regards the cow as sacred and therefore banned the consumption of its

flesh. Withdrawal of the cartridges did not remove the unrest, and on May 10th,

1857, the native garrison at

Meerut, the largest military station in

India, released eighty-five of their comrades who were in jail for

refusing to use the cartridges. After killing some of the British

officers and their families, the mutineers rode to Delhi. |

|

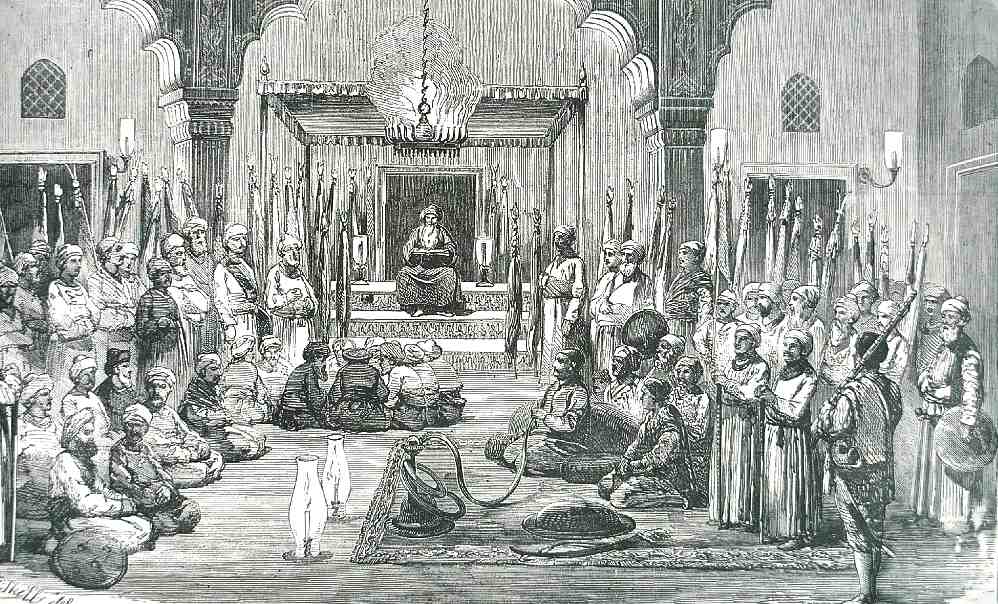

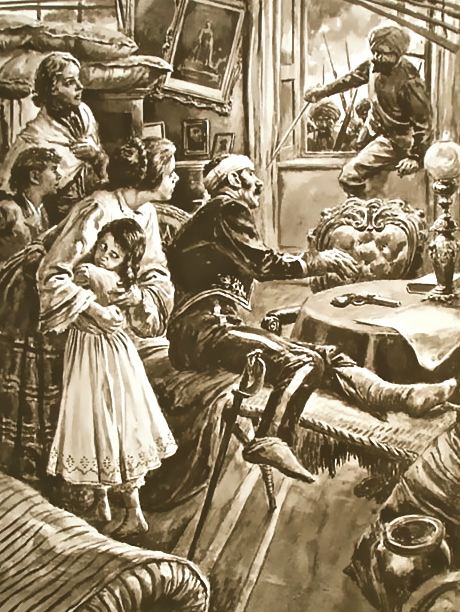

By 1857, the Mogul dynasty had withered to the point of

near extinction. The last of the Moguls, Bahadur Shah II, 'King of

Delhi', was a frail, opium-addicted old man deprived of any real power.

A pensioner of the British, he was king in name only, and it was

understood that upon his death his title would no longer exist.

|

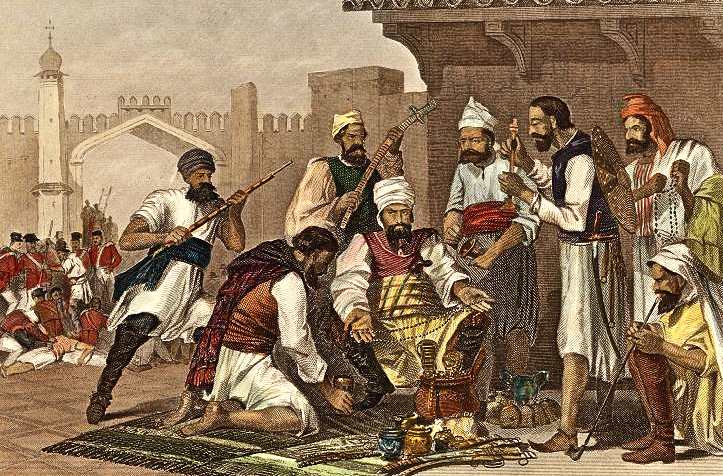

Bahadur Shah II - King of Delhi (Last

Mogul Emperor of India) |

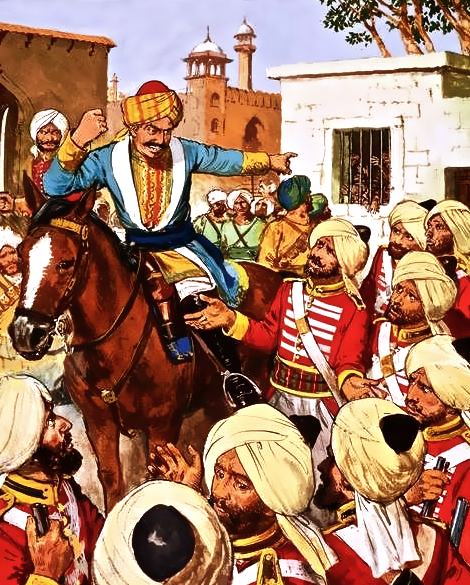

| In the early hours of May 11, 1857, the King was jarred from his rest

when news flashed through the court that the 3rd Native Cavalry from the

nearby Meerut cantonment had dashed to Delhi and entered the city by the

bridge over the Jumna River. |

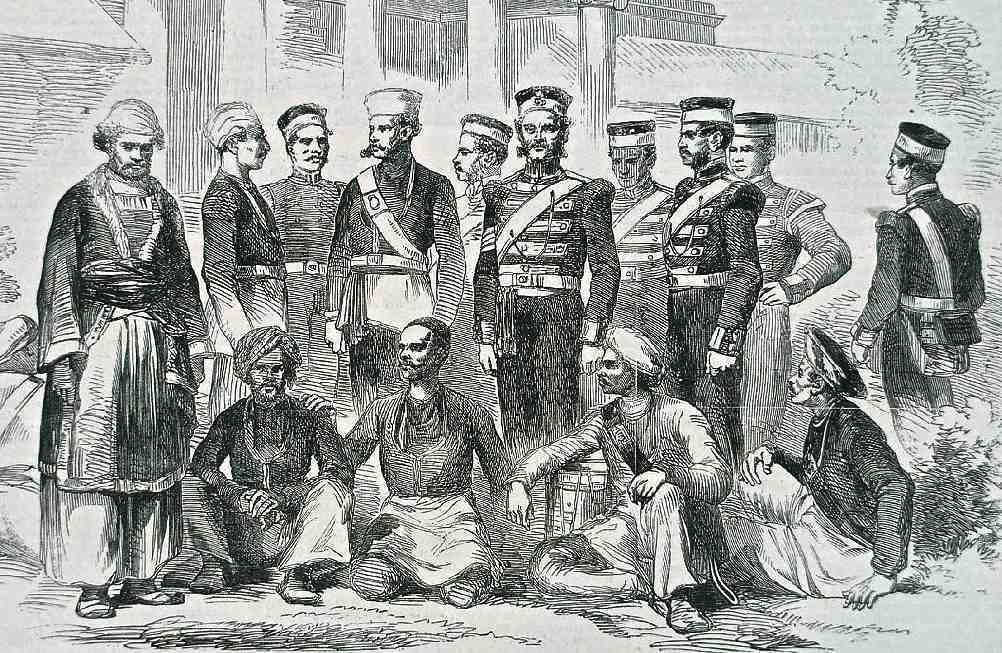

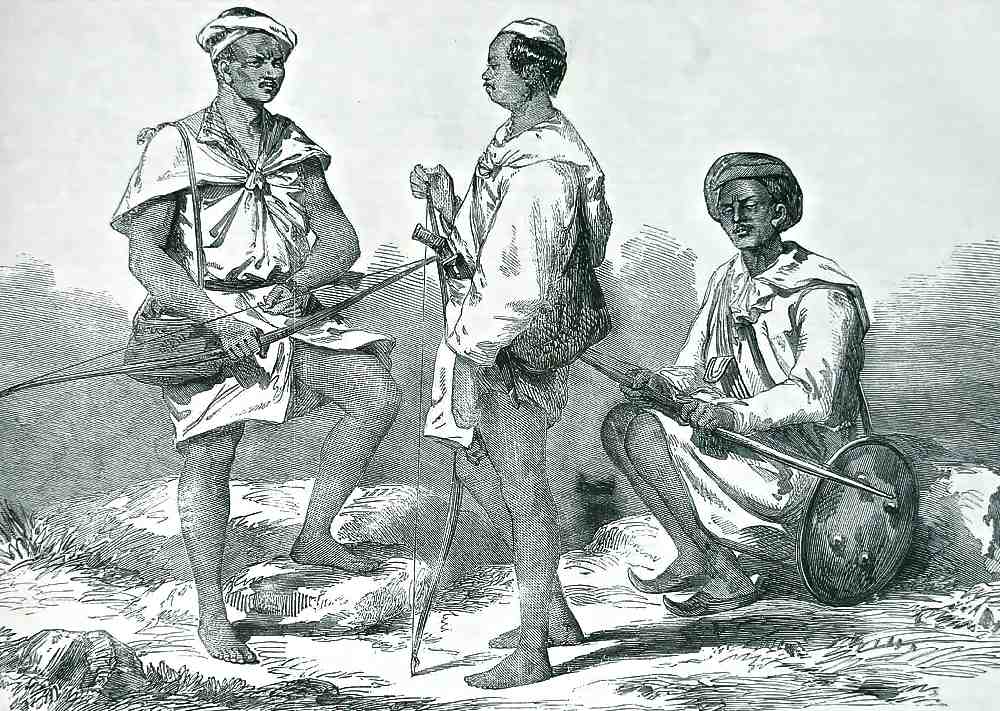

Mounted Rebel Sepoys - Delhi |

Bahadur Shah was hesitant to accept leadership of the

uprising. It would mean exchanging a peaceful life that permitted him to

write poetry in his luxurious palace for a life promising only risk and

turmoil. But he had no choice, because he was, in effect, a prisoner of the

mutineers. The 3rd Cavalry, now running wild in Delhi, would inevitably

be joined by all native units in northern India, he was told.

The native garrison at Delhi joined them, proclaimed the King of Delhi

as Emperor of India, and massacred the British residents. That attack

was only the beginning. Massacres, including the killing of women and

children, erupted throughout Delhi. Many of the resident British army

officers and civilians were hunted down and murdered on the streets of

the city.

Now titled the Emperor of Hindustan, Bahadur Shah did not intervene when

a group of Europeans who had sought sanctuary in his palace were

butchered to death. A steady stream of mutineers from across Northern

India headed to the impressive walled city of Delhi. It seemed as if

they had indeed taken the East India Company by surprise. |

|

A small group of officers and men managed to stop the city arsenal

falling into mutineer hands, but only by blowing it to pieces. Several

hundred mutineers died in the conflagration, but some of the defenders

also shared the terrible fate.

