|

|

|

|

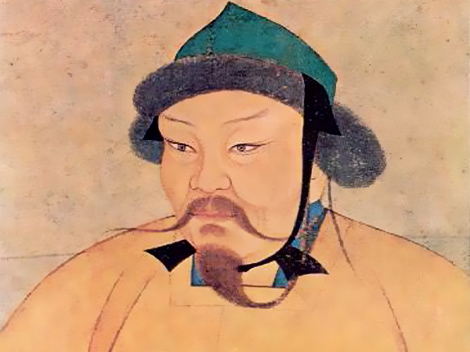

The Mighty Manslayer, the Scourge of

God, the Perfect Warrior and the Master of Thrones and Crowns, are some

of his many names. Historically today, he is most often remembered as

Genghis Khan.

Even the 'name' Genghis Khan is yet another title, originally,

Genghis Kha Khan, meaning the Greatest of Rulers or the Emperor of All

Men. It was bestowed in 1206 by a soothsayer, at the Kurultai, the

Council of the Khans, held to select a single man to rule all the

peoples of high Asia. The other name titles came later, after millions

had died in his wars of conquest. "God in

Heaven. The Kha Khan, the Power of God, on Earth. The seal of the

Emperor of Mankind."

The Seal of Genghis Khan

The story of Genghis Khan begins in the Gobi Desert, A.D. 1162, the Year

of the Swine in the calendar of the twelve beasts. |

|

|

|

| Genghis Khan's birth name was Temujin. At the time of his birth, his

father, Yesukai, was absent on a raid against a tribal enemy called

"Temujin" by name. The affair went well, the enemy was made a prisoner,

and the father, returning, gave to his infant son the name of the

defeated foeman. Temuchin signifies "The Finest Steel", Tumur-ji. The

Chinese version is T'ie mou jen, which has another meaning all together,

"Supreme Earth Man". Temujin was the first born of Yesukai

the Valiant, Khan of the Yakka Mongols, master of 40,000 tents. His

father's sworn brother was Toghrul Khan of the Karaits, the most

powerful of the Gobi nomads, he who gave birth in Europe to the tales of

Prester John of Asia. The Gobi Desert, lofty plateaus, wind-swept,

lying close to the clouds. Reed bordered lakes, visited by migratory

birds on their trek to the northern tundras. Huge Lake Baikul, visited

by all the demons of the upper air. In the clear nights of mid-winter,

the curtain of the Northern Lights Aurora Borealis rising and falling

above the horizon.

The Gobi Desert, as described by Friar Carpini, the first European to

enter this desolate land, circa mid 12th century. "In the middle of

summer there are terrible storms of thunder and lightning by which many

people are killed, and even then there are great falls of snow and such

tempests of cold winds blow that sometimes people can hardly sit on

horseback. A man cannot see through the prodigious dust storms. There

are often showers of hail, and sudden, intolerable heats followed by

extreme cold".

The children of the northern Gobi steppes were not hardened to

suffering, they were born to it. After they were weaned from their

mother's milk to mare's milk they were expected to manage for

themselves! The places nearest the fire in the family tent belonged to

the grown warriors and to guests. Women, it is true, could sit on the

left side, but at a distance, and the boys and girls had to fit in where

they could. Everything went into the pot and was eaten. The able-bodied

men taking the first portions, and the aged and the women received the

pot next, finally the children had to fight for bones and sinewy bits.

Very little was left for the dogs.

The end of winter was the worst of all for the Mongol children. No more

cattle could be killed off without thinning the herd too much. At such a

time the warriors of the tribe were raiding the food reserves of another

tribe, carrying off cattle and horses. The children learned to organize

hunts of their own, stalking dogs and rats with clubs or blunt arrows.

They learned to ride, too, on sheep, clinging to the wool.

The boys must fish the streams they passed in their trek from the

summer to winter pastures. The horse herds were in their charge, and

they had to ride far afield after lost animals, and to search for new

pasture lands. They watched the skyline for raiders, and spent many a

night in the snow without fires. Of necessity, they learned to keep the

saddle for several days at a time, and to go without cooked food for

three or four days, and sometimes without any food at all. |

Houlun - Mother of Genghis Khan |

For diversion they had horse races, twenty miles out into the

prairie and back, or wrestling matches in which bones were freely

broken. Mercy seemed to these nomad youths to be of little value, but

retribution was an obligation among the Mongol tribes.

Temujin's mother, Houlun, was beautiful, and so had been carried

off by his father from a neighboring tribe, on her wedding ride to the

tent of her betrothed husband. Houlun, made the best of circumstances

after some wailing, but all the yurt knew that some day men from her

tribe would come to avenge the wrong.

Temujin received word his father had been poisoned by enemies. Many of

his tribe then abandoned the standard of their chieftain and started off

to find other protectors, rather than trust themselves, their families

and herds to an inexperienced boy. "The deep water is gone," they said,

"the strong stone is broken. What have we to do with a woman and her

children?"

Temujin was now seated on the white horse-skin, Khan of the Yakka

Mongols, but had only a remnant of the tribe. He faced the certainty

that all the feudal foes of the Mongols would take advantage of his

fathers death to avenge themselves upon the son.

Then the inevitable, a certain warrior, Targoutai, announced that he

was now over-lord of the northern Gobi. Targoutai, chieftain of the

Taidjuts, the fuedal foes of the Mongols. |

| As an older wolf seeks and slays a cub too prone to take the

leadership of the pack, the hunt was launched without warning. Temujin

and his brothers fled before the onset of the horsemen. Thus the hunt

began with the Taidjuts close upon the heels of the boys. The chase

lasted for many days through gorges and timber growths and upon the

sides of mountains, and even into caves. Finally, Temujin was captured

alone, the brothers having separated days earlier. Targoutai commanded

that a 'kang' be placed upon him. A wooden yoke resting on the shoulders

and holding the wrists of the captive bound at each end. Later, left

alone with a single guard he knocked the man senseless with the kang and

escaped. Hearing the sound of pursuit he hid in a river with only his

head above water. Temujin observed one warrior spot him but say nothing

to the others. Following his trackers back to their camp he stealthily

entered the tent of the warrior, a guest of his pursuers, and he

assisted Temujin in escaping from the kang, and out of the camp to

safety. "The smoke of my house would have vanished, and my fire would

have died out forever had they found thee," the man remarked grimly to

the fugitive, giving to him at the same time food and milk, and a bow

with two arrows. "Go now to thy brothers and mother." |

| Temujin, riding a borrowed horse, tracked down his family. They were

in hiding and hungry; the stern mother Houlun, his brave brother Kassar,

and Belgutai the half bother who idolized him. They lived after a

fashion, traveling by night, trapping game, and Temujin learned how to

keep out of an ambush, and to break through the lines of men who hunted

him down. Hunted he was and his cunning grew with each passing year. He

was never in his lifetime captured a second time! Cunning kept Temujin

alive, and a growing wisdom kept the nucleus of a clan about him.

Physical prowess he had, and watchfulness. The chieftains who raided

into the fertile region between the Kerulon and Onon could drive him

from the hills into the lower plain, but could not bring him to bay.

"Temujin and his brothers," it was said, "are growing in strength."

Amidst the ceaseless, merciless warfare of the

nomad lands, Temujin

sought to master his heritage. At this time, when he was seventeen, he

went to look for his betrothed, Bourtai, to carry off his first wife.

|

|

Bourtai - Wife of Genghis Khan |

Bourtai was thirteen years old when Temujin arrived to claim her,

accompanied by 200 Mongol horsemen. Bourtai was singled out for a

destiny above that of other women. History knows her as Bourtai Fidjen,

the Empress, mother of three sons who ruled in a later day a dominion

greater than Rome's. But she was not long with her new husband before a

tragedy occurred.

Unexpectedly, a formidable clan rode down from the northern plain and

raided the Mongol camp. These were the Merkits. They were true

barbarians descended from the aboriginal stock of the Tundra, people

from the "frozen white world", where men traveled in sledges pulled by

dogs or reindeer. These were the clansmen of the warrior from whom

Temujin's mother, Houlun, had been stolen by his father some eighteen

years ago. Most probably they had not forgotten their old grievance.

They came at night, casting blazing torches into the Ordu (tent) of the

young khan. The Khan's new wife, Bourtai, was carried off by the

raiders.

Temujin, still lacking sufficient followers to retaliate, approached his

foster father Toghrul Khan, and besought the aid of the Karaits. Mongol

and Karait descended upon the raiders village during a moonlight night.

Temujin called Bourtai's name and she came to him in the confusion of

the attack.

He could never be certain if Bourtai's first born were his son, but his

devotion to her was unmistakable. He named his eldest son Juchi, the

"Guest", born under a shadow, but Temujin made no distinction among his

sons by her. They would come to inherit an empire lager than any other

ever to exist on Earth.

When the Mongols had grown to thirteen thousand horsemen, Temujin

fought his first pitched battle, against thirty thousand Tiajuts led by

Targoutai. There ensued one of the terrible steppe struggles - mounted

hordes, screaming with rage, closing in under arrow flights, wielding

short sabers, pulling their foes from the saddle with thrown lariats and

hooks attached to the ends of lances. |

| Each squadron fought as a separate command, and the fighting ranged

up and down the valley as the warriors scattered under a charge,

reformed and came on again. It lasted until daylight left the sky.

Temujin had won a decisive victory.

Temujin was accustomed to go to the summit of a bare mountain which

he believed to be the abiding place of the Tengri, the spirits of the

upper air that loosed the whirlwinds and thunder and all the

awe-inspiring phenomena of the boundless Sky. He prayed to the quarters

of the four winds, "Illimitable Heaven, do Thou favor me, send the

spirits of the upper air to befriend me, but on Earth send men to aid

me."

And men of courage and strength flocked to the standard of the "Nine

Yaks Tails" in ever increasing numbers. These paladins of the Khan were

known throughout the Gobi as the Kiyat, or "Raging Torrents". Two of

them, mere boys at the time, carried devastation over ninety degrees of

latitude in a later day. They were Chepe' Noyon, the Arrow Prince, and

Subotai Bahadur, the Valient, of the Uriankhi, the reindeer people. |

|

|

|

|

| There was no end to the tribal warfare of the Gobi, the wolf-like

struggle of the great clans, the harrying and the hunting down. The

Mongols were still one of the weaker peoples, though a hundred thousand

tents now followed the standard of the Khan. His cunning protected them,

his fierce courage emboldened his warriors. Temujin was more than thirty

years of age, in the fullness of his strength, and his sons now rode

with him. |

|

"Our elders have always told us," he said one day before the council,

"that different hearts and minds cannot be in one body. But this I

intend to bring about. I shall extend my authority over my neighbors."

To mold the venomous fighters into one confederacy of clans, to make his

feudal enemies his subjects, was his plan.

But then the twelfth century was drawing to a close, and Temujin in

his infinite patience was still laboring at what his elders said could

not be accomplished, a confederacy of the clans. He now realized it

could only come in one way, by the supremacy of one clan over the

others.

So Temujin approached

Prestor John, known as Toghrul Khan of the Keraits,

which were formed mostly of Nestorian Christians, who controlled the

cities on the caravan routes from the northern gates of Khitai (China)

to the distant west, and he formed a blood alliance between Mongol and

Kerait.

