| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Movie Trailer

The US$25 million production, set in the 1930s, is

ultimately about the spiritualism of an indigenous headhunting tribe in

Taiwan -- the Seediq.

The native people believe in bloodshed as the ticket into their version

of Heaven. Only by taking an enemy's head in battle can one cross the

mythical rainbow bridge into the heavenly hunting grounds.

It follows the Seediq tribe before and after the occupation of their

lands by Japanese imperial forces.

Life before the Japanese occupation is passionate and wildly beautiful;

battles fought under blood-red sakura blossoms, pig hunting along

pristine mountain streams, lusty boozing on mountain passes.

Under Japanese colonization, life for the Seediq is robbed of its

meaning. Hunting grounds are logged, indigenous culture is deemed

barbaric and young warriors are denied the rights to earn their

headhunting tattoos -- their passport across the rainbow bridge.

“In death, enemies become friends,” says protagonist Mouna Rudo, the

Seediq chief who bows to pressure to lead an uprising, based on a real

incident in Wushe. The rebellion thus becomes a spiritual decision.

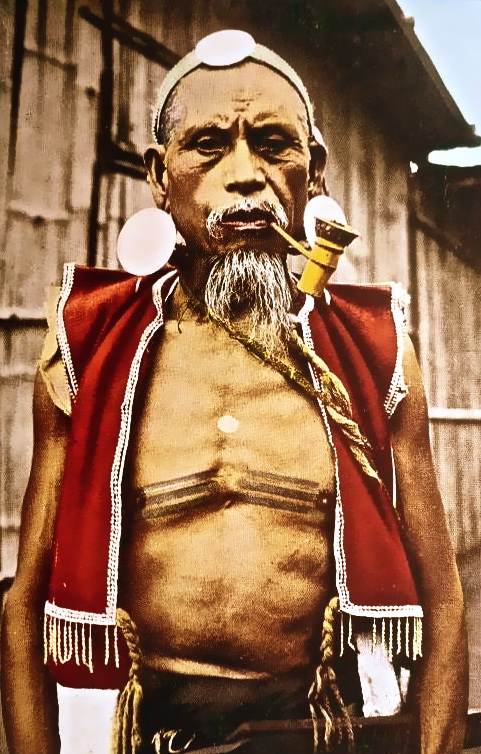

Taiwan Indigenous Culture

|

|

|

|

|

|

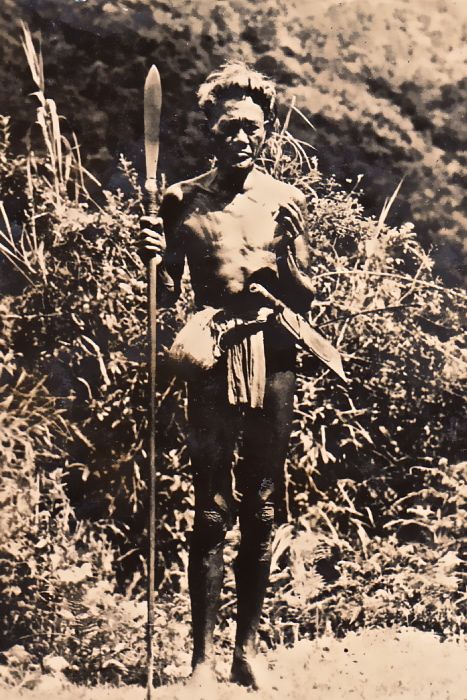

The Rover Incident of 1867

March 12, 1867, the American merchant ship Rover

hit a reef near Oluanpi, Taiwan's southernmost point, and drifted north

towards what is now Kenting. The ship soon sank, but the Captain, his

wife, and the crew got off in small boats. In revenge for previous

killings of local aborigines by foreigners, the local aborigines (called

the Koaluts at the time) killed everyone who made it to shore, excepting

one Chinese sailor. That sailor found his way to Takao (Kaohsiung),

where he notified the British consul, who in turn notified the British

ambassador in Beijing, who passed the information along to the US

ambassador there.