Lieutenant Edward Vibart of the 54th Native Infantry, witness to this

tableau of horror, later described it, "The horrible truth now flashed

on me — we were being massacred right and left, without any means of

escape! I made for the ramp which leads from the courtyard to the

bastion above…Everyone appeared to be doing the same…the bullets

whistled past us like hail. To this day it is a perfect marvel to me how

any one of us escaped being hit."The rapid spread of the mutiny in

North India provoked unprecedented urgency in the British. Army

reinforcements were rushed from Rangoon, Ceylon and the Madras

Presidency in South India. |

|

Siege of Delhi - Kashmir Gate . . 1857 |

The British regarded Delhi as particularly important for symbolic and

strategic reasons. If it was not soon retaken, the Punjab and Northwest

provinces might be encouraged to revolt. Sixteen years earlier, during

the First Afghan War, the Afghans had wiped out a British army, and with

it the myth of British invulnerability.

The city of Delhi was surrounded by 12-foot-thick walls and defended by

a few thousand well-trained Sepoys, although local volunteers up to a

total of perhaps 40,000 men supported them. The British had too few men

(approximately 10,000) to fully surround the city, so Indian

reinforcements and supplies were never cut off. Neither did the British,

at first, have sufficient artillery to breach the walls. Further, the

summer heat reached at times a reported 140 degrees.

The British occupied the old military cantonments outside the city, on

what was known as the Ridge. As a gesture of defiance, they burnt the

barracks - and left themselves without shelter from the grinding sun

which was to beat down upon them for over three months in the hottest

season of the Indian year. It was soon obvious that the British were not

strong enough to take Delhi. The mutineers forces were

increasing every day as more and more reinforcements came in brigades of

cavalry and infantry, their regimental colors bearing the names of

British victories flying bravely, their bands blaring British marching

tunes.

June 23rd, 1857, the 100th anniversary of the British victory at the

Battle of Plassey, which had marked the completion and

consolidation of the British East India Company's control over India,

was a difficult day for the British. On this day, bazaar folklore had

it, the British Raj would be driven from the subcontinent. In what may

have been an attempt to fulfill that prophecy, the Sepoys launched a

particularly savage attack on the Ridge. The British won the day,

however, driving the attackers back to their Delhi ramparts. |

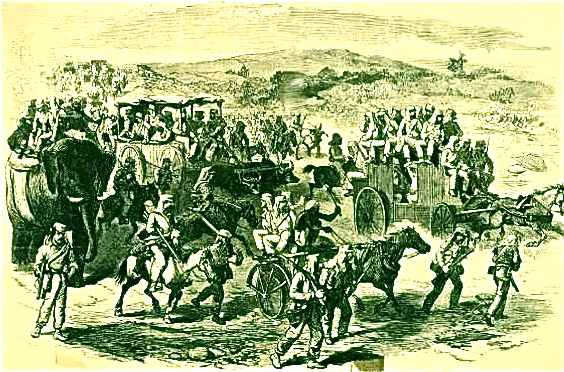

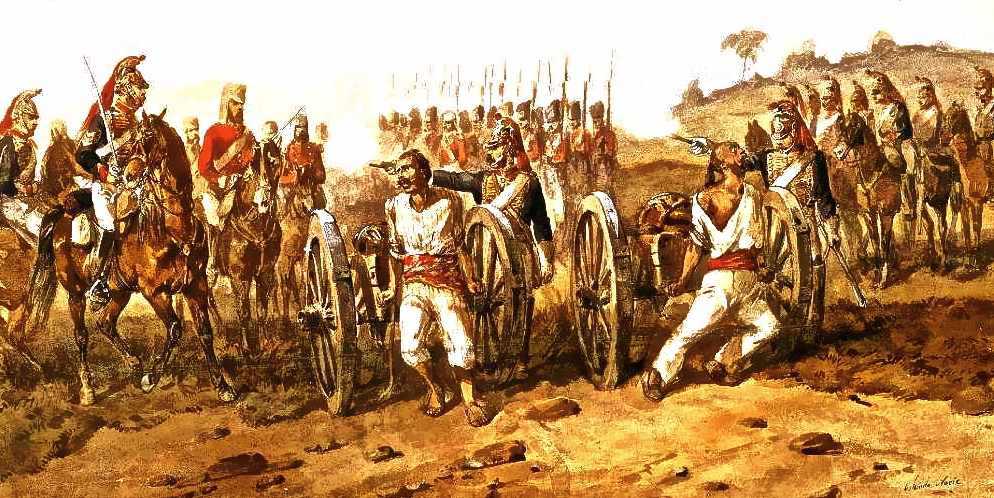

March to Delhi - 1857 |

The British had to have reinforcements and heavy artillery with

which to breach the walls of Delhi, and the reinforcements could only

come from the Punjab. A massive siege-train was organized; great guns

drawn by 16 elephants and accompanied by over 500 wagons loaded with

ammunition sufficient, it was confidently stated, "to grind Delhi to

powder."

General Sir George Anson, Commander-in-Chief India, received orders on

May 12th, 1857, to besiege Delhi. With considerable speed he organized

what became known as the Delhi Field Force. It consisted of the 9th

Lancers, the 75th (Gordon Highlanders), two Royal Horse Artillery

troops, the 1st and 2nd Bengal Fusiliers (European), 9th Light Cavalry,

and 4th Irregular Cavalry. Of the two native infantry regiments present,

one mutinied and cleared off to Delhi while the British disarmed the

other. At Baghpat, Colonel Archdale Wilson joined the Field Force with

the remnant of the Meerut garrison, consisting of two squadrons of the

6th Dragoon Guards and part of the 60th Rifles. On September 3rd and

4th, 1857, the British siege train arrived and began its work. |

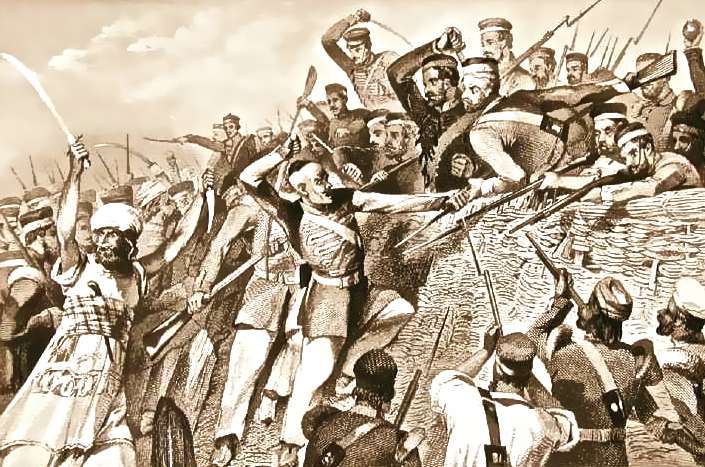

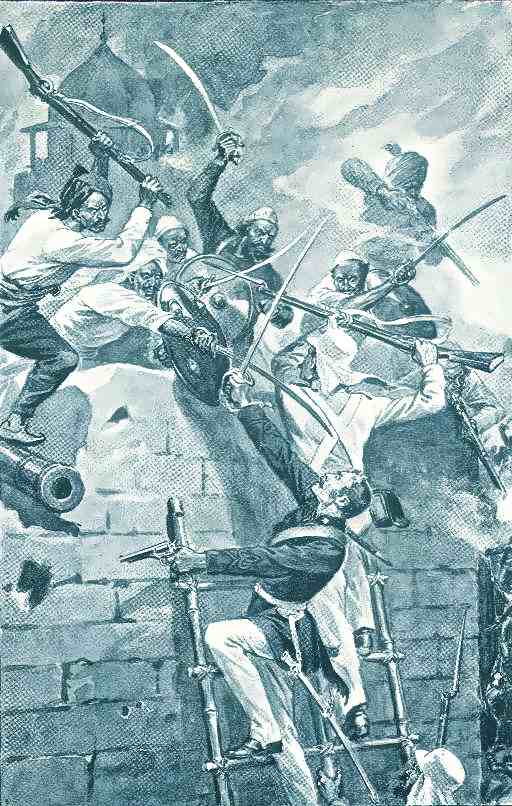

Kashmir Gate - September 14th, 1857 |

Lahore Gate |

Brigadier General Wilson, in command, ordered an assault for dawn on

the 14th of September, 1857. Four columns were to attack. Three columns

side by side would hit the northern walls at the Kashmir Gate, Kashmir

Bastion, and Water Bastion, while the fourth column would swing farther

south to try and force the Lahore Gate.

The attack got off to a bad start. The defending mutineers produced

deadly rifle and artillery fire, while men carrying the scaling ladders

could not keep up with the leading troops. The Kashmir Gate had to be

blown up by engineers, and that column wormed its way into the city

while the two other northern columns exploited the breaches. Once

inside, the three northern columns met near the Anglican church and set

up a perimeter. By day’s end almost 1,200 men had been killed or

wounded.

British troops found the magazine that had been blown up at the start of

the mutiny only partially damaged and a large store of artillery and

powder had survived. This allowed the force in the northern part of the

city to blast their way southwest to link up with the column attempting

to force the Lahore Gate. It had not been taken in the opening assault,

but finally fell to British forces on the 19th. That proved to be the

end of the mutineers’ resistance. On the 20th British troops blew open

the gates to the Red Castle to find the citadel deserted. Bahadur Shah

and his retainers had fled in the night. |

|

The "King of Delhi" Captured |

Bahadur Shah, disillusioned and tired of being manipulated by the

sepoys, had hidden a few miles north of the city in Emperor Homayun's

tomb. This was discovered by the intrepid but headstrong Major William

Hodson, who was famous along the Northwest Frontier as the leader of

hard-riding irregulars known as Hodson's Horse and who now managed

intelligence for the British at Delhi. With 50 of his men he set out on

September 21 to bring in the errant king.

Bahadur Shah had huddled inside the cloisters of the tomb while

thousands of his servants and well-wishers sullenly watched the

approaching British horsemen. The king knew that resistance on his part

would be pointless, and he accepted Hodson's promise that the major

would spare his life if he gave up quietly.

Followed by a vast entourage of Indians, Hodson led his captive back to

Delhi. Then, he and 100 of his irregular cavalrymen returned to

Homayun's tomb, this time to bring back the king's two sons and

grandson. Despite a mob of royal retainers and partisans, many of whom

were armed, Hodson was able to flush the young scions of the Mogul

dynasty from their hiding place. Hodson, surrounded by a hostile crowd,

did something that has ever since been criticized but may have saved his

life and those of his escort — he raised his carbine and summarily

executed the three princes. Amazingly, the shocked mob did nothing.

Hodson, as he had done many times before, stunned his adversaries into

submission by sheer audacity. The bodies were dumped unceremoniously at

the spot where the king's sons were thought to have committed atrocities

against the English. As the British chaplain observed, 'It was a dire

retribution.'

The seat of the once-great Mogul Empire was forever gone.

