| |

|

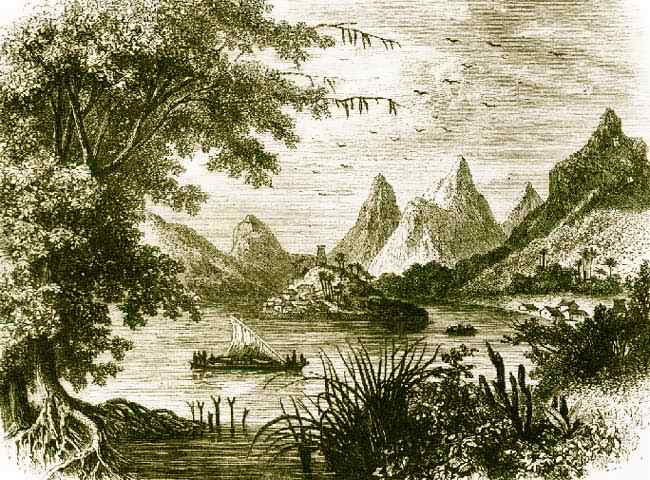

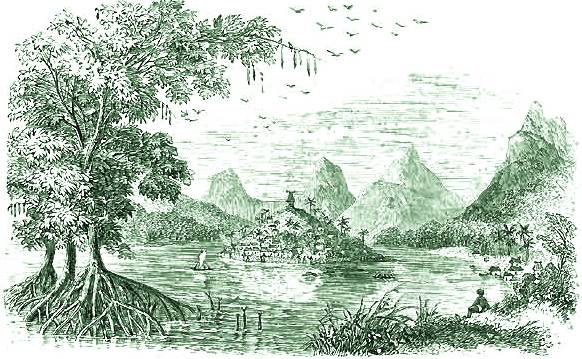

Fiji Coastal View . . . circa 1849 |

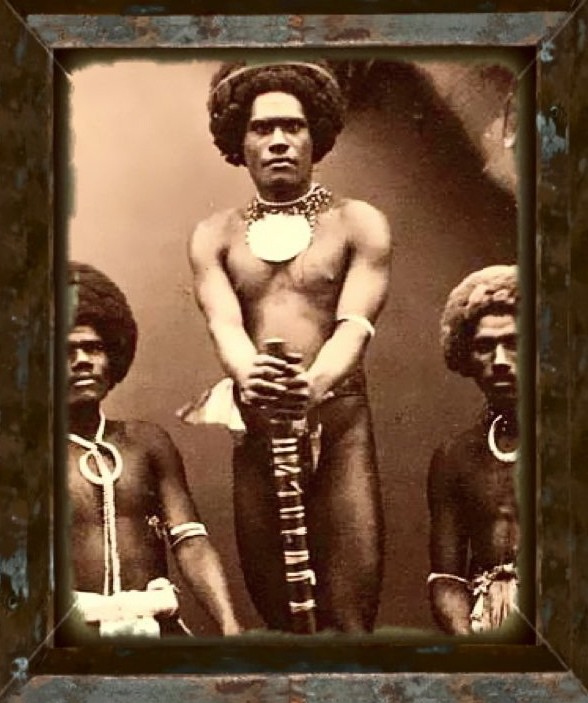

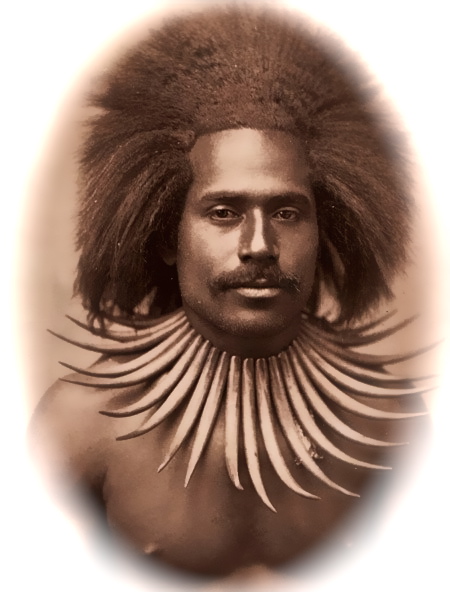

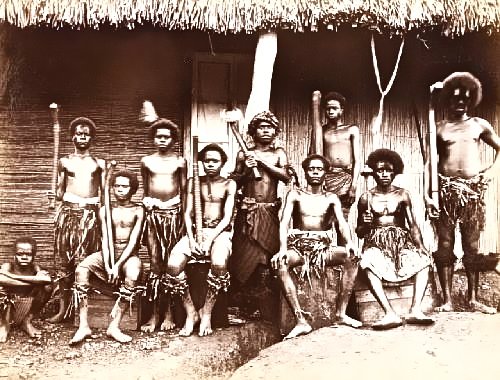

Fiji Islands - South Pacific Ocean |

|

Warfare was a base of Fijian Society

Fighting was literally a 'Way of Life' in old Fiji |

|

"Ships going their I would recommend to go well armed &

niver to be of their gard for althow they are a hospitable people yet

they are Canables & will take every Advantage from their propensity to

stealing, the low class of them in particular. I would recommend never

to go on shoar without being armed for though you may be very friendly

with those you are trading with yet they are always at war among

themselves and those that are their Enomies will be yours"

William Lockerby - Directions for the FeeJee Islands, 1810 |

|

Fiji, beginning of the 19th century, few people lived to die of old age,

and men, quite literally, never dared to move about unarmed. Distrust

and suspicion, fear of attack and murder, these were a part of daily

living. The sight of a strange canoe made people uneasy, and women and

children would often flee for their lives at the sight of a stranger.