The British dispatched a gunboat from Taiwanfu (Tainan)

in late March to search for survivors. The aborigines descended on the

sailors searching the area, driving them back to the ship, which

responded by shelling them, and then leaving. |

|

|

|

|

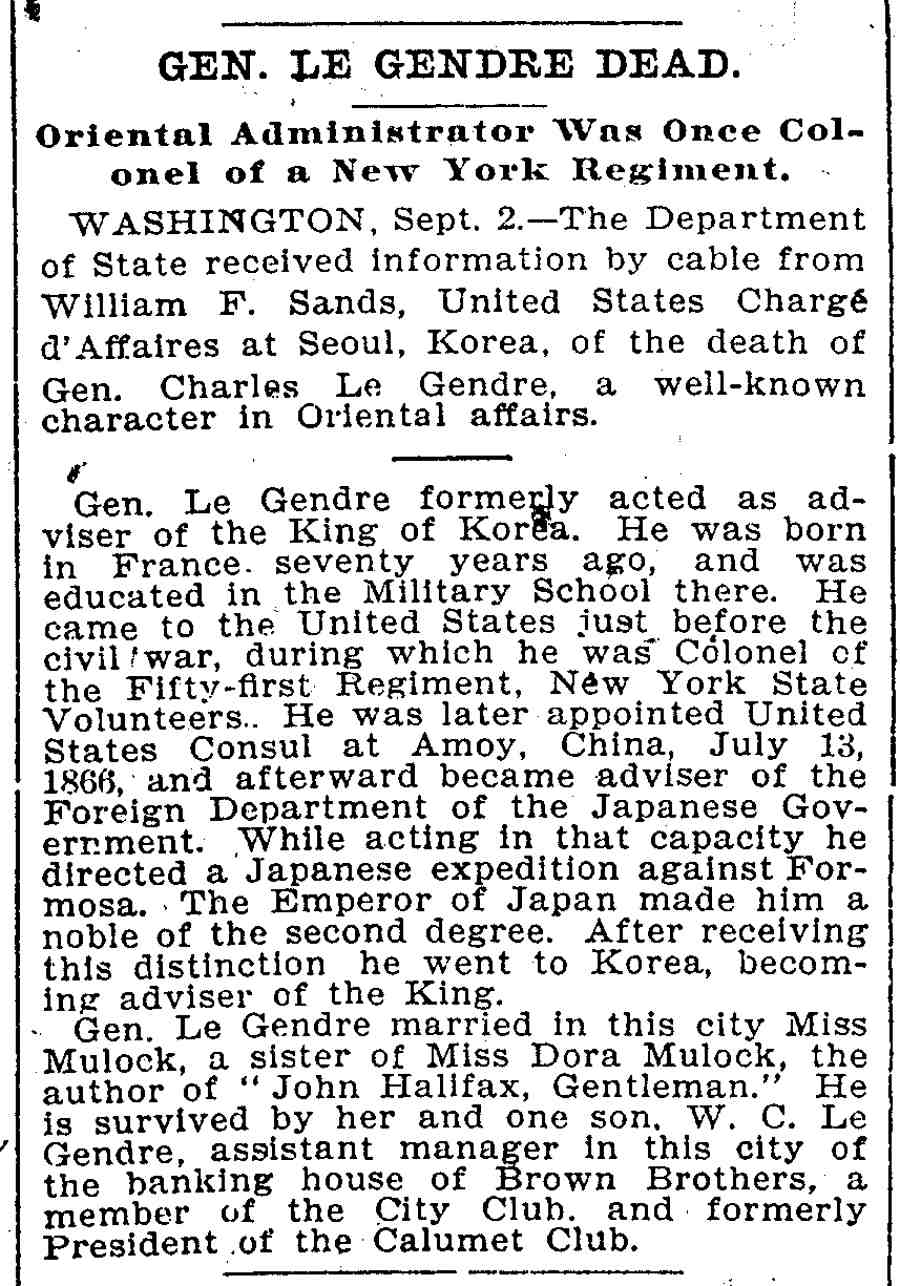

Charles William Le Gendre

Early in April of 1867 the US Consul in Amoy, Charles

William Le Gendre, traveled to Foochow to see whether he could persuade

the Ching authorities to act. The governor-general gave Le Gendre a

letter of introduction to the Ching official in Taiwanfu (Tainan). Le

Gendre arrived in Taiwan on April 18, where Ching authorities evinced

little interest in the incident. They told Le Gendre that the aboriginal

districts lay outside their authority.