With the Delhi under control, 2,800 soldiers were dispatched to aid in

the relief of Lucknow. Although the mutiny went on for several more

months, the British recapture of Delhi marked their reconsolidation of

power.On September 14th, the day of assault, till the 20th, when

Delhi was completely under British possession, much looting took place

in the city. |

Eldest Son - King of Delhi |

| The troops, both European and native, and especially the Sikhs,

entered houses during those days and managed to secrete about their

persons articles of value. Also, many soldiers of the English regiments

got possession of jewelry and gold ornaments taken from the bodies of

the slain Sepoys and city inhabitants, including strings of pearls and

gold mohurs which had fallen into their hands. |

|

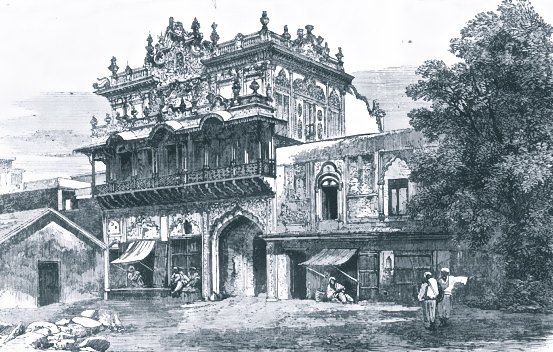

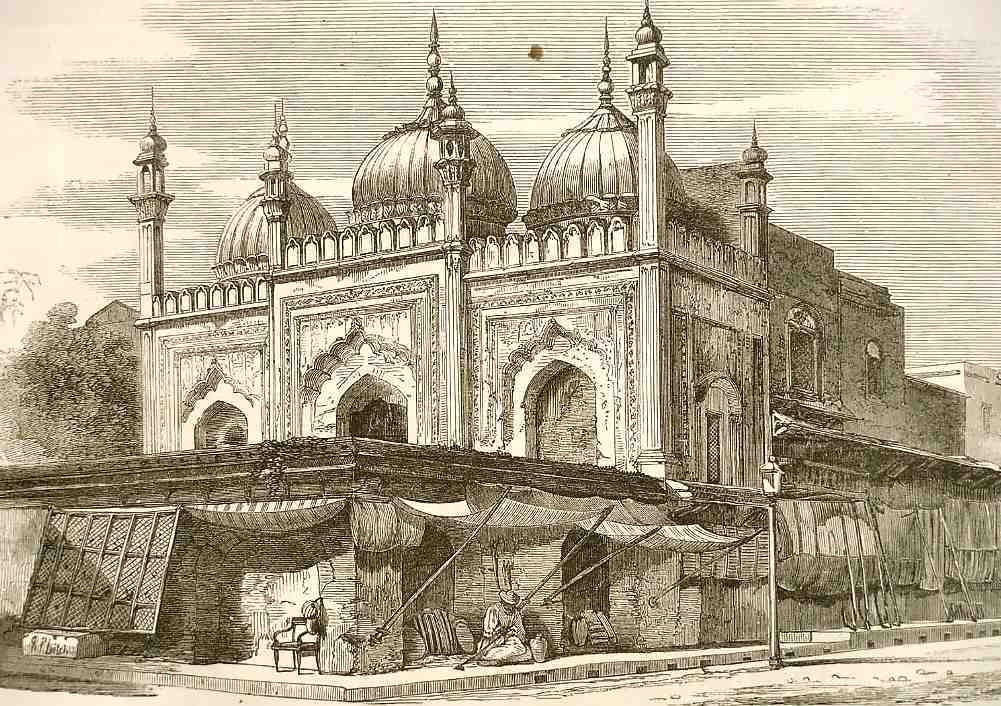

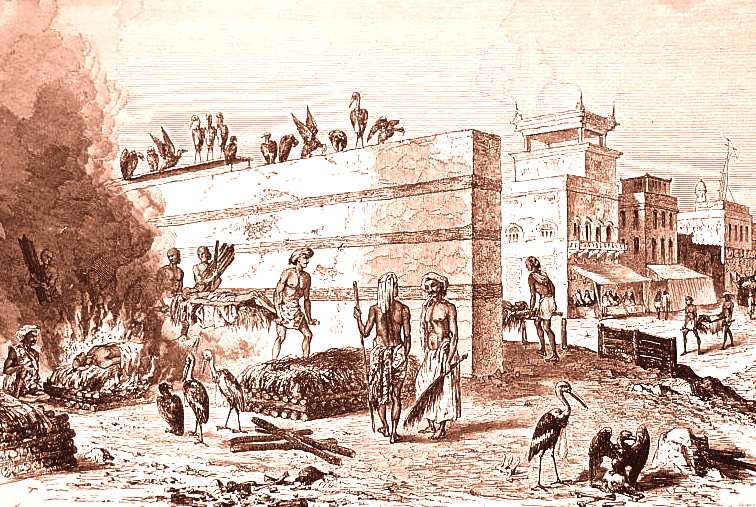

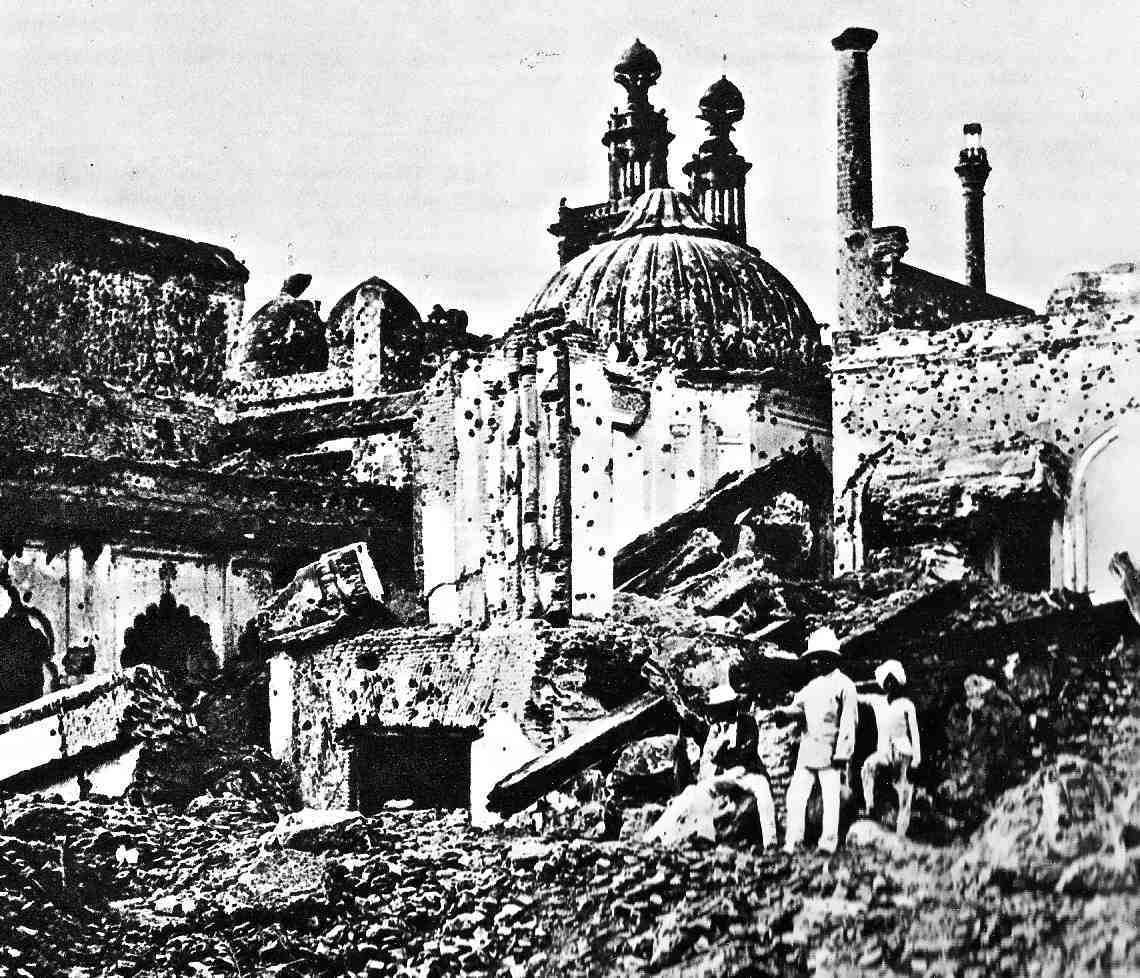

Mosque Roshun ad Dawla . . . circa

1857

Mosque Roshun ad Dawla, stands in the principal

street, and its pinnacles and domes are splendidly gilt. It is made

famous through its connection with an act of cruelty on the part of

Sheikh Nadir. This remarkable, but fearfully cruel monarch, on

conquering Delhi in the year 1739, had 100,000 of the inhabitants cut to

pieces, and is said to have sat upon a tower of this mosque to watch the

scene. The town was then set fire to and plundered. |

|

The gruesome story of the Siege of Cawnpore. On June 27th, 1857, in

Cawnpore, India, a British garrison with many women and children, under

siege, were offered safe passage and sanctuary. Instead, they were

betrayed and butchered. The surviving women and children were later

hacked to death. Retribution, when it came, was unrelentingly severe.

|

|

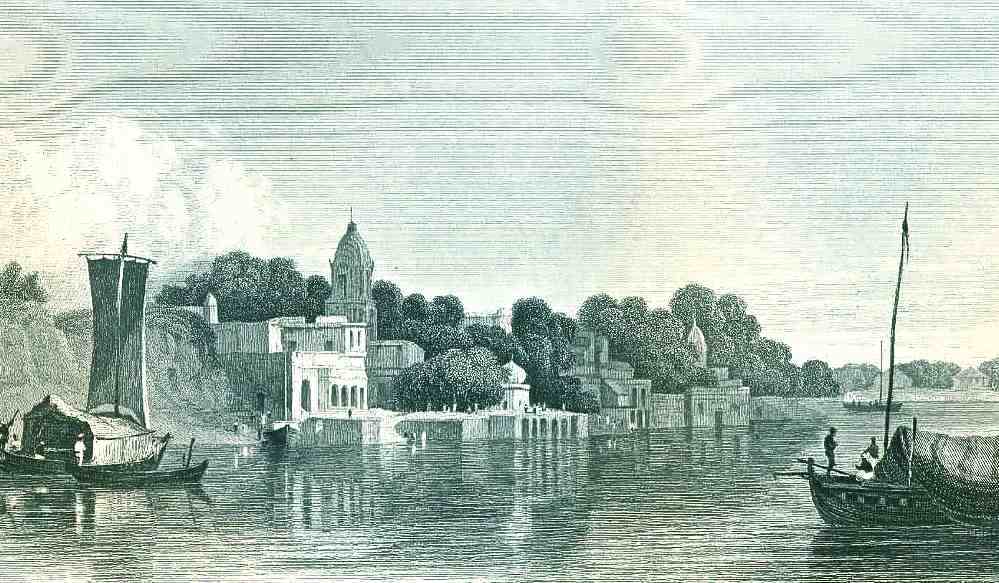

Cawnpore on the River Ganges |

| Cawnpore (modern Kanpur) is situated on the west side of the Ganges,

which is here more than a mile broad, and is crossed by a bridge of

boats. Cawnpore was in 1857 a major crossing point on the Ganges River,

and an important junction, where the Grand Trunk Road and the road from

Jhansi to Lucknow crossed.