In his compact Temujin remained faithful to his new father. When the

Keraits were driven |

| out of their lands and cities by the western tribes, which were

mostly Moslems and Buddhists who cherished a warm religious hatred of

the Christian Shamanistic Karaits, Temujin sent his Mongol "Raging

Torrents" to aid the discomfited chieftain,

Prestor John. Behind

the Great Wall the "Golden Emperor" of Cathay (China) stirred in his

sleep and remembered incursions of the Buyar Lake Tatars that had

annoyed his frontiers. He announced that he himself would lead a grand

expedition beyond the wall to punish the offending tribesmen, an

announcement that filled his subjects with alarm! Eventually, a high

officer was dispatched with a Cathayan army against the Tatars, who

retired as usual unscathed and unchastened. The host of Cathay, being

composed largely of foot soldiers, could not come up upon the nomad

cavalry. Tidings of this reached Temujin, who acted as swiftly as hard

whipped ponies could carry his messages across the plains. He rallied

all his clansmen and sent to Prester John, reminding his elder ally that

the Tatars were the clan that had slain his father. The Keraits answered

his call, and the combined hordes rode down upon the Tatars who could

not retreat, because the Cathayans were in their rear.

The battle broke the Tatars power. The Cathayan general rewarded Prester

John with the title of Wang Khan, or "Lord of Kings". He awarded the

honor, "Commander Against Rebels", upon Temujin. The expeditionary force

and it's general then returned to Cathay, where he laid claim to all

credit for himself.

The Karaits offered a bride for Temujin's first born son, Juichi. A

young woman |

|

Tentengri, Mongol Wizard |

from among the girls of the chieftain's family. But Temujin remained in

his camp, keeping his distance warily from the Kerait ordus (tents),

while his men went before him to see if the way were safe. News came,

unwelcome and ominous. His enemies in the west; Chamuka the Cunning,

Toukta Beg, the chieftain of the dour Merkits, also the son of Wang

Khan, and Temujin's uncles, had determined to put an end to him. They

had persuaded the aging and hesitant Prester John, now Wang Khan, to

throw his strength in with theirs. The marriage overtures had been a

ruse.

With a small contingent of 6000 horsemen, merely an honor guard for the

marriage overtures, Temujin was heavily outnumbered, as he observed the

approach of his enemies. He saw the clans were scattered, the best

horses forging ahead of the slower paced. He led out his cavalry in

close array from their concealment, their horses rested, unlike those of

his former allies, which were hard pressed for speed. His initial charge

scattered the vanguard of the Keraits, and his horsemen formed their

lines across the rolling grassland, covering the retreat of his Ordu's

woman and children. Then Wang Khan and his chieftains came up, the Keraits realigned, and the merciless battle of extermination began on

the high steppes of Asia!

Never in his desperate life had Temujin been harder pressed. He had dire

need then of all the personal valor of his "Raging Torrents", and the

steadfastness of his household clans, the heavily armed riders of of the

Urut and Manhut clans that had always served him faithfully. His numbers

did not allow him to make a frontal attack, and so he was reduced to

holding what little advantage his ground position gave him, which for

Mongols was a last resort.

With his clans scattered and the Keraits and Merkits breaking through

his lines, and darkness coming on, Temujin ordered the tulughma, the

"standard sweep" that turns an enemy's flank and takes him in the rear.

It held the opposing cavalry in restraint, |

especially as the son of Wang Khan had been wounded in the face by

an arrow. When the sun set, the forces of Wang Khan withdrew a little

from the field, not the Mongols. Temujin waited only to cover

withdrawal, so as to gather up his wounded warriors, two of his sons

among them, many on captured horses and sometimes with two men on a

single animal. Then he fled to the east and the Keraits took up the

pursuit the next morning.

"We have fought," said Wang Khan, "a man with whom we should never have

quarreled." |

Temujin sent couriers and called a council of the khans. Each spoke

in turn. The bolder chieftains called for battle against the forces of

Wang Khan. They called for leadership from Temujin. This council

prevailed. Temujin accepted the command position and declared that his

orders must be obeyed in all clans, and his punishment immediate against

those he chose.

"From the beginning I have said to you that the lands between the three

rivers must have a master. You would not understand. Now, when you fear

Wang Khan will treat you as he has treated me, you have chosen me for

your leader. To you I have given captives, women, yurts and herds. Now I

shall keep for you the lands and customs of our ancestors."

During that cold dark winter the Gobi Desert divided into two rival

camps, and this time Temujin was first afield, before snow left the valleys.

With his new allies he advanced without warning upon the camp of Wang

Khan. By nightfall the Keraits were broken and scattered,

Prester John (Wang Khan) and his son both wounded and fleeing. |

|

|

Temujin gave to his men the wealth of the Keraits. The tent of Wang

Khan, hung with cloth of gold, he gave entirely to the two herders who

had warned him of the Kerait advance upon him, that first night at

Gupta.

Following up on the retreating Keraits, he surrounded them with his

cavalry and offered them their lives if they would yield, "Men fighting

as you have done to save your lord, are heroes. Be you among mine, and

serve me." The remnants of the Keraits joined his standard, and Temujin

pushed onward to their city in the desert, Karakorum, the Black Sands.

Prester John, once Wang Khan, who had entered into this war unwillingly,

fled hopelessly beyond his lands and was put to death by warriors of a

Turkish tribe. His skull was set in silver and remained in the tent of a

chieftain, as an object of veneration. His son was killed in much the

same manner.

"The merit of an action," Temujin told his sons, "is in finishing it to

the end."In the three years following the battle that gave Temujin

mastery of the Gobi steppes, he thrust his veteran horsemen far into the

valleys of the western Turks, from the long white mountains |

of the north, down the length of the Great Wall, through the ancient

cities of Bishbalik and Khoten his officers galloped, and Temujin

consolidated power.

For the moment clan feuds were forgotten, as they were in awe of the

Mongol Khan. Buddhist and shaman, devil-worshpper and muslim, and

Nestorian Christian, sat down as brothers, awaiting events. And Temujin

called his Kurultai, to select a single man to rule high Asia. And that

night his name changed to Genghis Khan.

"When he conquered

a province he did no harm to the people or their

property, but merely established some of his own men in the country

among them, while he led the remainder to the conquest of other

provinces. And when those he had conquered became aware how well and

safely he protected them against all others, and how they suffered no

ill at his hands, and saw what a noble prince he was, then they joined

him heart and soul and became his devoted followers. And when he had

thus gathered such a multitude that they seemed to cover the earth, he

began to think of conquering a great part of the world.", Marco Polo

wrote concerning Temujin. |

|

|

|

|

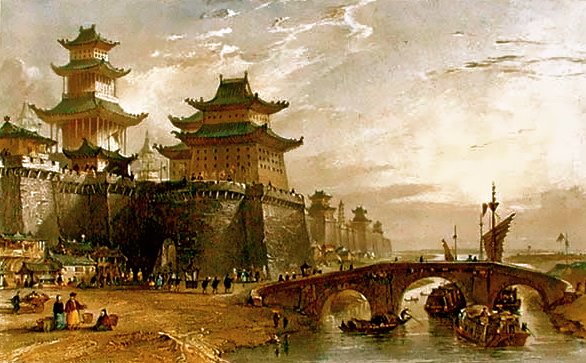

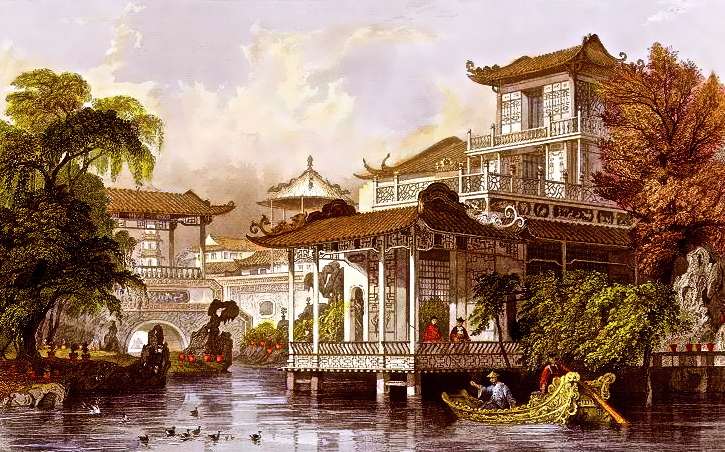

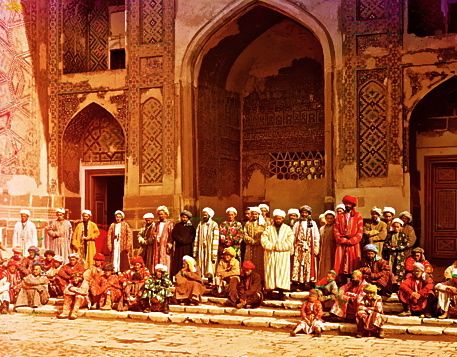

| Genghis Khan chose his headquarters, to which he always returned, at

Karakorum, the Black Sands, formerly the capital of the Kerait Khanate

under Wang Khan (Prester John). A wind-swept place of bitter sand storms,

Karakorum became a metropolis in a barren wasteland. Vast stables housed

the Khan's chosen herds of the finest horses. Granaries guarded against

famine. Caravanserais sheltered travelers and visiting ambassadors who

flocked to the Khan. There was a district to house the ambassadors and a

quarter for the religions. Buddhist Temples, stone Mosques, and small

wooden churches of Nestorian Christians, all stood next to one another.

Everyone was free to worship as they pleased.

Visitors were met by Mongol officers at the frontiers and

forwarded to Karakorum with guides, and word of their coming was sent

ahead by rapid couriers of the caravan routes. Once within sight on the

treeless and hill-less plain that surrounded the city of the Khan, the

travelers were taken in charge by the "Master of Law and Punishment".

When the Khan signified, they were led into his presence.

Genghis Khan's court was in a high pavilion of white felt, lined with

silk. By the entrance stood a silver table, set with mares milk, fruit

and meat, so that all who came to him could eat as much as they pleased.

In the center of the pavilion a fire of thorns and dung glowed. On a

dais at the far end sat the Great Khan. Ministers, scribes and Mongol

officers were about him in attendance. Utter silence would prevail when

the Khan spoke. When he said anything, that subject was closed. No man

might add a word to his. Words were few, and painstakingly exact. After

a person had presented themselves at the Khan's Ordu, they must not

depart until told to do so by the Khan.