Months went by as diplomatic messages were exchanged, and finally on

June 13, 1867, two ships, Hartford and Wyoming, along with 181 officers,

sailors and marines, were dispatched by the Americans to punish the

"savages", accompanied by the British consul at Takao and a couple of

British citizens. Davidson complains that this was far too late, since

even if some Americans had survived, it would be unlikely that any were

still alive after so long a delay.

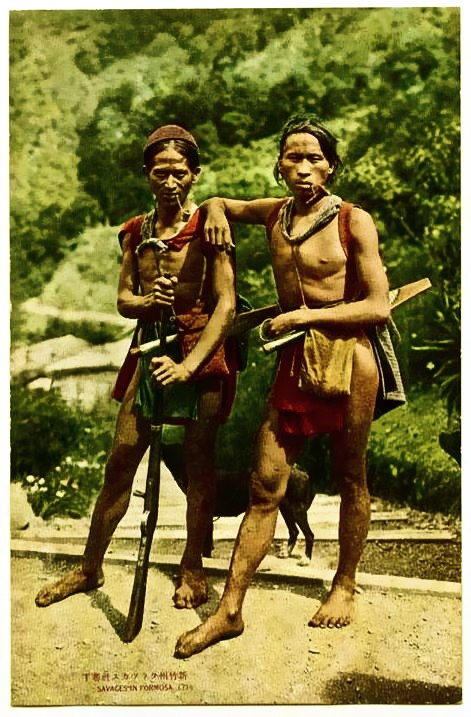

The marines and sailors landed on June 19th. The heat was overwhelming

and the troops were felled by sunstroke and exhaustion. "The savages,"

wrote the commander of the land expedition, "dressed in clouts, their

bodies painted red, were seen through our glasses, assembling in parties

of ten or twelve on the cleared hills about two miles distant." |

General Le Gendre

Brevet Medal

|

|

|

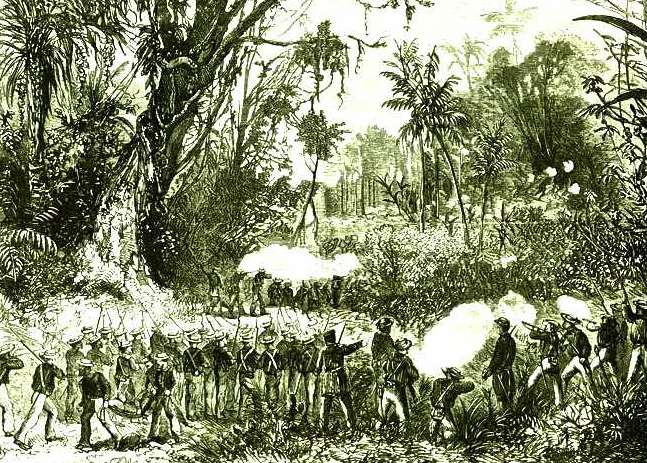

The aborigines sensibly fought from cover on a hill above the

Americans, remaining invisible to the American force but keeping the

sailors and marines under constant musket fire. "It was impossible to

tell the position of the enemy until we saw the smoke of his pieces, and

we were obliged to fire at the flash. We were in plain sight, an open

mark for the enemy, while they were hid in this undergrowth, into which

we could not see ten feet," complained one of the officers in the NY

Times. Forney was in charge of skirmishers deployed in front of the US

troops in this battle. After several hours of plunging into ambush,

the first battle casualty occurred when Alexander Slidell McKenzie,

second in command of the expedition, was killed leading a charge uphill

against the aborigines. Despite the Sharp's rifles that half the company

possessed (aborigines in southern Formosa had fled from volleys of the

new breech-loading rifles of the Prussian steamer Elbe in 1860, the

first use of the revolutionary new Prussian weapon in combat), they were

unable to drive off the locals. Instead, the "Pirates of Formosa" as

they were styled in the NY Times, had driven off the expedition in

defeat and disarray. The retreating Americans made up for the defeat by

burning a few huts on their way back to their ships.

The aborigines, observed the US ground commander, |

Captain James Forney

President U. S. Grant.