Cawnpore became a vitally important garrison town, straddling key

communication lines. It lay on the approaches to the Punjab, Sind and

the newly acquired Oudh provinces. During a long series of years

Cawnpore had been one of the most important military stations in India.

There were few officers either of the Queen's or the East India

Company's Army who, during the period of their Eastern service, had not,

at some time or other, done duty in that vast cantonment. Unfortunately,

new conquests had denuded the encampment of many of its European

soldiers. It was thought that they were needed to help pacify the newly

acquired areas.

The Cawnpore Division was then commanded by General Sir Hugh Wheeler.

He was an old and a distinguished officer of the East India Company's

Army. He had seen much good service in Afghanistan and in the Punjab,

and had won his spurs under Gough in the second Sikh War. He had then

been in command of a division of Gough’s army. His fine military record

gave the Europeans in the area a reason to feel confident that the

mutiny might pass them by. Other than the East India Officers, the

European contingent was a strange collection of military families,

business owners, barbers, operators of toll roads, telegraphs and

railway engineers.

The station at Cawnpore was a large, straggling place, six or seven

miles in extent. There was nothing peculiar to Cawnpore in the fact that

the private dwelling houses and public offices of the English were

scattered about in the most random manner, as though they had fallen

from the sky. At the north-western extremity, lying between the road to

Bithii and the road to Dehli, were the principal houses of the

civilians, the Treasury, the Jail, and the Mission premises. These

buildings lay beyond the lines of the military cantonment, in the

extreme north-western corner of which, was the Magazine. In the centre,

between the city and the river, were the Church, the Theatre, the

Telegraph office, and other public edifices, whilst scattered about here

and there, without any apparent system, were the principal military

buildings, European and Native. The Native lines lying for the most part

in the rear towards the south-eastern point of the cantonment.

|

|

Cawnpore Street Scene . . . circa

1857 |

The city of Cawnpore had nothing in or about it to make it famous.

It had no venerable traditions, no ancient historical remains, or

architectural attractions, to enable it to rank with Banaras or Agra.

Commercially, it shone only as the city of workers-in-leather. It was a

great emporium for harness of all kinds, and for boots and shoes alike

of the Asiatic and the European types of civilization. If not better,

these articles were cheaper than elsewhere, and few English officers

passed through the place without supplying themselves with leather-ware.

But life and motion were never wanting to the place, especially on the

river-side, where many stirring signs of mercantile activity were ever

to be seen. The broad waters of the Ganges floated vessels of all sizes

and all shapes, some clustering about the landing-steps, busy with the

debarkation of produce and goods of varied kinds. People waiting for the

ferry boats that crossed and re-crossed the Ganges, were a motley

assemblage of different nations and different callings and different

costumes, whilst a continual babel of many voices rose from the excited

crowd. In the streets of the town itself there was little to evoke

remark. But perhaps, among its sixty thousand inhabitants, there may

have been, owing to its contiguity to the borders of Oudh, rather a

greater strength than common of the "rebellious types". |

|

Cawnpore Mutiny |

| The story of the revolt at Meerut reached Sir Hugh Wheeler, and from

that date there reigned in his mind the conviction that a rising at

Cawnpore might take place at any moment. All that was needed, it then

appeared to General Wheeler, and to others, was a place of refuge, for a

little space, during the confusion that would arise on the first

outbreak of the military revolt, when, doubtless, there would be plunder

and devastation. It was felt that the Sepoys had at that time no craving

after European blood, and that their departure would enable General

Wheeler and his Europeans to march to Allahabad, taking all the

Christian people with them. |

Of all the defensible points in the Cantonment, the Magazine, in the

north-western comer of the military lines was best adapted for a

defensive position. It almost rested on the river, and it was surrounded

by walls of substantial masonry. But instead of this, Sir Hugh Wheeler

selected a spot about six miles lower down to the south-east, at some

distance from the river, and not far from the Sepoys' huts. There were

quarters of a kind for the British within two long hospital barracks

(one wholly of masonry, the other with a thatched roof). They were

single-storied buildings with verandahs running round them, and with the

usual outhouses attached. This spot General Wheeler began to entrench,

to fortify with artillery, and to provision with supplies of various

different kinds.

Wheeler pushed the fortifying and supplying of the two barracks with as

much speed as possible. The fortifications were to consist of

earthworks. But the rains had not fallen, the soil of the plain was

baked almost to the consistency of iron, and the progress was

consequently slow. Whilst laboring on these works, Sir Hugh communicated

freely with the civil authorities at the station, with Sir Henry

Lawrence at Lucknow, and with the Government at Calcutta.

Wheeler, feeling that the storm might burst at any moment, pushed on

with all his energy the preparation of the barracks. His spies told him

that every night meetings of an insurrectionary character were taking

place in the lines of the Native Sepoys. In ordinary times these

meetings would have been stopped with a high hand, but the example of

Meerut had forestalled that action. Besides, General Wheeler had but

sixty-one men to depend upon. Then, on May 21st, 1857, he received

information that the Sepoys would rise that night. He accordingly moved

all the women and children into the entrenchment, and attempted to have

the contents of the treasury conveyed thither, but the Sepoys would not

part with the money. |

General Hugh Wheeler |

|

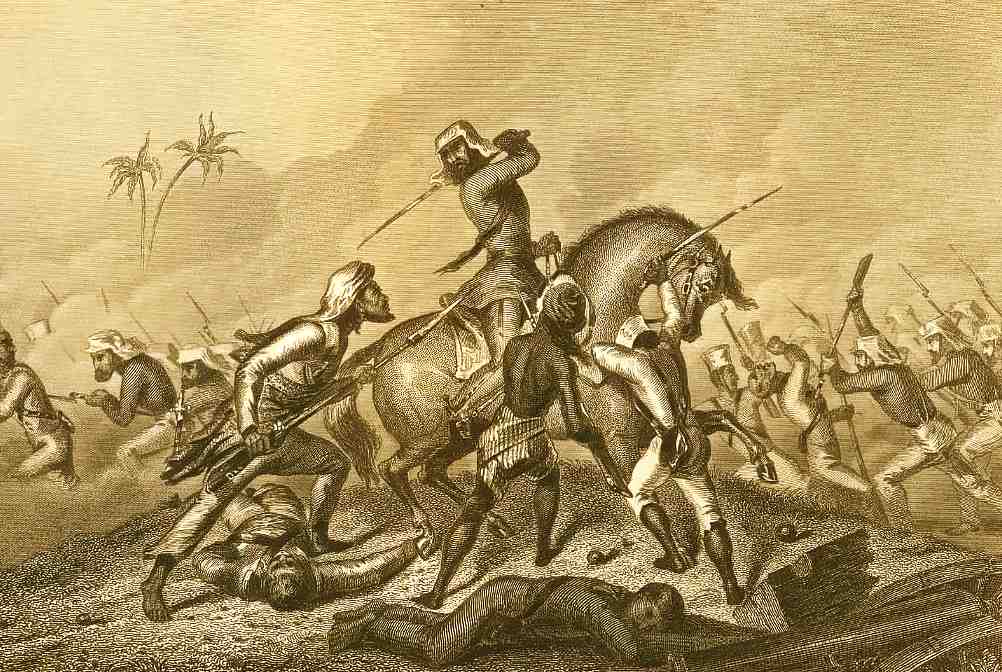

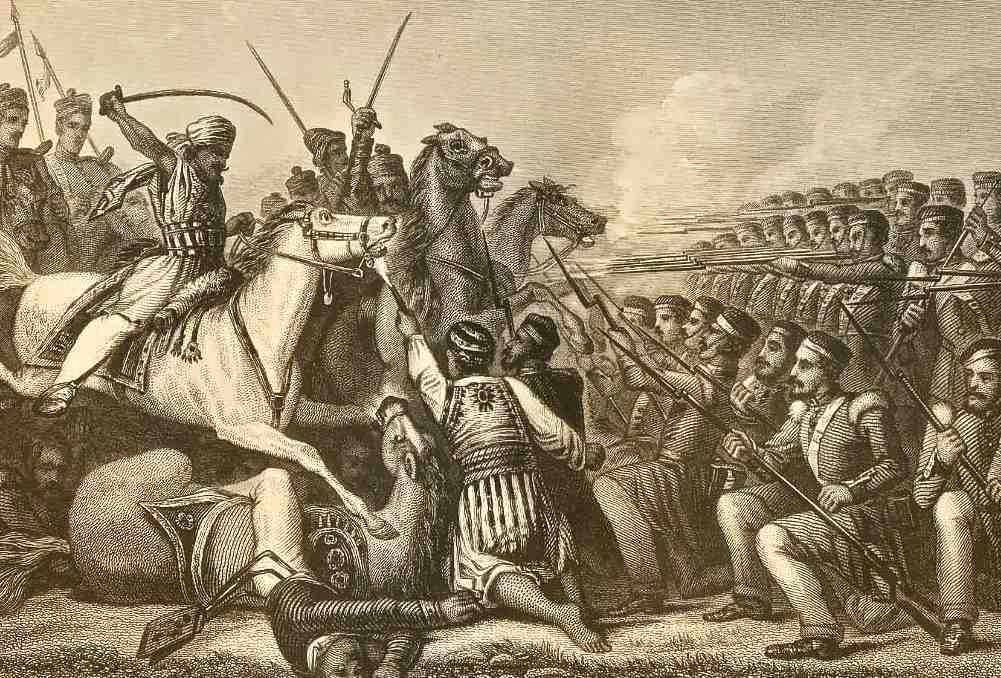

Cawnpore Battle_1857 |

| While these precautions were being taken, the General sent an

express to Lucknow requesting Sir Henry Lawrence to lend him, for a

while, a company or two of the 32nd Regiment, as he had reason to expect

an immediate rising at Cawnpore. Little could Lawrence spare a single

man from the troublous capital of Oudh. He sent all that he could send,

some eighty-four men of the 32nd, Queen's, packed closely in such

wheeled carriages as could be mustered. He sent also two detachments of

the Oudh Horse to keep open the road between Cawnpore and Agra, and

render such other assistance as Irregular Horse, well commanded, can

accomplish. A party of Oudh Artillery accompanied them with two field

guns. |

| Dondu Pant Nana Sahib, a man apparently on friendly terms with General Wheeler

and his Indian wife, promised his loyalty in the conflict due to engulf

the British. Then it was that the General, much against the grain,

availed himself of an offer made by the Nana Sahib, and agreed that 200

of the Bithur chiefs men should be posted at Nuwdbganj, guarding the

treasury and the magazine.

So when danger threatened them, it appeared to the authorities at

Cawnpore that assistance might be obtained from Nana Sahib. He had an

abundance of money and all that money could purchase, including horses

and elephants and a large body of retainers, almost, indeed, a little

army of his own. He had been in friendly association with the British up

to this very time, and no one doubted that as he had the power, also he

had the will to be of substantial use to them in the hour of their

trouble. It was one of those strange revenges, with which the stream of

time is laden.

Nana Sahib lived near Cawnpore, in the town of Bithur. Nana Sahib was

the adopted heir of the last great Mahratta King Baji Rao, who, after

defeat by the British, had been settled in luxurious exile at Bithur.