With all merchants Genghis Khan established a method for dealing with

them. The Khan did not haggle. If the merchant tried to bargain with him

his goods were taken without payment. If, on the other hand, they gave

everything to the Khan, they received in return gifts that more than

paid them. To open up new roads between east and

west, and remain in continuous communication with all parts of his

empire, the Khan devised the yam or Mongol horse-post, the equivalent of

the pony express of thirteenth century Asia. These messengers were

accustomed to ride fifty or sixty miles a day. Past the yam stations

plodded the endless lines of camels and caravans. The yam was telegraph,

railroad and parcel-post, all in one. The Mongols were masters of the

roads. In the large towns there would be a daroga, or road governor,

with an absolute authority in his district. In this way the Khan could

receive dispatches from places ten days journey off in one day and

night. The post roads were the backbone of the Khan's administration.

|

|

|

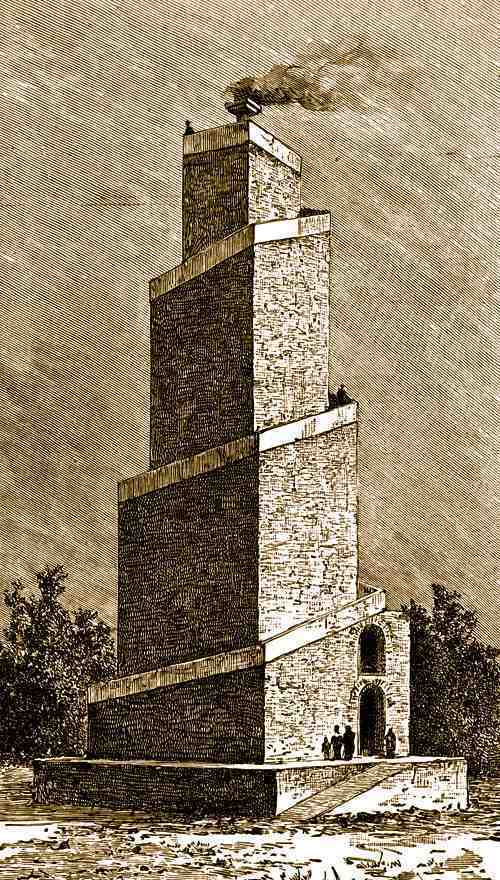

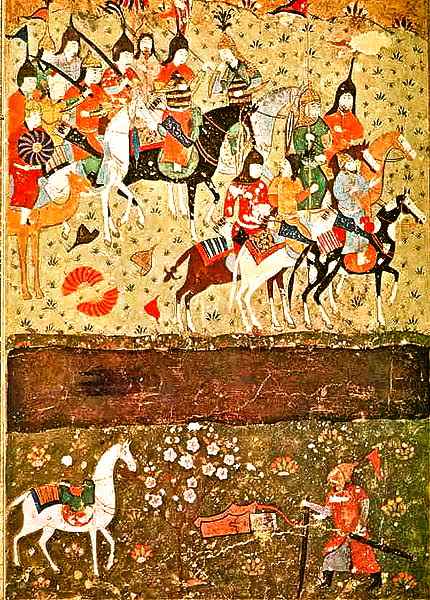

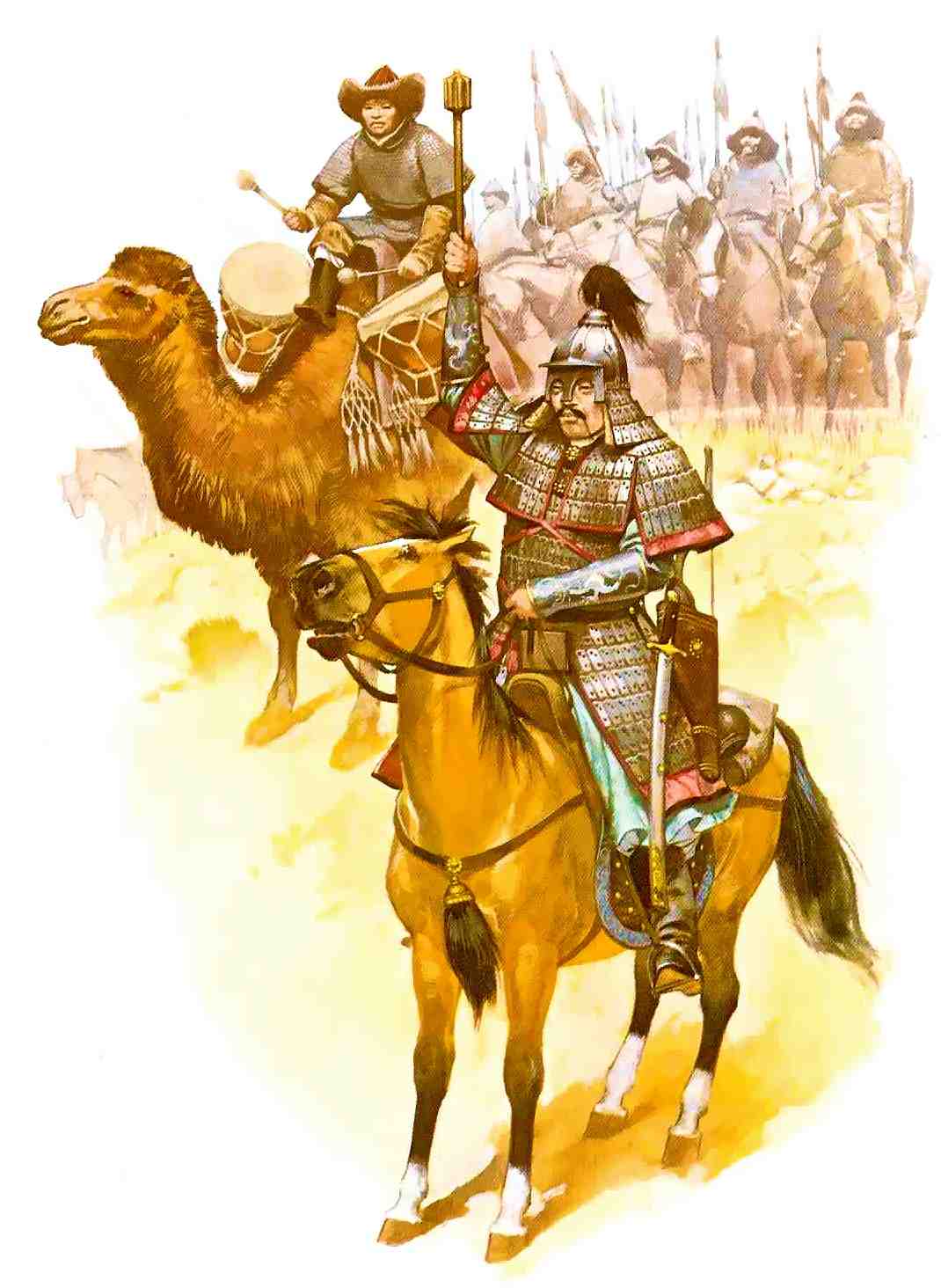

| For the first time in history the nomads were united into a

permanent military force as organized as the Roman Legions, which was

entirely because of Genghis Khan's efforts. The horde consisted of the

wise and mysterious Ugurs, the stalwart Keraits, the hardy Yakka

Mongols, the ferocious Tatars, the dour Merkits, silent men from the

snow Tundras, and all the riders of high Asia. There was nothing

haphazard about the Mongol Horde. It was composed of units of ten. It

was expressly forbidden for any warrior of the horde to forsake his

comrades, the men of his "ten". Or for the others of the ten to leave

behind a wounded man.

Ten of these formed the 'hundred'. Ten of the hundred formed the

'thousand'. Ten of the thousand formed a 'Tuman', a Mongol cavalry

division of 10,000. There were eleven divisions in all. Only 110,000

horsemen were the initial size of a highly mobile army that would

conquer most of the known civilized world. In command of each division

were the Orkhons, the Marshals of the Great Khan, drawn from the ranks

of the veteran "Raging Torrents". Genghis Khan had command of a new

force in warfare, a highly disciplined mass of heavy cavalry capable of

swift movement across all kinds of terrain. There had been cavalry

before, but not with the unique skills and tactics of the Mongols.

The Mongol cavalry remained invisible until the hour of battle and

then maneuvered in terrible silence, obedient to signals given by moving

the standards of the horde, signals repeated to the warriors of a

squadron by the arm movements of an officer. This, during the day and in

the clamor of conflict when the human voice could not be heard, and

cymbals and kettle drums might be mistaken with the enemy's own

instruments. At night, such signals were given by raising and lowering

colored lanterns near the standard of a commander.

The standard of Genghis Khan was the pole with nine white yaks tails.

It was forbidden for any of the horde to flee before the standard

withdrew from battle. It was forbidden to turn aside to pillage before

permission was given by the commanding officer. All men were entitled to

all they found, without interference from their superiors. Father Carpini wrote, Mongols "never leaving the field while the standard was

lifted, and never asking quarter if taken, or sparing a living foeman."

The Mongol method of tempering steel arrow heads was by plunging

them, while hot, into water mixed with salt, that they may be better

able to penetrate armor. Friar Carpini's vivid impression of the

devastating archery of the Mongol warriors, "Men and horses they wound

and slay with arrows, and when men and mounts are shattered in this

fashion, they then close in upon them."

The Kurultai was the summons that cannot be ignored. When the great

Khan called upon his officials and officers, all must respond! It was

the law. As Genghis Khan himself said, "Those who, instead of coming to

me to hear my instructions, remain absent in their cantonments, will

have the fate of a stone that is dropped into deep water, or an arrow

among reeds . . . they will disappear." |

|

|

|

|

| The Turko-Mongol people were all united for the first time in many

centuries, but they had lived too long governed by tribal customs as

varied as the men themselves. To contain their wild nature, Genghis Khan

used his already established military structure of veteran Mongols, and

also placed all Mongols in all clans under one law, Yassa Law (a

combination of his will and the most expedient of tribal customs). This

was possible, because in their ecstatic enthusiasm they believed Temujin,

now Genghis Khan, was in reality a "Bogdo", a sending from the Gods,

endowed with the "Power of Heaven".

In Yassa Law, though himself a man

of uncontrolled rages, Genghis Khan denied his people their most

cherished indulgence, violence. Additionally, adultery and theft carried

the death penalty. Spies, sodomites, false witnesses and black sorcerers

were put to death. But a man could not be found guilty unless caught in

the act of the crime, if he did not confess. Among the Mongols, an

illiterate people, a man's spoken word was a solemn oath. An accused

nomad usually admitted guilt. Some came to the Khan and asked for

punishment. The general of a division a thousand miles away from the

court of the Khan, submitted to be relieved of his command and executed,

at the order of the Khan, brought by a common courier!

The first law of the Yassa is remarkable. "It is ordered that all men

should believe in one God, creator of Heaven and earth, the sole giver

of goods and poverty, of life and death as pleases Him, whose power over

all things is absolute."

Genghis Khan was a deist, raised among the ragged and rascally

shamans of the Gobi, his code treated religious matters indulgently. An

unlikely array of priesthoods trailed after the Mongol camps, on their

way to war; leaders of faiths, devotees, criers of mosques, Nestorian

Christians, shamans and magicians, 'Saracen' soothsayers. And, quote

Father Rubruquis, "Wandering yellow and red lamas swinging prayer

wheels, some of them wearing stoles, painted with a likeness of the true

Christian Devil."

The Mongols worshipped the Blue Sky. The Yassa addressed a great

weakness of the Mongol peoples. The Mongols had a terrible terror of

thunder. During the severe storms of the Gobi Desert, this all powerful

fear overwhelmed them sometimes, and they hurled themselves into lakes

and rivers to escape the Wrath of the Sky. The Yassa therefore forbade

bathing during a thunder storm, with or without clothes.

The success of the Yassa can be gleaned from a contemporary, Father

Carpini, "They are obedient to their lords beyond any other people,

giving them vast reverence and never deceiving them in word or action.

They seldom quarrel, and brawls, wounds or slaying hardly ever happen.

Thieves and robbers are nowhere found, so that their houses and carts,

in which all their goods and treasures rest, are never locked or barred.

If any animal of their herd goes astray, the finder leaves it, or drives

it back to the officers who have charge of strays. Among themselves they

are courteous and though victuals is scarce, they share then freely.

They are very patient under privations, and though they may have fasted

for a day or two, will sing and make merry. In journeying they bear cold

or heat without complaining. They never fall out and though often drunk,

never quarrel in their cups."

Father Carpini describes Mongol attitude, "Toward other people they

are exceedingly proud and overbearing, looking upon all other men,

however noble, with contempt. For we saw in the Emperor's court the

great Duke of Russia, the son of the King of Georgia, and many sultans

and other great men who had no honor or respect. Indeed, even the Tatars

appointed to attend them, however low their own position, always went

before these high born captives and took the upper places."