Washington City, April 13, 1869

To the Senate of the United States:

I nominate Capt. James Forney, of the Marine Corps, to be brevet major

in said corps for gallantry in action against the savages of Formosa, to

date from the 13th of June, 1867 |

| displayed "a stratagem and courage equal to our native Indians. After

this ineffectual attempt to bring the Koaluts to reason...."

Below, Marines in action against the "savages of Formosa"? James Forney

later became a civil war hero and rose to high rank in the Marines

before being court-martialed for corruption. |

|

Attack of the United States Marines and Sailors on the Pirates of the

Island of Formosa, East Indies |

A second attempt to "reason" with the aborigines was made by Le

Gendre. In September of 1867 he arrived in person on Formosa to take

charge of a punitive expedition with a large force, which the Ching

Viceroy had promised to send. Arriving with orders in hand from the

Ching authorities in China, he compelled the Ching general on Formosa in

charge of the island's troops to supply him with the troops, though only

500 of the promised 1,000 were delivered, and off he marched into

southern Taiwan.

Le Gendre had been a general in the civil war and was an experienced

leader of troops as well as an experienced diplomat. He basically

assumed control of the expedition from the Ching general in charge, and

led it on an exemplary march across hill and dale, road building along

the way, entirely free of violent encounters. |

| "We spent the night in a sugar mill, and left at daylight for

Pangliau, which we reached the same night. Pangliau extends along the

shore at the summit of an arc of a circle, forming a bay, and is,

therefore, too open to be secure. The products are rice and peanuts.

Women pound the rice and till the fields, while the men are entirely

taken up with fishing. To the east, at a cannon shot from the sea, rise

abruptly from the valley, high mountains, the exclusive domain of the

savage aborigines, who receive from the Chinese (or half-caste)

population a certain share of their crops, as a royalty for the lands

they have rented to them forever. There for the first time we notice

that none leave the village without being armed." Why did they wait at

Pangliau? They were having a road built over the mountains, which they

promptly set out on once it was completed. Despite predictions of

imminent attack, the expedition skillfully blocked the local passes with

troop detachments and proceeded unmolested into the aboriginal Demenses.

Le Gendre proved himself equal to the daunting tasks before him. He

recognized that retaliation was pointless and it would be better to

obtain a promise of future protection of shipwreck victims from the

local aborigines, which he described as consisting of 18 tribes led by a

paramount leader named Tooke-tok. It was US policy, he wrote, “to

sacrifice a vain revenge (which might be hereafter used as a pretext for

retaliation) to the incomparable advantage we would gain in securing

ourselves against the recurrence of crimes we had come to punish.” Le

Gendre also realized that the aborigines, far from acting out of some

savage preference for violence, were aggrieved parties retaliating for

attacks on them by foreigners. Finally, the large body of troops he had

brought represented muscle that could be deployed in punishment should

negotiations break down or agreements be broken.

Le Gendre was able to negotiate an agreement which saw attacks on

shipwreck victims in the vicinity fall. This agreement included a

provision calling for the Ching to build a "fortified observatory at the

southern bay" which would eventually evolve into the walled lighthouse

at Oluanpi. |

|

Le Gendre saw a fort in the area as an urgent necessity which would

enable the Ching to assert their authority over the area, command

respect from the Koaluts, and provide a safe haven for the many victims

of shipwrecks in the area. In response to Le Gendre's demands, the Ching

General Liu erected a walled enclosure in the area in just two days.

The mission was successful in that the local

aborigines often helped shipwreck victims and notified the Ching

authorities of their existence. But the "confederation" of local peoples

fell apart -- if indeed it had ever existed -- and Tooke-tok found it

difficult to exert his authority.

After "a hard trip of nearly two months", Le Gendre returned to Amoy. In

1874 he would return to the area with a Japanese punitive expedition as

its advisor, along with several other Americans. The Japanese were sent

to punish the aborigines for the murder of 54 Okinawan sailors by

aborigines of the Mudan area in 1871. The enterprise was doubly

colonialist, first against the aborigines, and second, against Okinawa.

By "avenging" those deaths, the Japanese would demonstrate that they

spoke for and acted on behalf of, the Okinawans as their rulers. That

expedition would lead to the famous Battle of the Stone Gate, not far

from modern Checheng. |

|