For 33 years the British paid the Prince a lavish pension, but when he

died in1851, unfortunately for Nana Sahib, the East India Company

decided that Baji Rao's pension would die with him and would not be

passed on to any successors. Nana Sahib lobbied hard sending an envoy to

London, to petition the Queen directly, but to no avail. This

dispossessed Hindu aristocrat would play a dangerous double game before

deciding who to support in the mutiny.

On May 23rd, 1857, the reinforcements from Lucknow arrived. Fletcher

Hayes, amongst the relief force, graphically described the situation in

a private letter, "I never witnessed such a scene of confusion, fright,

and bad arrangement as the European barracks presented. Four guns were

in position loaded, with artillerymen in nightcaps with sidearms on,

hanging to the guns in groups, looking like melodramatic buccaneers."

|

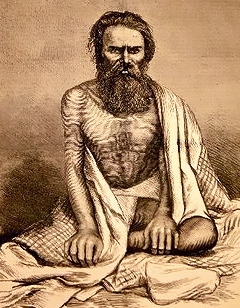

Nana Sahib |

| Hayes continued, "People of all kinds, of every color, sect, and

profession, were crowding into the barracks. Vehicles of all sorts drove

up and discharged a miscellaneous mob of every complexion, all in terror

of the imaginary foe; ladies sitting down at the rough mess-tables in

the barracks, women suckling infants, children in all directions, and

officers too!“ But during that last week of May, 1857, whatever plots

and perils might have been fermenting beneath the surface, outwardly

everything was calm and reassuring. And the brave old General began to

think that the worst was over, and that he would soon be able to assist

Sir Lawrence at Lucknow.

But everywhere in the Lines and in the Bazaars the plot was working. And

the plotters were not only there. Out at Nawabganj, where the retainers

of the Bithur were posted, were the germs of a cruel conspiracy.

During the first days of June, 1857, there were frequent meetings

between the chiefs of the rebellious Sepoys and the inmates of the

Bithur Palace. It was known to the soldiery before they broke into

rebellion that the Nana was with them, and that all his resources would

be thrown on the side of the nascent rebellion.

On the night of the June 4th, 1857, the 2nd Cavalry and the 1st

Infantry Regiment were ready for immediate action. The troopers had got

to horse and the foot soldiers were equipping themselves. As ever, the

former were the first to strike. There was a firing of pistols, with

perhaps no definite object. Then a conflagration which lit up the sky

and told the British in the entrenchments that the game of destruction

had commenced. Then, a mad nocturnal ride to Nawabganj, scenting the

treasure and the stores in the Magazine. The Regiment soon followed

them. The Sepoys did not wish to harm their officers, but they were bent

on rebellion. They hurried after the Cavalry, setting their faces

towards the north-west, where lay the Treasury, the Jail, and the

Magazine, with Dehli in the distance. As they went they burnt, and

plundered, and spread devastation along their line march, but left the

Christian people behind them, not lusting for their blood. |

|

|

Arriving in the neighborhood of Nawabganj, the Sepoys of the two

regiments fraternized with the retainers of Nana Sahib and he announced

his loyalty to the mutiny and his desire to become a Hindu vassal of the

Muslim Moghul Empire. The Treasury was

sacked, the gates of the Jail were thrown open and the prisoners

released. The public offices were fired and the records burnt. The

Magazine, with all its supplies of ammunition, and the priceless wealth

of heavy artillery, fell into the hands of the Mutineers. The spoil was

heaped upon elephants and on carts, which the troopers had brought from

their Lines; and the one thought of the soldiery was a hurried march to

the great imperial centre of the rebellion, Delhi. The remaining

regiments joined them the following morning.

It was the plan of the Cawnpore mutineers to make their way straight to

Dehli, to join the regiments already assembled there, and to serve the

cause of the King. They had money and munitions of war and carriage for

the march, and they expected great tidings from the restored sovereignty

of the Moghul Emperor.

But Nana Sahib, stimulated by those about him, and chiefly, it is

thought, by the wily Muhammadan, Azimullah, looked askance at the

proposed centralization of the rebellion, and urged upon the Sepoy

leaders that something better might be done. They had made one march

towards the imperial city, but had halted at Kalianpur, whither the Nana

had accompanied them. Then they began to listen to the voice of the

charmer, and to waver in their resolution. The Bithur people might be

right they thought. It might be better to march back to Cawnpore. |

| Wise in his generation, the Nana Sahib saw clearly the danger of an

eclipse. To march to Dehli would be to place himself in a subordinate

position, perhaps to deprive him of all substantive authority. The

troops might desert him. The Emperor might repudiate him. In the

neighborhood of Cawnpore he would be supreme master of the situation. He

knew well the weakness of the English. He knew well that at Lucknow the

danger which beset the British was such that no assistance could be

looked for from that quarter, and that none of the large towns on the

Ganges offered any prospect of immediate relief. With four disciplined

Native regiments and all his Bithur retainers at his back, with guns and

great stores of ammunition and treasure in abundance, what might he not

do? At Kalianpur, therefore, the Nana arrested the march of the

mutineers to Dehli. It is not very clearly known what arguments and

persuasions were used by him or his ministers to induce the mutinous

regiments to turn back to Cawnpore. It is probable that they were

induced by promises of large gain.

Ominously for the British, the mutineers trundled back into town. This

time, they made sure that they had expunged all the Europeans from

outside of the entrenchment and systematically plundered and destroyed

all European owned property. Native Christians were also singled out for

gruesome fates. Whilst all this was happening Nana Sahib took the time

to write a letter to General Wheeler informing him to expect an attack

the next morning.

Only a few days before the regiments had broken into rebellion, Nana

Sahib had been in friendly and familiar intercourse with English

officers, veiling his hatred under the suavity of his manners and the

levity of his speech. But as day dawned on Saturday, the 6th of June,

Wheeler was startled by the receipt of a letter from Nana Sahib,

intimating that he was about to attack the entrenchments. There was not

an hour to be lost. Forth went the mandate for all the English to

concentrate themselves within the entrenchments. |

|

|

|

|

Barracks Entrenchments |

| At 10:30 am on June 6th 1857, the rebel artillery opened up a

prolonged barrage signaling the start of the siege. The defenders could

not make an effective reply due to their smaller guns and the need to

keep canister shot loaded in case of a sudden charge. The siege of

Cawnpore was not a protracted affair. It lasted just over three weeks,

but it took place in June when the Indian sun is at its most merciless.

The June sky was little less than a great canopy of fire. The summer

breeze was as the blast of a furnace. To touch the barrel of a gun was

to recoil as from red-hot iron. Even under the fierce meridian sun, this

little band of English fighting men were ever straining to sustain the

strenuous activity of constant battle against fearful odds.

The Mutineers had an immense wealth of artillery. The Cawnpore Magazine

had sent forth vast supplies of guns and ammunition. And now the heavy

ordnance of the Government was raking the British with a destructiveness

which soon diminished the numbers working in the trenches. The English

artillerymen dropped at their guns, until one after another the places

of the trained gunners were filled by volunteers and amateurs, with

stout hearts but untutored eyes, and the lighter metal of their guns

could make no adequate response to the heavy fire of the Mutineers’

twenty-four pounders. |

Many in the entrenchments, not bred to arms, started suddenly into

stalwart soldiers. Among them were some railway engineers, potent to do

and strong to endure, who flung themselves into the work of the defense,

and made manifest to their assailants that they were men of the warrior

caste, although they wore no uniforms on their backs. Conspicuous among

them was Mr. Ileberden, who was riddled with grape-shot, and lay for

many days, face downwards, in extreme agony, which he bore with

unremitting fortitude until death came to his relief.

After the siege had lasted about a week a great calamity befell the

garrison. In the two barracks gathered together all the feeble and

infirm, the old and the sick, the women and the children. One of the

buildings had a thatched roof, and, whilst all sorts of projectiles and

combustibles were flying about, its ignition could be only a question of

time. Every effort had been made to cover the thatch with loose tiles or

bricks, but the" protection thus afforded was insufficient, and one

evening the whole building was in a blaze. The scene that ensued was one

of the most terrible in the entire history of the siege, for the sick

and wounded who lay there, too feeble and helpless to save themselves,

were in peril of being burnt to death. To their comrades it was a work

of danger and difficulty to rescue them, for the Mutineers, rejoicing in

their success, poured shot and shell in a continuous stream upon the

burning pile, which guided their fire through the darkness of the night.

The destruction of the barrack was a heavy blow to the besieged. It

deprived numbers of women and children of all shelter, and sent them out

houseless to lay day after day and night after night upon the bare

ground, without more shelter than could be afforded by strips of canvas

and scraps of wine-chests, feeble defenses against the climate, which

were soon destroyed by the unceasing fire of the enemy. |

|

| There was another result of this conflagration. The few faithful

Sepoys who cast in their lot with their English officers, and

accompanied them within the entrenchments, had been told to find shelter

in this barrack. The 53rd Regiment sent ten Native officers, with

faithful Sepoys, into General Wheeler's camp. All the other regiments

contributed their quota to the garrison, and there is evidence that

during the first week of the siege they rendered good service to the

English. But, when the barrack was destroyed, there was no place for

them. Provisions were already falling short, and, although there was no

reason to mistrust, it was felt that they were rather an encumbrance

than an assistance. So they were told that they might depart. Although

there was danger beyond the entrenchments, there was greater danger

within them, and they not reluctantly perhaps turned their faces towards

their homes.

The General's son and aide-de-camp, Lieutenant Wheeler, was lying

wounded in one of the barrack-rooms, when, in the presence of his whole

family, father, mother, and sisters, a round shot boomed into the

apartment, and carried off the young soldier's head!

There was a well a little way outside the entrenchments, which served

as the general cemetery of the Christian people, and night after night

the carnage of the day was carried to this universal mausoleum. And

there were some who died hopelessly, though not in the flesh, for the

horrors of the siege were greater than they could bear, and madness fell

upon them, perhaps as a merciful dispensation. It is known that in the

space of three weeks the English consigned to the well two hundred and

fifty of their party. The number of bodies buried by the insurgents, or

devoured by the vultures and jackals, must have been at this amount many

times told. If hands were scarce in the entrenchments, muskets were not,

and every man stood to his work with some spare pieces ready-loaded,

which he fired with rapidity.

It was the centenary of the Battle of Plassey (June 23rd, 1757). On

the previous night there had been signs of extraordinary activity in the

enemy's ranks, and a meditated attack on the outposts had been thwarted.

As the morning of the 23rd dawned upon Cawnpore, the insurgents,

stimulated to the utmost by the associations of the day (legend called

for the defeat of the British 100 years after Plassey), came out in full

force of Horse, Foot, and Artillery, flushed with the thought of certain

success, determined to attack both outposts and entrenchments.

There was a stern resolution, in many cases strengthened by oaths on the

Ganges-water or the Koran, to destroy the English or to die in the

attempt. The excitement of all branches of the rebel-army was at its

highest pitch. The impetuosity of the Cavalry far exceeded their

discretion, for they galloped forward furiously within reach of the

British guns, and met with such a reception, that many horses were left

rider-less, and the troopers who escaped wheeled round and fled in

confusion. The Infantry, more cautious, improvised moving ramparts to

shelter their movement. They advanced huge bales of cotton, but the

British guns were too well served to suffer this device to be of much

use to the enemy, for some well-directed shots from the batteries set

fire to these defenses, and the assault was defeated. |

Nana Sahib |

The attack on the outer barracks was equally unsuccessful. The enemy

swarmed beneath the defense walls, but were saluted with so hot a fire

that, in a little time, the seventeen defenders had laid one more than

their number dead at the doorway of the barrack.