Father Carpini finishes, "They are irritable and disdainful to other

men, and beyond belief deceitful. Whatever mischief they intend they

carefully conceal, that no one may provide against it. And the slaughter

of other people they consider as nothing." |

|

|

|

|

|

| The Mongols were not of the same race as the Chinese proper. They were

descended from the Tungusi of aboriginal stock, with a strong mixture of

Persian and Turkish blood. These were the nomads of high Asia that the

Greeks named Scythians. The Mongols were able to overcome the terrors of vast deserts, the

barriers of mountains and waterways, the severities of climate, and the

ravages of famine and pestilence. No dangers could appall them, no

stronghold could resist them, no prayer for mercy could move them.

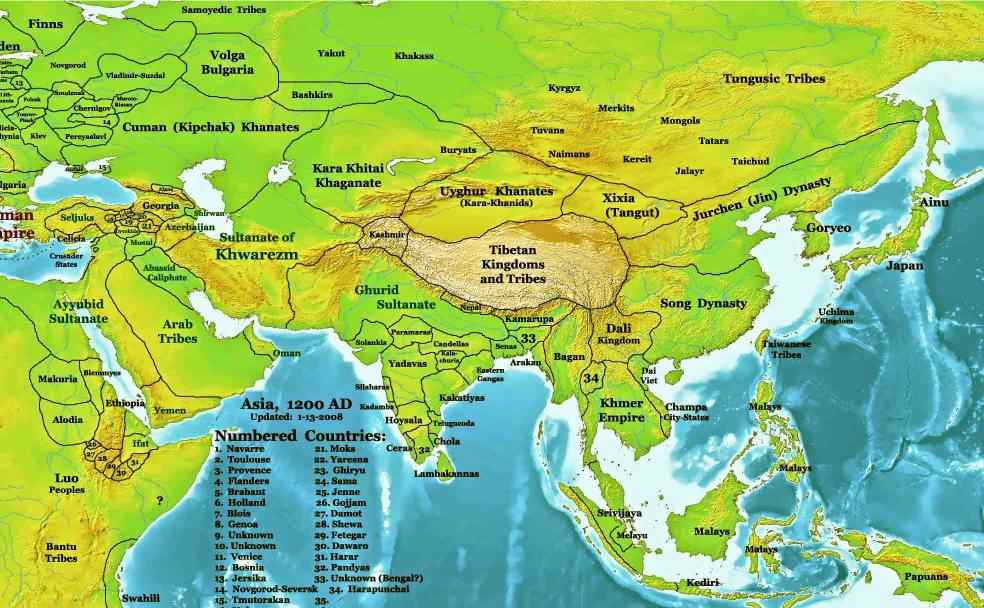

In 1206, the year

Genghis Khan united the Turko-Mongol peoples, the Khitai (Chinese) "Warden of the Western Marches", whose duty was to

watch over the barbarians beyond the Great Wall and collect tribute from

them, reported that "Absolute quiet prevails in the far kingdoms."

The Golden Emperor, in the course of his continual warfare with the

ancient house of Sung in the south, beyond the "Son of the Ocean", the

great Yang-tze river, sent emissaries to his subject, the Mongol "Commander

Against Rebels", to request the assistance of the nomad

horsemen. Genghis Khan responded immediately with two tumans of his

elite warriors. Chepe Noyon and other Orkhons commanded these cavalry

divisions. While in Khitai they used their eyes and asked questions.

They had the nomad ability to remember landmarks. They returned well

versed in the geography of Khitai. They also brought back to the Gobi

tales of wonders, such as the roads that ran clear across rivers.

High Asia was a troubled land. Along the ancient Nan-lu, the southern

caravan route, existed the curious kingdom of Hia, the so-called "Robber

Kingdom". Here were the lean and predatory Tibetan's, come down from the

mountains to plunder with their allies, the criminal outlaws of Khitai.

Beyond them extended the power of Black Cathy, in the T'ien Shan, a kind

of mountain empire, where Gutchluk ruled. And to the west, the roving

hordes of Kirghiz who had previously kept out of the Mongols path.

Against all these troublesome neighbors, Genghis Khan sent mounted

divisions, commanded by his veteran Orkhons. His war of raids in open

country convinced them it would be well to make peace with him. The

chieftains sent daughters to be wifes of the Khan, in order to

strengthen the bond. All this was preparation, cautionary, clearing his

flanks in military language.

Then the monarch of Khitai died and his son was seated on the Dragon

Throne. Genghis Khan refused to pay the tribute demanded by the new

Emperor Wai Wang, and sent an envoy to the imperial court with his

message. "Our dominion," said Genghis Khan, "is now so well ordered that

we can visit Khitai. Is the dominion of the Golden Khan so well ordered

that he can receive us? We will go with an army that is like a roaring

ocean. It matters not whether we are met by friendship or war. If the

Golden Khan chooses to be our friend, we will allow him the government

under us of his dominion; if he chooses war, it will last until one of

us is victor, one defeated."

Emperor Wai Wang called the Warden of the Western Marches to stand

before the 'Clouds of Heaven' imperial court and answer what the Mongols

were about. He replied they were making many arrows and gathering

horses. The Warden of the Western Marches was arrested and placed in prison.

Genghis Khan also sent envoys to the Liao-tung in the most northern

region of Khitai. These warlike spirits had not forgotten their conquest

by a previous Golden Emperor. The Liao Dynasty swore a compact with

Genghis Khan, and blood was drawn and arrows broken to bind it. The men

of Liao, means literally "Men of Iron". Liao would invade the north of

Khitai in conjunction with the Mongol Horde. In return the Great Khan

promised to restore all their previous power. Genghis Khan eventually

kept his word to the letter, making the princes of Liao the rulers of

Khitai, under himself. Genghis Khan had a limited number of warriors, and a single defeat

against Khitai could scatter the nomad clans back into their desert.

Genghis Khan would for the first time, need to maneuver his divisions against armies led by

masters of tactics.

|

|

|

|

|

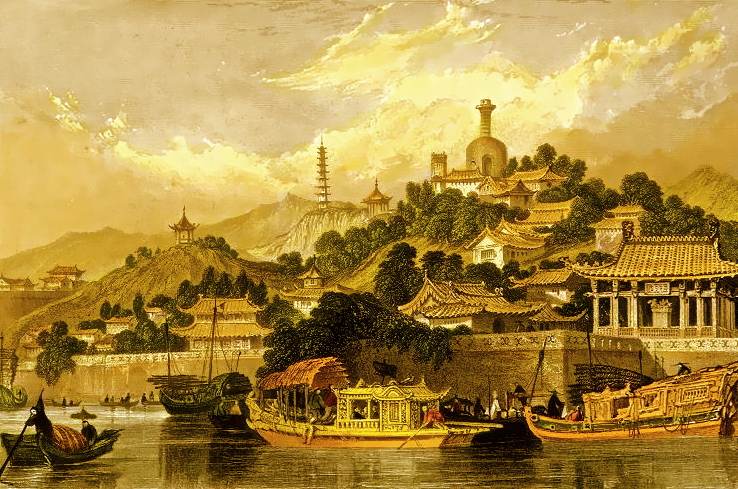

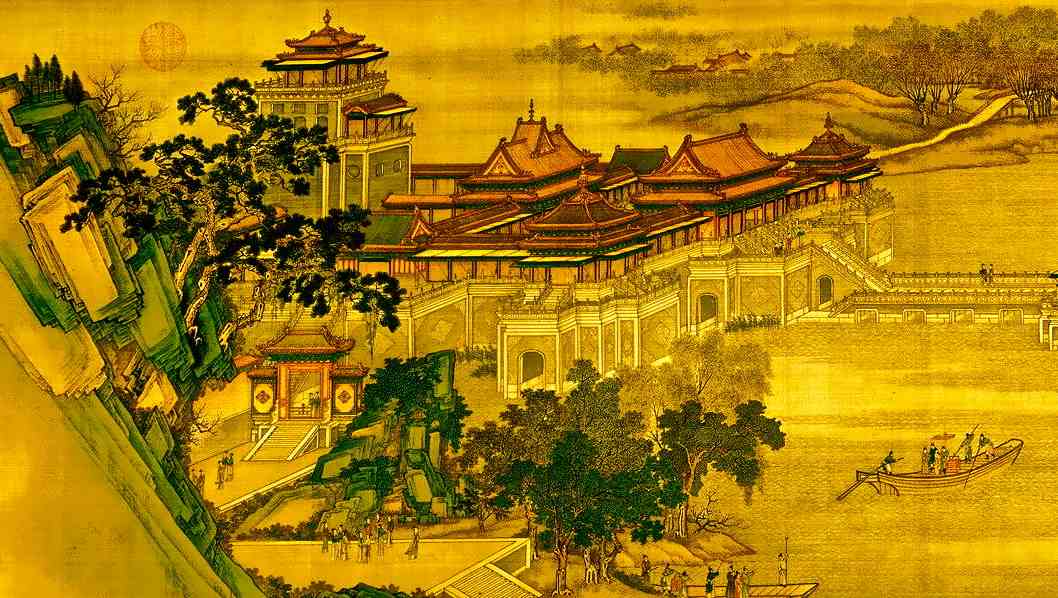

| The Mongol Tatars called the great kingdom of civilization beyond

the Gobi, Khitai (China). In Khitai existed a culture over five thousand

years old, with written records extending back more than thirty

centuries. The men of Khitai were not free and wild like the nomads of

the steppes. The men behind the Great Wall were mostly slaves, beggars

and peasants, with an aristocracy of scholars, soldiers, religious

mystics, mandarins, dukes and princes. Since time immemorial there had

always been an emperor, the "Son of Heaven", Tien Tsi, and a court, the

"Clouds of Heaven". In the year 1210, the 'Year of the Sheep' in the

calendar of the twelve beasts, the throne was occupied by the Chin or

Golden Dynasty. The court was at Yen-King, near the location of modern

Beijing.

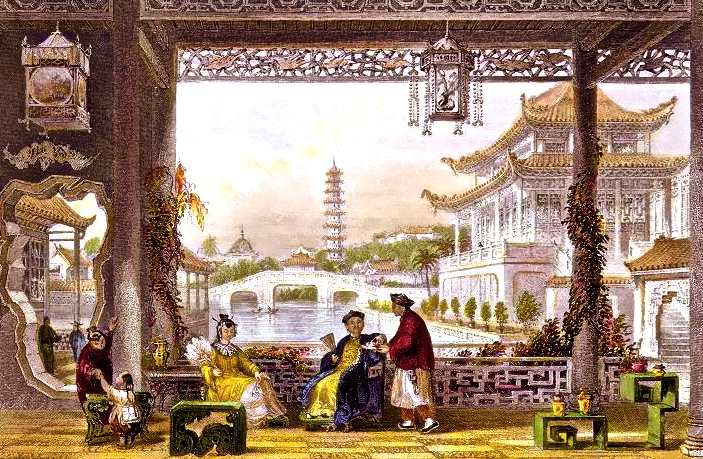

Within the great cities of Khitai, in the thirteenth century, over the

heads of high officials umbrellas were held, carried by slaves. Garments

were of floss silk multiply colored brilliantly. Inside the entrances of

dwellings, screens served to keep out wandering devils. Bamboo books

written in forgotten ages were studied and discussed at endlessly long

feasts. Within the cities were pleasure lakes and barges where men could

sip rice wine, and listen to the melody of silver bells in a woman's

hand. They might, perhaps, drift under a tiled pagoda roof, or hear the

summons of a temple gong. The pursuit of perfection is a laborious

process, but time did not have much meaning in Khitai. A painter

contented himself with touching silk with a bit of color . . . a bird on

a branch or a snow-capped mountain top. A detail, but a perfect detail.