But there was a more deadly foe than this enemy mass of Hindus and

Muhammadans to be encountered. The Nana Sahib perceived another source

of victory than that which lay in the number of his fighting men. For

hunger had begun to gnaw our little garrison. Food, which in happier

times would have been turned from with disgust, was seized with avidity

and devoured with relish. To the flesh-pots of the besieged no carrion

was unwelcome. A stray dog was turned into soup. An old horse, fit only

for the knackers, was converted into savory meat. And when glorious good

fortune brought a Brahmani Bull within the fire of the defenses, and

with difficulty the carcass of the animal was hauled into the

entrenchments, there was rejoicing as if a victory had been gained. But

in that fiery month of June the agonies of thirst were even greater than

the pangs of hunger. The well from which scant supplies of water were

drawn was a favorite mark for the Sepoy gunners. It was a service of

death to go to and fro with the bags and buckets which brought the

priceless moisture to the lips of the famished people. Strong men and

patient women thirsted in silence, but the moans of the wounded and the

wailings of the children was pitiable to hear. And so as day by day the

English people were wasting under these dire pangs of hunger and thirst,

the hopes of the Nana Sahib grew higher and higher, and he knew that the

end was approaching. |

Three weeks had now nearly passed away since the investment had

commenced. No further reinforcements had come to their assistance. Their

numbers were fearfully reduced. Their guns were becoming unserviceable.

Their ammunition was nearly expended, and starvation was staring them in

the face. To hold their position much longer was impossible. To cut

their way out of it, with all those women and children, was equally

impossible.

When thus, as it were at the last, there came to them a message from the

Nana Sahib, brought by the hands of a Christian woman. It was on a slip

of paper in the handwriting of Azimullah, and it was addressed "To the

subjects of Her Most Gracious Majesty Queen Victoria, all those who are

in no way connected with the acts of Lord Dalhousie, and are willing to

lay down their arms, shall receive a safe passage to Allahabad."

When they thought of the women and children, and of what might befall if

the overtures of Nana Sahib were rejected, the messenger carried back to

the enemy's camp an announcement that General Wheeler and his chief

officers were deliberating upon the offer that had been made to them.

Next morning (there was then an armistice), Azimullah and Jawala-l

arshad, presented themselves near the entrenchments, and Captain Moore

and others went out with power to treat with the emissaries of the Nana.

It was then proposed that the British should surrender their fortified

position, their guns, and their treasure, and that they should march out

with their arms and sixty rounds of ammunition in each man's pouch. On

his part, the Nana was to afford them safe conduct to the river side,

and sufficient carriage for the conveyance of the women and the

children, the wounded and the sick. Boats were to be in readiness at the

ghaut (flight of steps leading down to a river) to carry them down the

Ganges, and supplies of flour, sheep and goats also were to be laid in

for the sustenance of the party during the voyage to Allahabad.

These proposals were committed to paper and given to Azimullah, who laid

them before his chief, and that afternoon a horseman from the rebel camp

brought them back, saying that the Nana Sahib had agreed to them. |

|

|

|

|

|

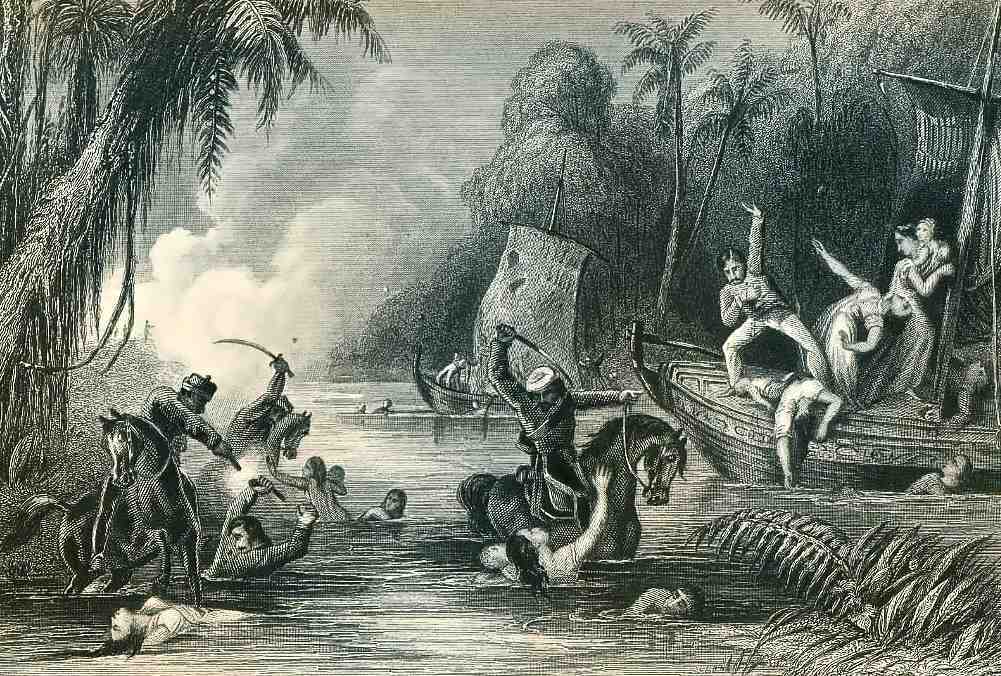

| On June 27th, 1857, from their entrenchments, in the early morning,

went the remnant of the garrison, with the women and the children, who

had outlived the horrors of the siege. They wore gaunt and tattered

garments, were emaciated and enfeebled by want, worn by suffering, some

wounded and scarred with the indelible marks of the battle upon them.

The river was distant only a mile from the defenses, but to them it was

a long journey. The wounded were carried mostly in palanquins. The women

and children went in rough native bullock carriages or on the backs of

elephants, whilst the able-bodied marched out on foot with but little

semblance of initial array. General Wheeler, with his wife and

daughters, are said to have walked down to the boats.

The place of embarkation was known as the Sati Chuara Ghaut, so

called from a ruined village near by which bore that name. The road ran

across a wooden bridge. Over this bridge they filed down into a ravine,

which led on to the river-side. Near the ghaut was a Hindu temple, known

as the Temple of Hardeo, or the Fisherman's Temple, a structure of

somewhat fanciful and picturesque design. The incidents of this

mile-march were not many.

At the place of embarkation, the uncouth vessels were seen a little way

off in the stream in shallow water, for it was the close of the dry

season and the river was at its lowest. The boats were the ordinary

eight-oared budgerows of the country. They were ungainly structures with

thatched roofs, looking at a distance like floating hay-stacks, and into

these the people began to crowd without order or method, even the women

with children in their arms, with but little help from others, wading

knee-deep in the water, and scrambling as they best could up the sides

of the vessels. It was nine o'clock before the whole were aboard the

vessels.

So foul an act of treachery was prepared by Dondu Pant Nana Sahib. The adopted son of the last of the Peshwa had studied to some purpose

the early history of his race. He knew how the founder of the Maratha

Empire, the head of the great family who had been the masters of the

Peshwas had, under false pretext of friendly embrace, dug his Vaknak

into the bowels of a Muhammadan envoy, and gained by foulest treachery

what he could not gain by force. The Vaknak was now ready - "Vaknak of a

Thousand Claws" in the hands of the man who aspired to be the founder of

a new or renovated Maratha Empire. ["Valcnak" or "Vagnak", is a weapon

made of five rings, to each of which is attached a steel claw, like that

of a tiger. The rings fit the fingers of the hand, and the claws lie

concealed in the palm, till the moment for striking arrives] |

|

|

Everything was ready for the great carnage. Tantia Topi, who had

been appointed master of the ceremonies, sat enthroned on a "Chabutra"

or platform, of a Hindu temple, and issued his orders to his dependants.

Azimullah, also was there, and the brethren of the Nana Sahib, and Tika

Singh, the new Cavalry General, and others of the-leading men of the

Bithur party. And many Zemindars from the districts, and merchants and

lesser people from the city, are said to have gone forth and to have

lined the river banks to see the exodus of the English. Not knowing what

was to come. It looked like a great holiday show.

No sooner were the English people on board the boats, than the foul

design became apparent. The sound of a bugle was heard. The Native

boatmen clambered over the sides of the vessels and sought the shore.

Then a murderous fire of grapeshot and musket-balls was opened upon the

wretched passengers from both banks of the river, and presently the

thatch of the bugerows, cunningly ignited by hut cinders, burst into a

blaze. There was then only a choice of deaths for the Christians. The

men, or the foremost amongst them, strenuous in action to the last,

leaped overboard, and strove, with shoulders to the hulls of the boats,

to push them into mid-channel. But the bulk of the fleet remained

immovable, and the conflagration was spreading. The sick and wounded

were burnt to death, or more mercifully suffocated by the smoke, while

the stronger women, with children in their arms, took to the river to be

shot down in the water, to be sabre'd in the stream by the mounted

troopers who rode in after them, to be bayoneted on reaching land, or to

be made captives and reserved for a later and more cruel immolation.

While this terrible scene was being acted at the ghaut, the Nana

Sahib, having full faith in the malevolent activity of his lieutenants

on the riverbank, was awaiting the issue in his tent on the cantonment

plain. It is related of him that, unquiet in mind, he moved about,

pacing hither and thither, in spite of the indolence of his habits and

the obesity of his frame. After a while, tidings of the progress of the

massacre were brought to him by a mounted trooper. What had been passing

within him during those morning hours no can know. Perhaps some slight

spasm of remorse may have come upon him, or he may have thought that

better use might be made of some of British alive than dead. But,

whether moved by pity or by craft, he sent orders back by the messenger

that no more women and children should be slain, but that not an

Englishman was to be left alive. So the Mutineers, stayed their hands

and ceased from the slaughter. Probably one hundred and twenty-five half

drowned, all dripping with the water of the Ganges and begrimed with its

mud, were carried back in custody to Cawnpore, by the way they had come.

The hunting down of fleeing survivors occupied several days. All who had

not been burnt, bayoneted, sabre’d, or drowned in the great massacre of

the boats on the 27th of June, had been swept up and carried to the

Savada House. A building which had figured in the history of the siege.

For a time, it had been the head-quarters of the rebel leader. And now

these newly-made widows and orphans were added to the shuddering herd of

condemned innocents. Eighty was their number. They were brought back on

carts, and arrived on June 30th, 1857.

Delafosse, with privates Murphy and Sullivan, alone survived to reach

the territory of a friendly Eajah, and lived to tell the story of

Cawnpore. |

|

|

| The Nana Sahib, carrying with him an infinite satisfaction derived

from the success of his machinations, went off to his palace at Bithur.

Next day, in all the pride and pomp of power, he was publicly proclaimed

Peshwa. No formality, no ceremony was omitted, that could give dignity

to the occasion. He took his seat upon the throne. The sacrament of the

forehead-mark was duly performed. The cannon roared out its recognition

of the new ruler. And when night fell the darkness was dispersed by a

general illumination, and showers of fireworks lit up the sky. |

| But it was not long before, even in the first flush of triumph,

heaviness fell upon the restored sovereignty of the Peshwa. And news

soon reached Nana Sahib that in his absence from Cawnpore, his influence

was declining. The Muhammadan party was waxing strong. It had hitherto

been overborne by the Hindu power, probably more than all else for want

of an efficient leader. But there was a Muhammadan nobleman, known as

the Nani Nawab, who had taken a conspicuous, if not an active, part in

the siege. At the commencement of the outbreak he had been made prisoner

by the Nana Sahib, and his house had been plundered, but subsequently

they had entered into a covenant of friendship. He directed or presided

over one of the batteries planted at the Eacquet Court, daily driving

down to it in his carriage and sitting on a chair, in costly attire,

with a sword at his side and a telescope in his hand. There was no

battery that wrought the British greater mischief than Nani Nawab's.

Nana Nawab had got together some cunning Native artificers, who

experimented with red-hot shot and other combustibles, not without

damage to the lives of those working in the batteries. It was a

projectile from one of his guns, described as a ball of resin, which set

fire to the barrack in the entrenchments. Among the Muhammadans of the

neighborhood he was held in high estimation, and large numbers of

followers attended him as he went down every day to his battery.

And now there was some talk of setting up the Nawab as head of the new

Government. If this had been done, there would have been faction fights

between Hindus and Muhammadans.

Then other disturbing rumors reached him. The English reinforcements

were advancing from Allahabad, hot for revenge, eager for blood. The

story ran that the British soldiers were hanging every Native who came

in their way. A great fear was settling down upon the minds of the

inhabitants of Cawnpore. |

|

After the fashion of the East, he strove to drown his cares and

anxieties with music, and dancing, and stately appearances in public,

and he solaced himself in more retired hours, with strong drink and the

caresses of a famous courtesan.

But ever, as the month of July wore on, news came that the English were

advancing, and the Peshwa trembled as he heard, even in the midst of his

revelries. There was however, one more victory to be gained before the

collapse of the new Maratha power on the banks of the Ganges. And the

Nana Sahib smiled, as he thought that the game was all in his own hands. |

|

There was one remarkable escape

story that may have had a kernel of truth to it. As the Sati Chaura

massacre took place, a Sowar rode off with one of General Wheeler's

daughters slung over his saddle. It was believed (or rather hoped) that

she had slain her captor before he had his wicked way with her. This is

what this picture shows. However, the truth may have been that she was

indeed rescued by a Sowar named Ali Khan. Some fifty years later an old

lady in Cawnpore on her deathbed confessed to a Catholic Priest that she

was the daughter of General Wheeler. Perhaps she had been too

embarrassed or perhaps genuinely felt for the safety of her captor.

Needless to say, this image shows the Victorian ideals of a lady who

would choose death before dishonor. |

The prisoners bad been removed from the Savada Koti to a small

house, which had been built by an English officer for his native

mistress, but had more recently been the residence of a humble Eurasian

clerk. There was scanty accommodation in it for a single family. In this

wretched building were now penned, like sheep for the slaughter, more

than two hundred women and children. For the number of the captives had

by this time been increased by an addition from a distance. This new

prison-house lay between the Native city and the river, under the shadow

of the improvised palace of the Peshwa, within sound of the noisy music,

and within sight of the torch glare.

A great body of cavalry and infantry soldiers, with a formidable array

of guns, had gone down to dispute the progress of the British, but

before the month of July was half spent, news came that they had been

disastrously beaten. Havelock had taken the field in earnest. |

Assured of the fact that Cawnpore had fallen, General Havelock was

eager to advance. On July 7th, 1857, he gave the order to march. It was

but a small force for the work before it. A thousand European Infantry

soldiers, belonging to four different regiments, composed the bulk of

Havelock's army. Some of these were seasoned soldiers, but some were raw

recruits. Then there were a hundred and thirty of Brazier's Sikhs, a

battery of six guns, and a little troop of Volunteer Cavalry.

Havelock marched forth for the recovery of Cawnpore and the relief of

Lucknow. It was a dull, dreary afternoon when Havelock's Brigade marched

out of Allahabad, and very soon the rain came down in torrents to damp

the spirits of the advancing force. As Havelock advanced, it became more

and more apparent to him not only that Cawnpore had fallen, but that a

large body of the enemy were advancing to meet him.

July 12th about seven o'clock the whole force halted at Balindah, a spot

some four miles from the city of Fathpur. A rebel force came on

menacingly in an extended line, as though eager to enclose what they

thought was a small force. The weak detachment that was to have been so

easily overwhelmed, had suddenly grown, as though under the hand of

“Shiva the Destroyer”, into a strong, well-equipped, well-handled force

of all arms, advancing to the battle with a formidable line of guns in

the centre. Eager for fresh slaughter, these cavalry of the Nana Sahib

had rushed upon their prey only to find themselves brought face to face

with death. The fight commenced. The British Enfield Rifles and cannon

would not permit a conflict. The service of the Artillery was superb.

The best troops of the Nana Sahib, with a strength of Artillery

exceeding the English, could make no stand against such a fire as was

opened upon them. The Mutineers were falling back upon the town, with

its many enclosures. “The enemy's fire scarcely touched us," wrote

Havelock, “Our fight was fought neither with musket nor bayonet or

saber, but with long range Enfield Rifles and cannon.” |

General Henry Havelock |

On the 15th of July, Havelock came in front of the enemy. They had

posted themselves in strength at the village of Aong, with something of

an entrenchment in front, and on either flank some walled gardens,

thickly studded with trees, which afforded serviceable shelter to their

musketeers. But no superiority of numbers or of position could enable

them to sustain the attack of the English. The cost of that morning's

success was indeed heavy, and the day's work was not then over. A few

miles beyond the village of Aong was a river to be crossed, known as the

Pandu Nadi. It was but a streamlet in comparison with the Ganges, into

which it flowed. But the July rains had already rendered it swollen and

turbid, and if the bridge by which it was crossed had been destroyed,

General Havelock's progress would have been most disastrously retarded.

When Havelock's scouts told him that the enemy were rallying, and were

about to blow up the bridge, he roused his men, exhausted as they were.

It was a two hours' march to the bridge-head under a fierce sun. The

enemy, strengthened by reinforcements which had come in fresh from

Cawnpore, under Bala Rao, the brother of the Nana Sahib, were entrenched

on the other side with heavy guns, which raked the bridge. But Maude's

battery was soon brought into action, and a favorable bend of the river

enabling him so to plant his guns as to take the enemy in flank, he

poured such a stream of Shrapnel into them that they were bewildered.

They had undermined the bridgehead, and had hoped to blow the whole

structure into the air before the English could cross the river. But the

Fusiliers, under Major Stephenson, swept across the bridge, and put an

end to all fear of its destruction. Then the rest of Havelock's force

accomplished the passage of the river, and pushed on towards Cawnpore.

They did not then know the worst. The great tragedy of Cawnpore was yet

to come. On the afternoon of that l5th of July, Nana Sahib, learnt that

Havelock's army had crossed the Pandu Nadi, and was in full march upon

his capital. The messenger who brought the evil tidings was Bala Rao

himself, with a wound in his shoulder, as proof that he had done his

best. What now was to be done? The chief advisers of the Nana Sahib were

divided in opinion. They might make a stand at Bithur, or form a

junction with the rebel force at Fathgarh, or go out to meet the enemy

on the road to Cawnpore. The last course, after much discussion, was

adopted, and arrangements were made to dispute Havelock's advance. |

|

Massacre at Cawnpore - July 15th,

1857 |

| The order went forth for the massacre of the women and children in

the Bibighur. The helpless victims huddled together in those narrow

rooms were to be killed. There were four or five men among the captives.

These were brought forth and killed in the presence of the Nana Sahib.

Then a party of Sepoys was instructed to shoot the women and children

through the doors and windows of their prison house. The task was too

hideous for their performance. They fired at the ceilings of the

chambers. The work of death, therefore, proceeded slowly, if at all. So

some butchers were summoned from the bazaars. They were stout Muslims

accustomed to slaughter, and two or three others, Hindus, from the

villages or from the Nana's guard, were also appointed executioners.

They went in, with swords or long knives, among the women and children,

as among a flock of sheep, and with no more compunction, slashed them to

death with the sharp steel. |

| And there the bodies lay, some only half dead, all through the

night. It was significantly related that the shrieks ceased, but not the

groans. Next morning the dead and the dying were brought out, ghastly

with their still gaping wounds, and thrown into an adjacent well. Some

of the children were alive, almost unhurt, saved doubtless, by their low

stature, amidst the closely-packed masses of human flesh through which

the butchers had drawn their blades, and now they were running about

scared and wonder struck, beside the well. To toss these infantile

enemies, alive or dead, into the improvised cemetery, already nearly

choked-full, was a small matter that concerned but little those who did

the Nana's bidding. None were mutilated, none were dishonored. There was

nothing needed to aggravate the naked horror of the fact that some three

hundred Christian women and children were hacked to death in the course

of a few hours. Then, this feat accomplished, the Nana Sahib and

allies prepared to make their last stand for the defense of Cawnpore and

the Peshwaship. |

|

| On the morning of July 16th, 1857, Nana Sahib went out himself with

some five thousand men, cavalry, infantry, and artillery to dispute

Havelock's advance. The position, some little distance to the south of

Cawnpore, which he took up was well selected, and all through that July

morning his lieutenants were disposing their troops and planting their

guns.

Meanwhile, General Havelock and his men, unconscious of the great

tragedy that, a few hours before, had been acted out to its close, were

pushing on, under a burning sun, the fiercest that had yet shone upon

their march. The hour of noon had passed before the English General

learnt the true position of the enemy. It was plain that there was some

military skill in the rebel camp, for the troops of the Nana Sahib were

disposed in a manner which taxed all the power of the British Commander,

who had been studying the art of war all his life. To Havelock's column

advancing along the great high road from Allahabad, to the point where

it diverges into two broad thoroughfares, on the right to the Cawnpore

cantonment and on the left, the "Great Trunk," to Dehli, the Sepoy

forces presented a formidable front. It was drawn up in the form of an

arc, bisecting these two roads. Its left, almost resting on the Ganges,

had the advantage of some sloping ground, on which heavy guns were

posted, while its right was strengthened by a walled village with a

great grove of mango-trees, which afforded excellent shelter to the

rebels. Here also heavy guns were posted. And on both sides were large

masses of Infantry, with the 2nd Cavalry in the rear, towards the left

centre, for it was thought that Havelock would advance along the Great

Trunk Road.

Havelock's former victories had been gained mainly by the far

reaching power of the Enfield Rifles and the unerring precision of

Maude's guns. But now he had to summon to his aid those lessons of

warfare, both its rules and its exceptions, which he had been learning

from his youth upwards. The order was given for the advance, and primed

with good libations of malt liquor, they moved forward in column of

subdivisions, the Fusiliers in front, along the high road, until they

reached the point of divergence. Then the Volunteer Cavalry were ordered

to move right on, so as to engage the attention of the enemy and

simulate the advance of the entire force, while the Infantry and the

guns, favored by the well wooded country moved off unseen to the right.