A vagabond Taoist poet, in drunken contemplation, chasing the moon's

reflection in water, drowns, and is immortalized.

Kwan-ti, the War God, never lacked devotees. The

waging of war

had

been an Art in Khitai, since the days when the armored regiments and

chariots maneuvered over the wastes of Asia, and a temple was erected on

the battlefield, in the army camp, for the general commanding to

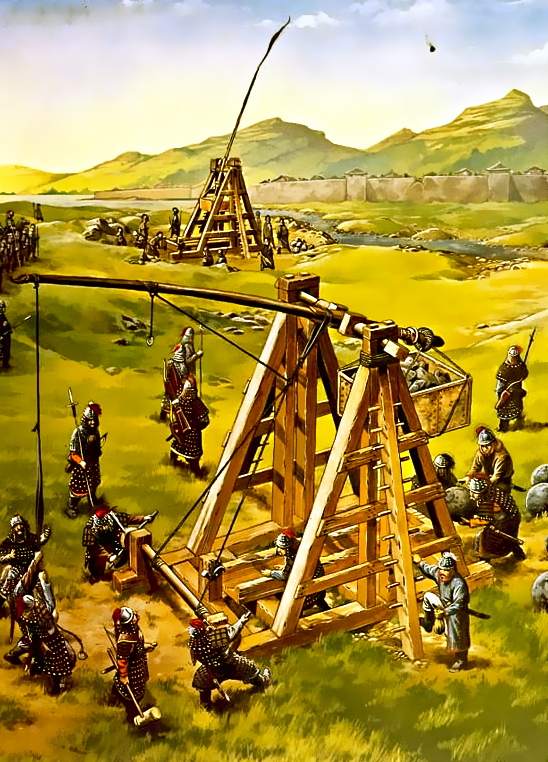

meditate upon strategy undisturbed. War engines Khitai had, twenty horse

chariots, ancient and useless, but also stone casters, crossbows the

strength of ten men could not wind, and catapults which required two

hundred artillerists to draw taut the massive ropes, which launched

great stones and the

"Fire That Flies".

|

|

|

|

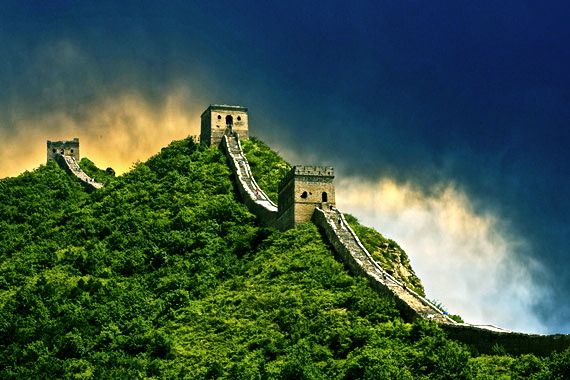

The ancient history of Khitai is plagued by barbarian invasions from

the Gobi. Long ago the Khitayan barbarians themselves had descended from

the north, and later, during the Warring States Period, the desert

tribes had been united, briefly, under the Hiung-nu monarchs who harried

ancient Khitai until the

Great Wall was built to shut them out, and only

a century ago came the Chin incursion. These invaders had always been

absorbed into the great multitude of peoples comprising the kingdom of Khitai. After a period the invaders fell into the manners of Khitai,

clad themselves in it's garments and followed it's ancient rituals.

|

|

The first of the Horde sent by Genghis Khan had long

since entered the Kingdom of Khitai. Spies and warriors, ordered to

capture and bring back informers to the tent of the Khan, had already

been at work behind the Great Wall for some time.

Next infiltrated the advance points, two hundred riders

scattered over the countryside in pairs, acting as scouts. Far behind

these scouts came the advance, thirty thousand veteran warriors, three

tumans (divisions), on the best horses, at least two horses for each

cavalryman. These were commanded by Muhuli, Chepe Noyon and Subotai,

chosen from the Khan's marshals.

In constant communication by courier horsemen with the

advance forces, the main body of the horde rolled like thunder over the

barren plateaus, out of the Gobi, a massive roiling cloud of dust

surrounding it's advance. |

| A hundred thousand, mostly Yakka Mongols of long, loyal service,

formed the center, with both the right and left wings half as many

warriors each. Genghis Khan always commanded the center, keeping his

youngest son, Tuli, at his side for instruction in war. The Khan himself

was constantly protected by his "Imperial Guard", one thousand hand

picked heavy cavalry, mounted on black horses with black leather armor.

The Horde approached the Great Wall unhindered, and passed through

that barrier without delay or the loss of a single man. Genghis Khan had

been tampering with the frontier tribes for some time, and so one of the

great gates was opened to him by sympathizers. |

|

|

| Once the wall was behind them the Mongol divisions separated to

carry out predetermined tasks. Highly mobile, they needed no base of

supplies. Mostly infantry, the forces of Khitai guarding the frontier

roads were decimated by arrows shot from the backs of fleet footed

horses, into the close packed formations of the foot soldiers.

One of the Emperor's armies on the road to war with the Mongol

invaders, lost it's way, and had to ask peasants for directions. Chepe

Noyon remembered the roads and valleys of the area from his service to

the previous Golden Emperor, by command of the Khan. He traversed the

difficult terrain of the region in the black of night and came upon the

Chin forces, unexpectedly from the rear, the next day. The Mongols broke

the cohesion of the Chin, and the scattered remnants of it, fleeing

east, brought fear to the largest army of Khitai, which was approaching.

This fear turned into terror and the commanding general fled back

towards the capital city. |

|

| Several cities were taken by the Mongols, but Taitong-fu, the

Western Court, still held out. Genghis Khan advanced toward the reigning

city, Yen-king itself. The devastation wrought by the Mongol horde

and it's near approach to the capital, filled Emperor Wai Wang with

alarm.

Now the greatest power of the Empire rallied to the defense of Khitai;

the innumerable multitudes, the devoted throngs, born from a line of

warlike ancestors, they knew no higher duty than to die for the throne.

The sleeping giant was shocked from slumber. New armies appeared,

approaching along the great rivers, and the garrisons of cities seemed

to multiply daily. |

| When Genghis Khan reached the capital at Yen-king, and beheld for

the first time the magnificence of the high walls, and row upon row of

citadel fortresses, he realized the war could last lifetimes. He drew

back immediately from Yen-king, and in the autumn withdrew the horde to

the Gobi.

In the spring, upon fresh horses, Genghis Khan appeared again,

suddenly, inside the Great Wall. Those frontier towns that had

previously surrendered were now garrisoned and defiant. The Khan set to

work and laid siege again to the Western Court at Taitong-fu. As the

Chin infantry armies approached to relieve the siege of the court, they

were cut to pieces and scattered by the Mongol cavalry tactics that

whirled around in circular patterns, and loosed clouds of arrows upon

retreating. But the Mongol allies, the Liao princes, were sorely beset

by a Chin army of sixty thousand far up in the north of Khitai,

and requested the aid of the Khan. Genghis Khan was forced to dispatch a

division north, under the Orkhon marshal Chepe Noyon, who destroyed the

enemy with his tuman, and the art of deception.

Meanwhile, the Kha Khan, pressing vigorously the siege at the Western

Court, was wounded. The Mongol horde withdrew from Khitai, as the tide

ebbs from the shore, bearing their wounded chieftain with it.

The Mongol cavalry could out maneuver and decimate the armies of

Khitai in open battle, but did not have the siege warfare experience

necessary to take walled heavily garrisoned cities.

In the north the Chin military expeditions were prevailing against

the Iron Men of Liao-tung, and the riders of Hia, who guarded the flanks

of the Khan. |

|

|

|

Early spring of 1214, Genghis Khan launches three Mongol

armies into Khitai. In the south, three sons of the Khan, Ogotai,

Chatagai and Tuli cut a wide range of devastation. In the north, the

eldest son, Juchi, crossed the Khingan range and joined forces with the

Iron Men of Liao-tung. Genghis Khan forged the Mongol center of the

Horde deep into Khitai, to the very shores of the great ocean behind the

capital at Yen-king.

Genghis Khan ordered his divisions to wage war with a

new strategy of terror. |

| As the Mongol tumans rode across the countryside, in approach of

cities or garrisoned strongholds, they swept up the people and drove

them before the approaching Horde, in the first wave of the onslaught.

When a city resisted they settled down to a siege. When the citizens of

a city opened their gates and surrendered they were spared their lives,

even as everything in the open country was annihilated and driven off;

crops trampled, herds rustled, men, women and children cut down.

Refugees carried word of this far and wide across Khitai. As the

season of war drew to a close with autumn, and the Mongols would need to

return to the Gobi, Genghis Khan, laying siege to Yen-king, sent a

message to the Golden Emperor, besieged in Yen-king. "What do you think

now of the war between us? All the provinces north of the Yellow River

are in my power. I am going to my homeland. But could you permit my

officers to go away without sending gifts to appease them?"

The Chin monarch, Wai Wang, a man in terrible fear, agreed to a

truce. A lady of the reigning family was sent to Genghis Khan as a wife.

A thousand young male and female slaves carrying silks and gold, and

also a herd of the finest horses, were sent to the Khan. And so Genghis

Khan turned back to the Gobi and when he reached it's edge he put to

death the multitude of captives carried along by the Horde. They

wouldn't have survived the trek through the wastelands, and human life

had no value in the eyes of the Mongols. They desired only to depopulate

fertile lands to provide grazing for their herds. It was the Mongol

boast, at the long end of the war against Khitai, that their horses

could be ridden without stumbling across the sites of what had been

great cities. It was the custom of the Mongols to put to death all

captives, except artisans and savants, when they returned home after a

campaign. |

| The Golden Emperor was shaken, "We announce to our subjects that we

will change our residence to the capital of the south." Wei Wang fled

south. Rebellion followed upon his flight! Some troops escorting the

Golden Emperor mutinied and abandoned the monarch. The defense of Khitai

was left to hereditary princes, officials and mandarins.

In the face of danger the populace rallied, as the deep spirit of

loyalty to Khitai manifested. The flame kindled stirred up a firestorm.

Mongol garrisons and outposts were attacked. A relief army was sent to

Liao-tung with great success. The sudden reversal became known to

Genghis Khan. When his understanding was complete he acted immediately.

The Horde was at the end of a season of war. The horses were

exhausted, sickness was within the camps, provisions were low, but the

Khan chose the best division and ordered it south toward the Yellow

River to pursue the fleeing Emperor. It was now winter, but the Mongols

pushed on swiftly, forcing the lord of the Chins to cross the river into

the domain of his old enemies the Sung Dynasty. Even there the Mongol

division followed him, feeling their way among snow covered mountains,

crossing ravines on spear shafts and the branches of trees bound

together with chains. The imperial fugitive appealed for aid to

the Sung court. |

Emperor Wei Wang |

| Couriers sent by Genghis Khan recalled the tuman, and they made a

wide circle of the Sung cities, crossing the Yellow River surface on the

ice of winter, to return to the Horde. Genghis Khan was at the center of the Horde, camped near the wall.

Reports constantly arrived by couriers, riding hard pressed horses, and

not dismounting to cook food or take sleep while en route. The Khan was

now fifty five years of age. His sons were now grown men. Genghis Khan's

favorite grandson Kublai had been born. |

|

|

| It was Muhuli, aided by Mingan, a prince of Liao-tung, who directed

the thrust at Yen-king. With no more than five thousand Mongols under

his command, he traveled eastward gathering up a multitude of Khitai's

deserters and wandering bands of warriors. With Subotai covering his

flank he pitched tents before the outer walls of Yen-king.

Yen-king could have endured, but it was a city in chaos. With the

first breakout of fighting in the suburbs one of the Chin generals

deserted. Looting began in the merchants district, and streets were

filled with wandering, frightened soldiery. Fire followed, appearing in

various parts of the city. In the palace itself, eunuchs and slaves

flitted through the corridors, arms full of gold and silver ornaments.

The 'Hall of Audience' was deserted, and the sentries left their posts

to join the pillagers.

Wang-Yen, the commanding general, a prince of royal blood, considered

matters as hopeless, and so prepared to die as custom required. He

retired to his chambers and wrote a petition acknowledging he had been

unable to defend Yen-king and was worthy of death. This was written on

the lapel of his coat. His wealth he divided among his servants. Next,

he ordered his attendant mandarin to prepare a cup of poison.

When Wang-Yen drank his poison Yen-king was in flames, and the

Mongols rode in upon a scene of defenseless terror. The methodical

Muhuli, indifferent to the passing of a dynasty, occupied himself

|

Muhuli |

|

with collecting and sending to the Khan the treasures and the

munitions of the city.

Genghis Khan left the military government of Khitai, and the eventual

conquest of the southern Sung Dynasty to Muhuli, praising him publicly

and bestowing on him a banner embroidered with nine white yak-tails. "In

this region," he explained to his Mongols, "the commands of Muhuli are

to be obeyed as my commands."

No higher office could have been bestowed on the veteran Orkhon.

Genghis Khan kept to his word and left Muhuli undisturbed, with his

portion of the horde now under his iron will.

For the civil authority of Khitai Genghis Khan appointed governors

from among the Liao-tung men. |

| The Khan admired the courage of the mandarins who had carried on the

war after the desertion of their Emperor, and in the hardihood and

wisdom of these men he discovered something useful to himself. Ye Liu

Chutsai, for instance, could name the stars and explain their portents.

When he carried back with him to Karakorum the golden treasures of

Khitai, he took also members of the literati; scribes, scholars and

philosophers. Of all Genghis Khan's many sons he recognized only those born of

Bourtai as his heirs. They had been his close companions, he had

observed them continuously, bestowing early upon each of them a tutor,

drawn from the ranks of his best veteran officers. His youngest son,

Tuli, was carried beside his father to war upon a throne of human

skulls. When the Khan had satisfied himself as to his sons different

natures and abilities he made them "Orluks" (Eagles), princes of the

imperial blood. Genghis Khan designated their duties. Juchi, the first

born, was 'Master of Hunting'. Chatagai became 'Master of the Law and

Punishment'. Ogotai was 'Master of Council'. The youngest, Tuli,

nominally chief of the army, the Khan kept close, at the Mongol center.

And now, from the China Sea to the Aral Sea one master

reigned. Rebellion had ceased. The couriers of the Great Khan galloped

over fifty degrees of longitude, and it was said that a virgin carrying

a sack of gold could ride unharmed from one border of the nomad empire

to the other. Envoys of the Khan, bearded men of Khitai, intoned the new

law of the conqueror, appearing everywhere, bringing order out of chaos.

The shadow of the Yassa fell upon the conquered lands.

The "Master of Thrones and Crowns" was soon to become

the "Scourge". His next war of conquest was terrible in its

effect, and it was toward the west, toward the very heart of Islam.

|

|

|

|

|

.jpg) |

|

|

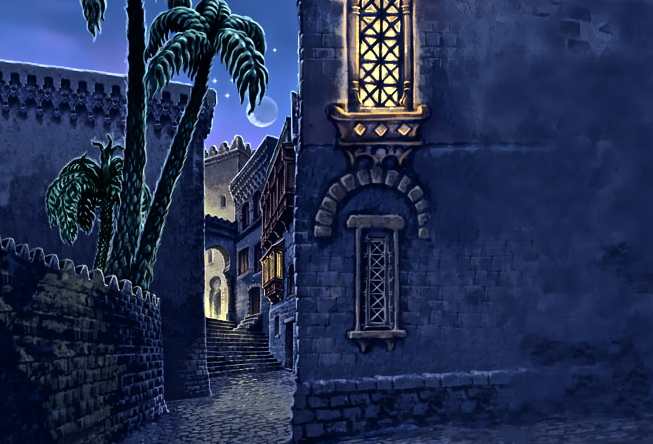

For the moment Genghis Khan was interested in trade. To the west was

the great barrier of mid-Asia, a treacherous network of mountain ranges

that extended northeast and southwest of the Taghbumbash, the "Roof of

the World". From time immemorial this mountain obstacle had existed. It

stood, vast and desolate, between the nomads of the Gobi Desert and the

rest of the world. These mountains separated the plains-dwellers of

Genghis Khan from the valley-dwellers of the west, which land was called

Ta-tsin, the "Far Country".

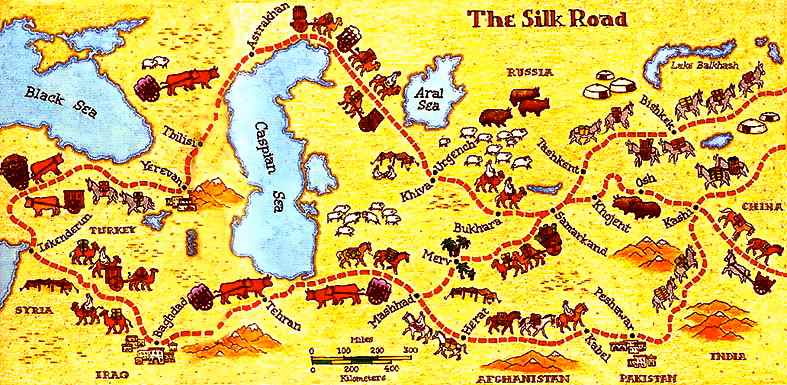

The caravans of the ancient Silk Road traversed this massive, difficult,

continental barrier regularly, and the merchants informed the Khan of

many wondrous things. On the other side of Taghbumbash there existed

fertile valleys where snow never fell. Here, also, were rivers that

never froze. Here multitudinous peoples lived in cities more ancient

than Karakorum or Yen-king. And from these people came the caravans that

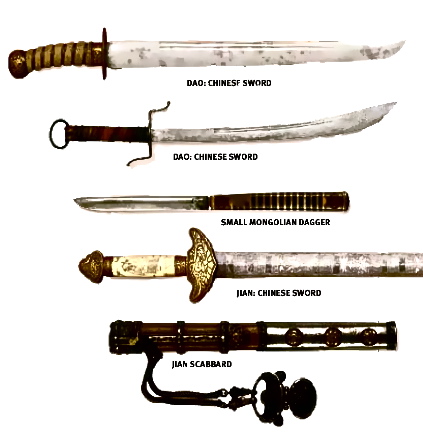

brought finely tempered steel blades and the best chain mail, also white

cloth and red leather, ambergris and ivory, turquoise and rubies. |

|

|

Ala-eddin Muhammad the Shah of Khwarezm

|

And so, Genghis Khan determined to trade with the west for the fine

weaponry of the Moslem armorers. He encouraged his own merchants,

subject Moslems themselves, to send caravans to the west. He learned

that his nearest neighbor to the west was Ala-eddin Muhammad, the Shah

of Khwarezm, himself a conqueror of a large kingdom. To this Shah the

Khan sent envoys, and a message, "I send thee greeting. I know thy power

and the great extent of thine empire, and I look upon thee as a most

cherished son. On thy part, thou must know that I have conquered Khitai

and many Turkish nations. My country is an encampment of warriors, a

mine of silver, and I have no need of other lands. To me it seems that

we have an equal interest in encouraging trade between our subjects."

The envoys of the Great Khan brought rich gifts to the Shah, bars of

silver, precious jade, and white camel's hair robes. "Who is Genghis

Khan?", demanded Muhammad Shah, "Has he really conquered Khitai?" The

envoys replied that this was so."Are his armies as great as mine?",

questioned the Shah. The envoys, in fear, replied that the horde of the

Khan could not be compared to the host of Khwarezm. The Shah was

satisfied and agreed to trade between kingdoms. For several years all

was well between them and trade prospered.

Then one Inaljuk, governor of Otrar, a frontier citadel of the Shah,

seized |

a caravan of several hundred merchants from Karakorum. Inaljuk sent

message to his Shah that the caravan carried spies. The merchants were

put to death upon Muhammad Shah's order. News of this eventually reached

the ears of Genghis Khan, who immediately dispatched envoys to the Shah

Muhammad in protest. The Khitai emissaries were bearded, so the Shah

slayed the chief envoy, burned the beards off the others, and sent them

back to the Gobi.

And Genghis Khan went off alone, to a mountain, and did long meditate

upon the events. "There cannot be two suns in the heavens," the Khan

said, "or two Kha Khans upon the earth."

Now, truly, spies were sent in numbers through the treacherous mountain

ranges and couriers traveled fast across the desert miles to summon men

to the standard of the Khan. Genghis Khan sent an ominous message to the

Shah of Khwarezm, "Thou hast chosen war. That will happen which will

happen, and what it is to be, we know not. God alone knows." |

|

|

|

|

Islam was a martial world. Centuries ago it's Prophet

had lighted a fire that had been spread by his followers and their

swords. An orphan of the Khoraish Clan in the desert near the Red Sea

preached a new faith. He harangued the Arabs, telling them there was no

more than one God. The Arab peoples had worshiped until then many gods

and demons, and a great black stone. His name was Muhammad, son of

Abdullah, and he made a multitude tremble at his description of the day

of judgment. When Muhammad died in 632 A.D., as a result of being

poisoned, the multitude accepted Islam (submission), and the Koran

(recitation). There was one God, and Muhammad, the son of Abdullah, had

been His Prophet.

Under the Companions, who had been the Disciples of the

Prophet, the mad rush of conquest began. In less than a century the

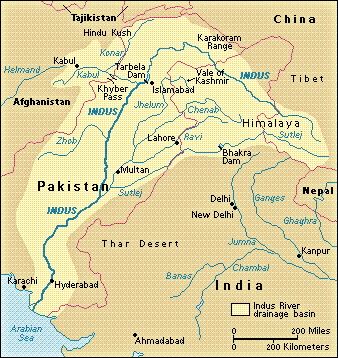

banners of Islam had been carried east as far as the Indus and the

outposts of Khitai. The swords of Islam were flashing in the deep gorges

of Caucasus. Egypt had fallen to them, and all of north Africa, and

Andalus (Spain). Two obstacles checked the tide of the Muhammadans upon

Europe. Charles the Hammer, king of the Franks, withstood them in the

west. In the east they were flung back from the walls of Byzantium, the Eastern Roman Empire. |

| In time the military power of Islam passed from the Arabs to the

Turks, but both joined in the Jihad holy war against the mailed host of

Christian crusaders that came to wrest Jerusalem from them, empowered by

the edict of the Pope. Now, in the beginning of the thirteenth century

Islam was at the height of it's military power. The weakening Christian

crusaders had been driven to the coast of the Holy Land, and the first

wave of the Turks were taking Asia Minor away from the soldiery of the

degenerate Greek empire. At the very center of Islam, Muhammad Shah of

Khwarezm had established himself as war lord. His vast domain extended

from India to

Baghdad, and from the Sea of Aral to the Persian Gulf.