The feint succeeded admirably at first. The Cavalry drew upon themselves

the enemy's fire. But presently an open space between the trees revealed

Havelock's designs, and the Nana's guns opened upon the advancing

columns, raking the Highlanders and 64th, not without disastrous effect.

But nothing shook the steadiness of the advance. The last subdivision

having emerged from the wood, they were rapidly wheeled into line, moved

forward with a resolute front and disconcerted the arrangements on which

the Nana had prided himself so much and so confidently relied. But the

native legions had strong faith in the efficacy of their guns, which

outmatched the English own in number and in weight of metal. |

|

Battle of Cawnpore, India - July

16th, 1857 |

| Maude's battery was struggling through ploughed fields, and his

draft-cattle were sinking exhausted by the way, and even when they came

up, these light field-pieces, could but make slight impression on the

heavy ordnance from the Cawnpore magazine. For a little space therefore,

the Sepoys exulted in the preponderance of their artillery fire, and

between the boomings of the guns were heard the joyous sounds of

military bands, striking up stirring British national tunes, as taught

by English bandmasters, in mockery. The Sepoys selecting those with the

greatest depth of English sentiment in them. |

The awful work of charging heavy guns well served by experienced

gunners, was now to be commenced, and the Highlanders, led by Colonel

Hamilton, were the first to charge. The shrill sounds from the bagpipes

in the rear sent them all forward with a rush, and the kilted soldiers,

with their fixed bayonets, cheered as they went. Strongly posted as the

guns were in a walled village, village and guns were soon carried, and

there was an end to the strength of the enemy's left.

The Sepoy troops fled in confusion, some along the Cawmpore road, others

towards the centre of their position, where a heavy howitzer was posted,

behind which for a while they rallied. The Highlanders, followed by the

64th, flung themselves on the trenchant howitzer and the village which

enclosed it. The gun was captured, and the village was cleared.

Meanwhile, the Infantry swept on to the enemy's right, where two more

guns were posted, and carried them. But the enemy, having found fresh

shelter in a wooded village, rallied with some show of vigor, and poured

a heavy fire into the English line. The Highlanders bounded forward to

take the village. Again the Sepoy host were swept out of their cover,

and seemed to be in full retreat upon Cawnpore, as though the day were

quite lost.

But there was yet one more stand to be made. As gun after gun was

captured by the rush of the British infantry, still it seemed ever more

Sepoy guns were in reserve, to deal out death in the English ranks.

Baffled and beaten as he was, Nana Sahib was resolute to make one more

stand. He had a twenty-four pounder and two smaller guns planted upon

the road to the Cawnpore cantonment, from which fresh troops had come

pouring in to give new strength to the rebel defense. It was the very

crisis of the Peshwa state. Conscious of this, Nana Sahib threw all his

individual energies into the work before him, and tried what personal

encouragement could do to stimulate his troops. He flashed his presence

on his people in a last convulsion of courage and a last effort of

resistance. |

Scottish Highlanders |

The British bivouacked at nightfall two miles from Cawnpore, every

man weary and too thirsty not to relish even a draught of dirty water.

Next morning they marched on to occupy the city. Havelock's spies had

brought in word that the captive women and children, whom they had hoped

to rescue, had been murdered. The morning's news clouded the joy of

yesterday's victory.

The enemy had evacuated the place, leaving behind them only a body of

cavalry to announce the exodus of the rebel force by blowing up the

great magazine, the resources of which had constituted their strength,

and given them six weeks of victory. As the advanced guard neared the

Cawnpore cantonment, there was seen to rise from the earth an immense

balloon-shaped cloud, and presently was heard a terrific explosion,

which seemed to rend the ground beneath one's feet with the force of a

gigantic earthquake. The Mutineers had detonated the magazine!The

once boastful army of the Nana Sahib was broken and dispersed, and none

clearly knew whither it had gone. But those were days in which whole

races were looked upon as enemies, and whole cities were declared to be

guilty and blood-stained.

"Your comrades at Lucknow," said General Havelock in his order of thanks

to his men, “are in peril. Agra is besieged, Dehli is still the focus of

mutiny and rebellion. You must make great sacrifices if you would obtain

great results. Three cities have to be saved, two strong places to be

disblockaded. Your General is confident that he can accomplish all these

things."

Scarcely had the force reached Cawnpore, when drunkenness was upon it.

"Whilst I was winning a victory," said Havelock, "on the 16th, some of

my men were plundering the Commissariat on the line of march. And, once

within reach of the streets and bazaars of Cawnpore, strong drink of all

kinds, the plunder chiefly of our European shops and houses, was to be

had in abundance by all who were pleased to take it."

Large numbers of the Cawnpore population flocked panic stricken out

of the town to hide themselves in the adjacent villages, or to seek

safety on the Oude side of the river. Meanwhile, the British forces were

plundering in all directions, the Sikhs, as ever, showing an activity of

zeal in this their favorite pursuit. General Havelock set his face

steadfastly against it, and issued an order in which he said, "The

marauding in this camp exceeds the disorders which supervened on the

short-lived triumph of the miscreant Nana Sahib.” |

|

|

After the battle, the baffled Maratha had taken flight to Bithur,

attended by a few Sawars. On his journey, as he rode through Cawnpore, his horse no

doubt flecked with foam, criers were proclaiming that the English had

been well-nigh exterminated, and offered rewards for the heads of the few

who were still left upon the face of the earth. But the lie had

exploded, and his one thought at that moment was escape from the

pursuing Englishman. Arrived at Bithur, he saw clearly that the game was

up. His followers were fast deserting him. Many, it is said, reproached

him for his failure. All, we may be sure, clamored for pay. His

terror stricken imagination pictured a vast avenging army on his track

no doubt,

and the great instinct of self-preservation prompted him to gather up

the women of his family and embark by night on a boat, to ascend the

Ganges to Fathgarh, and to give out that he was preparing himself for

self-immolation.

He was to consign himself to the sacred waters of the Ganges, which had

been the grave of so many of his victims. There was to be a given

signal, through the darkness of the early night, which was to mark the

moment of the ex-Peshwa's suicidal immersion. But he had no thought of

dying. The signal light was extinguished, and a cry arose from the

religious mendicants who were assembled on the Cawnpore bank of the

river, and who believed that the Nana Sahib was dead. But, covered by

the darkness, he emerged upon the Oudh side of the Ganges, and his

escape was safely accomplished.After General Havelock captured

Cawnpore by defeating Nana Sahib in the hotly contested battle on June

16, 1857, Tantya Tope, the able General of Nana Sahib, was successful in

winning over the troops at Shivajinagar and Morar. With the concerted

strength of these troops Nana Sahib and Tantya Tope recaptured Cawnpore

in November 1857. But they could not keep Cawnpore under their charge

for long because the English General Campbell appeared there with a

large force. The British won a decisive victory against the forces of

Nana Sahib in the battle which was fought from

December 1st to the 6th, 1857. Nana Sahib fled towards Nepal,

where he probably died, while Tantya Tope migrated to Kalpi. |

|

|

|

|

| "I am not exaggerating," wrote one officer, "when I tell you that

the soles of my boots were more than covered with the blood of these

poor wretched creatures. Blood-stained clothing was scattered about, as

well as leaves ripped out of the Bible and out of another appropriately

titled book, Preparation for Death." On finding the scenes of murder,

and inflamed with anger, the English extracted revenge. Most of the

perpetrators had made good their escape, but the British made

captured Indians, whether involved or not, lick the blood stains of the

dead. Hindus were forced into eating beef, Muslims pork. The latter were

tied up in pigskin before being executed. Many inhabitants of Cawnpore

who had played no part in the violence were summarily executed for

having failed to do anything to prevent the killings. The preferred

method of execution was to blow the perpetrator from the guns as hanging

seemed to easy a death. The victim was tied to the muzzle of an

artillery gun and blown to pieces. Retribution had been brutal.

Where the woman and children were mercilessly killed, the British left

the room untouched, and filled in the

well of the house only partially, so that they could stand as

terrible reminders to new troops from England that their duty must be

sustained by a desire for revenge. One soldier, his head full of tales

of atrocities, reported: "I seed two Moors [Indians] talking in a cart.

Presently I heard one of 'em say 'Cawnpore.' I knowed what that meant;

so I fetched Tom Walker, and he heard 'em say 'Cawnpore,' and he knowed

what that meant. So we polished 'em both off."

The house in which they were butchered, and which is stained with

their blood, would not be washed or cleaned by their English countrymen,

but Brigadier-General Neill had determined that every stain of

that innocent blood shall be cleared up and wiped out, previous to their

execution, by such of the miscreants as may be hereafter apprehended,

who took an active part in the mutiny, to be selected according to their

rank, caste, and degree of guilt. Each miscreant, after sentence of

death is pronounced upon him, will be taken down to the house in

question, under a guard, and will be forced into cleaning up a small

portion of the blood-stains, the task will be made as revolting to his

feelings as possible, and the Provost Marshal will use the lash in

forcing any one objecting to complete his task. After properly clearing

up his portion, the culprit is to be immediately hanged, and for this

purpose a gallows will be erected close at hand!

The first culprit was a Subahdar of the 6th Native Infantry, a very high

Brahman. The sweeper's brush was put into his hands by a sweeper, and he

was ordered to set to work. He had about half a square foot to clean. He

made some objection, when down came the lash, and he yelled again. He

wiped it all up clean, and was then hung, and his remains buried in the

public road. Some days after, others were brought in. One a Muhammadan

officer of the civil court, a great rascal, and one of the leading men.

He rather objected, was flogged, made to lick part of the blood with his

tongue.

It was contended that, as there were different degrees of murder, there

should also be different degrees of death punishment. Colonel John

Nicholson, was eager to have a special Act passed, legalizing in

certain cases more cruel forms of execution, that is to say, death with

torture. "Let us," he wrote to Colonel Edwardes, at the end of May 1857,

"propose a Bill for the flaying alive, impalement, or burning of the

murderers of the women and children at Dehli. The idea of simply hanging

the perpetrators of such atrocities is maddening. I wish that I were in

that part of the world, that if necessary I might take the law into my

own hands."

Again, a few days later, vehemently urging this exceptional legislation:

“You do not answer me about the Bill for a new kind of death for the

murderers and dishonorers of our women. I will propose it alone if you

will not help me. I will not, if I can help it, see fiends of that stamp

let off with simple hanging." Edwardes, it seems, was naturally

reluctant to argue the question with his energetic friend, but Nicholson

could not rid himself of the thought that such acts of cruel retribution

were justified in every sense, and he appealed to Holy Writ in support

of the logical arguments which he adduced. Writing at a later period, he

said, "As regards torturing the murderers of the women and children; If

it be right otherwise, I do not think we should refrain from it, because

it is a Native custom. We are told in the Bible that stripes shall be

meted out according to faults, and, if hanging is sufficient

punishment for such wretches, it is too severe for ordinary mutineers.

If I had them in my power to-day, and knew that I were to die to-morrow,

I would inflict the most excruciating tortures I could think of on them

with a perfectly easy conscience. Our English nature appears to be

always in extremes. A few years ago men (frequently innocent) used to be

tortured merely on suspicion. Now there is no punishment worse than