Except for the Seljuk Turks, victorious over the crusaders, and the

rising |

|

Mamluk Dynasty in Egypt, his authority was supreme. He and his

Atabegs or father-chieftains, were Turks. A true warrior of Turan, he

had something of military genius, and a grasp of things political. He

was called "Muhammad the Warrior". The core of his host of four hundred

thousand was composed of Khwarezm Turks, but he had besides the armies

of the Persians at his summons. War elephants, huge camel trains, and a

multitude of armed slaves followed him.

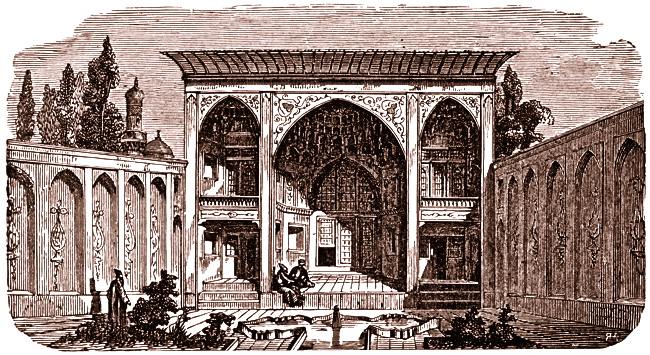

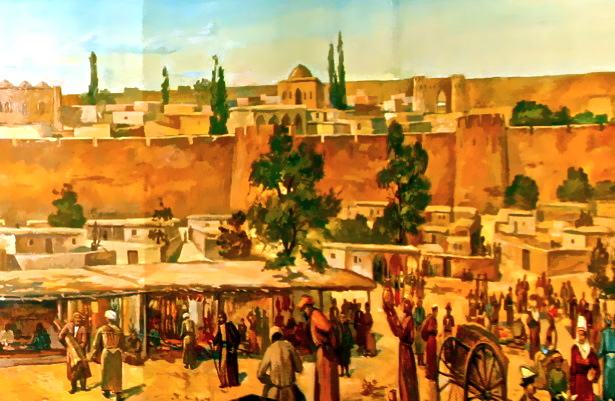

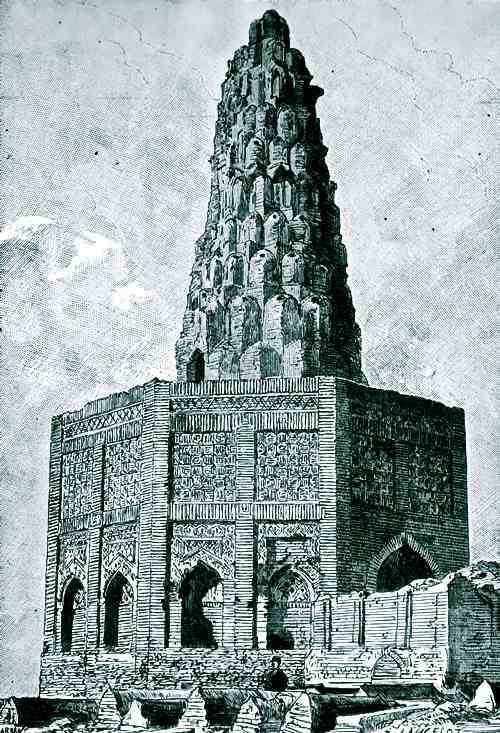

A main defense of the Khwarezm Sultanate was a chain of great cities

along the rivers; Bokhara the center of Islam's academies and mosques,

Samarkand of the lofty walls and pleasure gardens, Balkh and Herat, the

heart of Khorassan. This world of Islam, with an ambitious Shah,

multitudes of warriors, and mighty cities, was almost completely unknown

to Genghis Khan, far away in the Gobi Desert. |

|

|

|

Genghis Khan prepared for war. Muhuli continued his assault on

Khitai, and the princes of Liao were busy restoring order behind him.

From Karakorum the Khan scanned his empire through carefully chosen

agents, looking for anyone, but especially men of family and

ambition, who might cause trouble in his absence.

These received the kurultai, the summons that cannot be ignored, and were drafted into the

war machine of the Khan. The government of the Empire itself, he

determined to control wherever he traveled. He would communicate by

courier messenger system in administration, as he had in war. A brother

he left as governor in Karakorum.

|

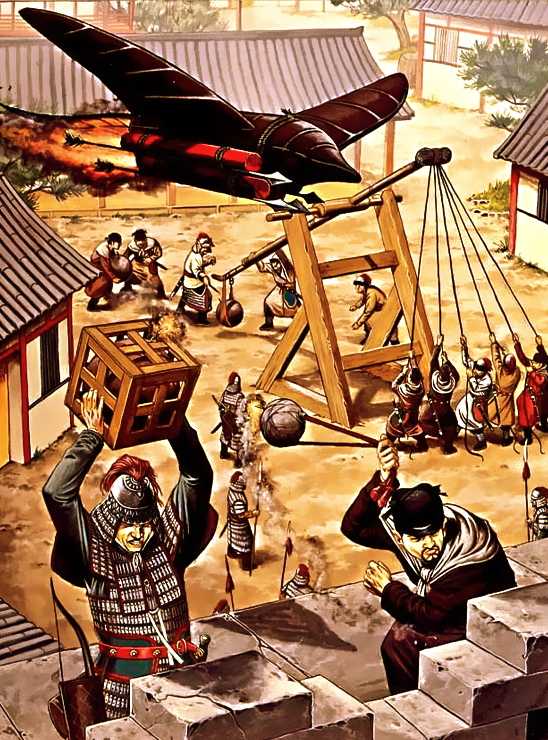

| Genghis Khan contemplated the transport of a quarter million

warriors from Lake Baikul over the ranges of mid-Asia into Persia. A

distance of two thousand miles direct, but the mountains he would

traverse would add many miles more. Each rider was to bring a string of four

or five horses. The Mongol "shock divisions" had their horses encased in

lacquered leather of red or black. Every cavalryman had two bows, and a

spare arrow case covered to protect from dampness. Heavy cavalry carried

a saber, axes hanging from the belt, and a rope or cord lariat. Tens of

thousands of Khitai's finest military formed their own divisions under

the "Master of Artillery". They were men skilled in building and working

the heavy siege engines, the ballista, mangonels and the dread Ho-pao

"Fire Gun" flame throwers. Many non-combatants were conscripted;

interpreters, merchants to act as spies later, mandarins to take over

the administration of captured districts, etc.

Rivers had to be crossed. The horses, roped together by the saddle

horns, twenty or more in a line, breasted the current. Sometimes the

riders had to swim, holding to the tails. Soon the rivers could be

crossed on frozen ice. "Even in the middle of summer," Ye Liu Chutsai

wrote of the westward march, "masses of ice and snow accumulate in these

mountains." Genghis Khan crossed the barrier during the height of

winter. |

|

Entering the western ranges beyond the Gate of the Winds, the

Mongols cut down tall trees, hewing out massive timbers to be used in

bridging the gorges. A quarter million men endured unimaginable

hardships in the utter cold of high Asia. When food failed they merely

opened a vein in a horse, drank a small amount of blood and closed the

vein. The horde moved west, scattered over a hundred miles of dangerous

mountain country, the sledges rolling in their wake, the bones of dead

animals marking their path.

By the time the first grass showed, they were threading into the last

barrier of the Kara Tau, the Black Mountain Range. The various divisions

closed up ranks, liaison officers galloped back and forth between

commands, the nondescript looking merchants rode off in small groups to

gather information. A screen of scouts were thrown before the divisions.

Through the forest scenery the Mongols could see below them the first

frontier of Islam, the wide river Syr, swollen by spring freshets.

Already the advance foragers were busy collecting supplies for the army,

by driving off herds, gathering grain, and incidentally, setting fire to

the frontier buildings. |

|

|

| Muhammad the Warrior was at the frontier even before the Mongols.

Recently victorious at war on the Indian subcontinent, the Shah

reassembled his army of four hundred thousand Turks, and organized his

Atabegs, and added divisions of Arabs and Persians. His spies carried to

him accounts of the approaching horde and he exclaimed, "They have

conquered only unbelievers. Now the banners of Islam are arrayed against

them."

The Shah deployed the mass of his army along the shores of the Syr

River, and moved up river with a contingent of about 30,000 men. In a

long valley with towering, forested cliffs on either side, Muhammad

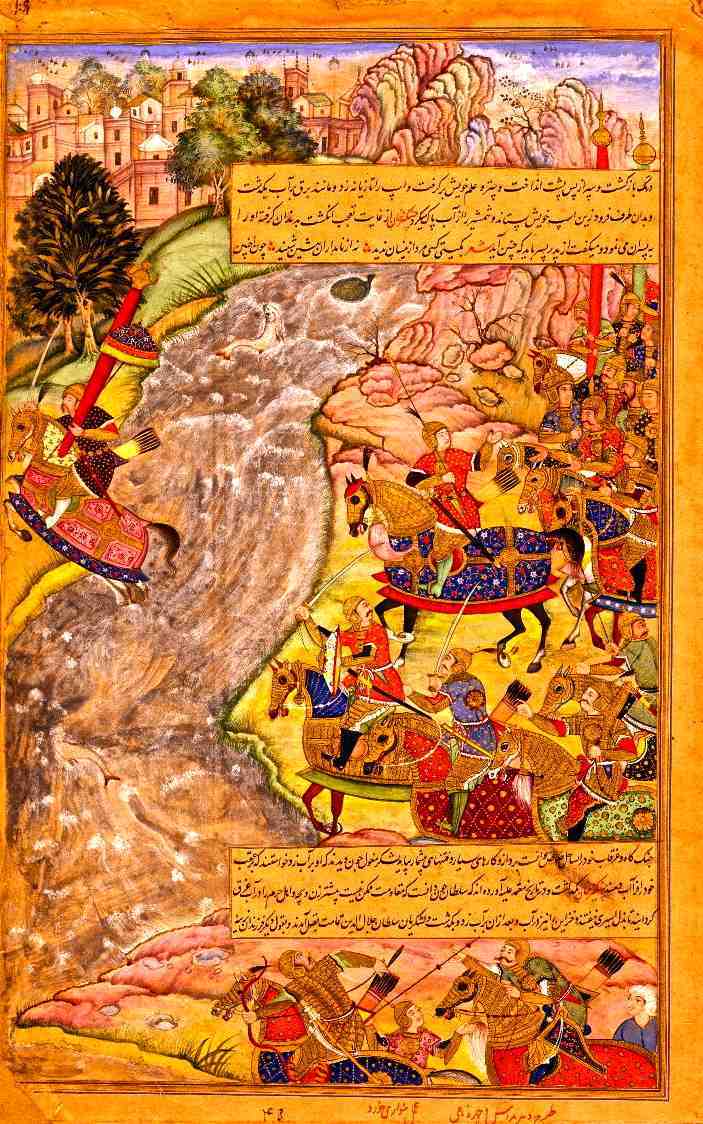

Shah's force met an approaching Mongol division. Juchi, first born son

of Genghis Khan commanded the tuman. The forces of the Shah were three

times the strength of the Mongol division. The Mongol general advising

the prince said to retire at once and draw the Turks to the main body of

the horde. The son of the Khan gave the order to charge. "If I flee,

what then shall I say to my father?"

First charged the Mongol Mangudai, or "God-belonging" squadron, the

pre-doomed "Suicide Squad". The shock cavalry units followed closely

behind. Heavy cavalry came next with swords in rein hands, and long

lances in the right hands. The lighter, faster squadrons covered the

flanks. At least three times as many Turks than Mongols lay dead at

day's end. The Shah himself, if not for desperate efforts of his elite

household divisions, would have been killed. The enemy hosts separated

for the night. |

Juchi |

| Sunrise found Muhammad the Warrior and his remaining squadrons in a

valley filled eerily with only the bodies of the slain. The Mongols had

vanished without a trace. In fact, the Mongols had withdrawn upon fresh

horses, hidden for this purpose, and completed a march of two days in the

single night. No longer did the Khwarezm Shah think of searching for

the horde in the high valleys. And a dread turned him back to his

fortified towns. Re-enforcements were called for from the south. The

Shah deployed his army on the western bank of the river Syr and awaited

the arrival of the horde, intending to give battle when the Mongols

attempted to cross the river. But the Shah did not realize the war was

now raging across a front of one thousand miles, as the Mongol divisions

descended from the mountain ranges at multiple locations. In the

mountain region a host so huge was forced to break into segments, each

wending it's own path westward, each under command of a veteran Orkhon.

Muhammad Shah, encamped behind the Syr, was unable to learn where the

Mongols were moving. Then came alarming news. Mongols had been seen

descending from the high passes two hundred miles to his right,

and almost in his rear. The Mongol tumans, under Chepe Noyon, had no

more than twenty thousand men, but the Shah could not know this, and

ancient Samarkand was directly in the Mongol path. Aroused by danger,

Muhammad split up half his army among the fortified cities. The Shah

then advanced the remainder of his host towards Samarkand. |

|

|

|

Even as these events transpired, two sons of the Great Khan had

appeared at Otrar, on the Syr, to the north. Otrar, whose governor had

put to death Mongol merchants. Inaljuk, who had ordered the executions,

was still governor of the city. In the great citadel of Otrar,

surrounded by the finest warriors at his command, in utter desperation,

they held out for five bloody months. Inaljuk, a man of war, took final

refuge in the highest tower and fought to the end, when the Mongols cut

down the last of his men. And when his arrows gave out he hurled stones

down on his foes. Taken alive, as a prize, in spite of total

desperation, he was sent to the Khan himself for judgement. Molten

silver was poured into his eyes and ears, the "Death of Retribution".

The walls of Otrar were razed to dust, and all inhabitants driven away.

While this was going on another Mongol force appeared at the Syr and

stormed Tashkent. A third detachment scoured the northern end of the Syr,

raiding the smaller towns. The Turkish garrison abandoned Jend, and the

people surrendered to the Mongols. The Turkish garrisons were massacred

by the merciless Mongols, but the city dwellers, mostly Persians, were

only driven out of the cities. But in one instance, where a Moslem

merchant envoy of the Khan had been torn to pieces by the men of the

town, the terrible "Mongol Storm" was begun. This is the attack that is

never allowed to cease. Without end, whether for days or months, fresh

warriors forever take the place of the slain, until the place was

carried, and it's people killed.

Genghis Khan never appeared along the Syr. The Mongol center had

vanished from human sight. Perhaps he made a wide circle through the Red

Sands Desert, because he appeared out of the barrens, marching swiftly

on Bokhara, from the west. Chepe Noyon was advancing from the east,

Genghis Khan was moving in from the west, and the Shah at Samarkand

might well feel that the jaws of a trap were rapidly closing in upon

him. |

| The Mongol tumans under the sons of the Khan, spreading fire, death

and fear along the Syr River, had been no more than so many masks, for

the real attack was by Chepe Noyon and Genghis Khan, advancing on

Muhammad the Warrior at Samarkand.

Genghis Khan moved quickly upon Bokhara, a stronghold of Islam,

honored by many an imam and sayyid, the savants of Islam. It was a city

of academies with gardens and pleasure houses. The Turkish officers

chose to abandon the inhabitants to their fate and escape to join the

Shah. The elders of the city, judges and imans, consulted together and

went out to yield the keys of the city. Genghis Khan promised to spare

the lifes of the citizens.

As the Mongols looted the granaries and storehouses, Genghis Khan

rode to the city square where orators were accustomed to assemble an

audience to lecture upon matters of science and doctrine. Here, from the

high speakers rostrum, in his black lacquer armor and leather curtained

helmet, he addressed the crowd of mullahs, scholars, and common people

of Bokhara.

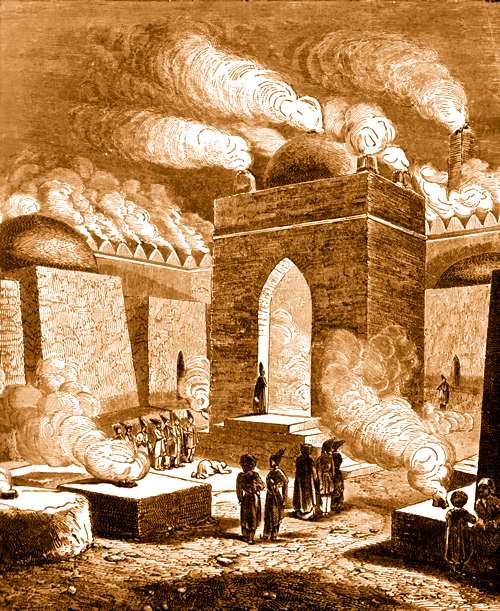

The Moslems saw the Mongols as the "Anger of God" descended upon

them. Genghis Khan, master of fear, deception and strategy, fanned the

superstitious dread of the Muhammadans from this sacred Islamic pulpit.

First he commented gravely that it was a mistake to make the pilgrimage

to Mecca, "For the power of Heaven is not in one place alone, but in

every corner of the earth."

"I am the wrath and flail of Allah," he told them. "The sins of your

emperor are many," he assured them. "I have come to destroy him as other

emperors have been crushed. Do not give him protection or aid."

Genghis Khan only spent two hours in Bokhara, hastening on to seek

the Shah in Samarkand. Different areas of the city had been fired and

the flames spread a pall of smoke rising over the city as the Khan rode

out. The captives were driven toward Samarkand, and being unable to keep

up with the Mongol horsemen suffered terribly during the brief march.

Mighty Samarkand was the strongest of the Shah's cities. The defenses

were formidable. High walls and twelve iron gates flanked by towers.

Twenty armored elephants and one hundred and ten thousand warriors,

Turks and Persians, had been left to guard it. |

|

| With no more than his own attendant nobles, his elephants and camels

and household troops, Muhammad the Warrior left Samarkand. The Shah took

with him his treasure and his family. He intended to return at the head

of a fresh army.

Genghis Khan said, "The strength of a wall is neither greater nor

less then the courage of the men who defend it."

The swift, methodical preparations of the Mongols alarmed the Moslems

at Samarkand, who beheld in the distance the vast multitude of captives,

and assumed the horde was much larger than it actually was. The

Turkish garrison sallied out once and was drawn into one of the usual

murderous Mongol ambushes, and fared poorly, taking great losses. The

imams and judges went out and surrendered the city the following day.

Thirty thousand Kankali Turks on their own account went over to the

Mongols, were received amiably, given Mongol military dress and

massacred a night or so later. The Mongols would never trust the

Khwarezm Turks, especially those who turned traitor. |

Khwarezm Shah Escapes Genghis Khan |

Not having found the Shah at Samarkand and hearing the story of his

flight, Genghis Khan called for his Orkhons Subotai and Chepe Noyon. He

ordered them, "Follow Muhammad Shah wherever he goes in the world. Find

him alive or dead. Spare the cities that open their gates to you but

take by assault those that resist. I think you will not find this as

difficult as it seems." They were given two tumans, twenty thousand men.

Every man of the two picked divisions had several horses in good

condition. They could cover eighty miles a day, changing to fresh horses

several times a day, and only dismounting at sunset to eat cooked food.

It was then April, 1220, the Year of the Serpent, in the calendar of the

twelve beasts.

Picking up the trail they followed the caravan route west toward the

Caspian, and scattered remnants of the Shah's armies fleeing the Mongol

terror. Near modern Teheran they met and defeated a Persian army, thirty

thousand strong.

Muhammad Shah had sent away his family and hidden his treasure, and

the numbers of his attendants and soldiers decreased each day. The

Mongols eventually found the treasure and almost caught him at Hamadan.

His men were scattered and ridden down. The Shah escaped, but some of

his Turkish warriors were rebellious. The wary Shah slept in a small

tent next to his own. One morning he found his own empty tent filled

with arrows.

"Is there no place on earth," the Shah asked an officer, "where I can

be safe from the Mongol thunderbolt?"

He was advised to take ship upon the Caspian to an obscure island

where he could be hidden until his eldest son, Jalal ed-Din, a favorite

of the Khwareszm army, could gather a host powerful enough to protect

the Shah. This Muhammad did. Disguising himself, and with only a few

nondescript followers, he passed through the gorges, seeking a small

town he remembered on the western shore of the Caspian Sea. It was a

tranquil place of fisherman and merchants. But the Shah, a man of ego,

though weary and ill, deprived of his court, his slaves and cup

companions, would not sacrifice |

| the prestige of his name. He insisted on reading the public prayers

in the mosque, and his identity did not long remain a secret. A

Muhammadan, who had suffered oppression at the hand of the Shah,

betrayed him to the Mongols who had scattered another Persian army at

Kasvin, and were questing after the Shah through the hills. They rode

into the town that had sheltered him, as he was preparing to board a

fishing skiff bound for his island sanctuary. Arrows were given flight,

but the boat drew away from the shore and some of the nomads in their

rage actually urged their horses into the water. They swam after the

skiff until the strength of men and beasts gave out and they disappeared

in the waves. The Khwarezm Shah, called Muhammad the Warrior, Overlord

of Islam, weakened by disease and hardship, died on his island, so

poverty ridden that his only shroud was a shirt off one of his last

followers. |

|

While the two divisions were raiding west of the Caspian

Sea in close pursuit of the fleeing Shah, two sons of the Khan journeyed

to the other inland sea, called the Aral. There they followed the wide

Amu River to the native city of the Khwarezms, Urgench. The Mongols

settled down to a long and bitter siege, in which, lacking large stones

for their casting machines, they hewed massive tree trunks into blocks

and soaked the wood until heavy enough for their purpose. |

| The desperate hand to hand fighting, once the walls were breached,

lasted within the city for a week. No garrisons abandoned this citadel

of fighters. The chronicles say the defenders used Flaming Naptha, a new

weapon that had been used with devastating effect against the crusaders

from Europe, the knights of the cross, in the Holy Land. Urgench

eventually fell, but Jalal ed-Din, the valiant son of the defeated Shah,

escaped to lead fresh forces against them. When the Mongols abandoned

the site of a city they trampled and burned whatever crops might be left

standing so that those who escaped their swords would soon starve to

death. But at Urgench, where the long, grueling defense had made the

Mongols suffer much, they actually went to the engineering trouble to

dam up the river above the citadel, altering it's natural course, so it

flowed over the debris of houses and walls. This abrupt changing of the

course of the Amu River puzzled geographers and scholars for centuries.

|

|

|

| Genghis Khan was quite aware of his situation. He knew the real test

of strength was before him. He faced a Moslem Jihad, a holy war was

brewing. Perhaps a million men, good horsemen and exceedingly well

armed, were preparing to move against him. They mustered under their

natural leaders, the Persian princes and the sayyids, the descendants of