Assassination amongst men was always lurking nearby.

Fearing assassination, when meeting in a house around the Kava or

Yaqona bowl, men customarily left their weapons just outside the door so

that they could relax confident and safe in each others company. But one

Tui Nayau was clubbed dead while drinking Yaqona. The assassin had his

pole club smuggled into the house by his little daughter wrapped in a

fresh unfurled plaintain leaf, the child crying and asking for her

father, to gain admittance to the house. Sneak raids and murderous

ambushes were a common and constant threat. If the enemy were taken by

surprise, where attackers secretly entered and stormed a town, these

stealth attacks could result in quite large scale massacres, with

casualty rates entering the scores and even hundreds.

Larger wars or "state wars" between confederated chiefdoms tended to be

more openly conducted, war being formally declared with armies marching

to attack fortified towns. Larger still, "widespread wars" involving

several confederations of tribes or states and covering large land

areas, often dragging on for months with thousands of warriors afield.

In some wars, battle and especially massacre casualties climbed into the

hundreds and on rare occasions into the thousands. |

| The most serious and destructive conflicts were those between large

scale tribal confederations or states under high chiefs who were bitter

personal enemies. They involved armies in the thousands of warriors, and

resulted in the sacking and depopulating of large land areas and even

entire islands. Sometimes these conflicts continued until one of the

high rival chiefs was cut down or fled into exile, in which case

plotting vengeance and living to fight again when the opportunity

offered. |

|

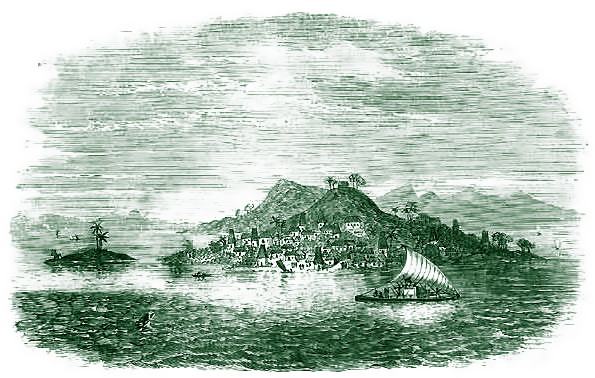

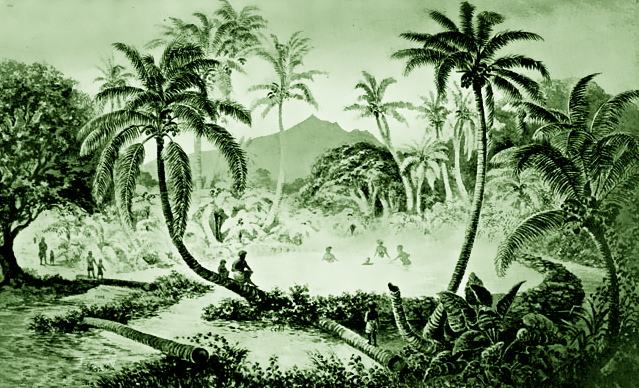

Bau Island City . . . 1855 |

|

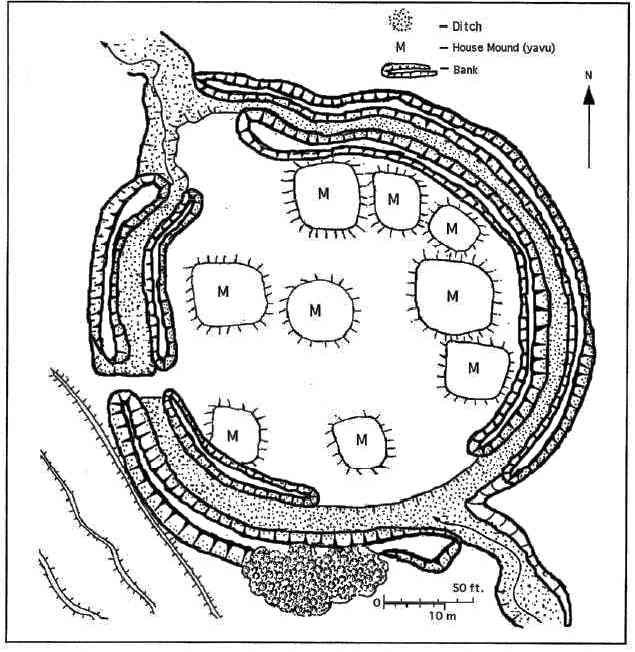

"Their villages were mostly perched on the most

inaccessible peak and precipices. These eyries were skillfully fortified

with palisades and galleries for sharpshooters, which, with their well

chosen strategic position, rendered some of them traditionally

impregnable, and until the introduction of European firearms of

precision . . . . they were never taken. I have seen fortified places on

a plain so surrounded by moats, where the mud was armed with stakes and

split bamboos, and so encompassed with clay ramparts and stout

palisades, line within line, that the very taking of them in purely

native warfare was a very tedious or very fatal undertaking. I saw one

village, called Waini-makutu, where the stream had been most ingeniously

diverted into the circular moat, in which it was swirling round the town

on its onward progress, and thus forming a perpetual defense of the

people. An officer of the English army, who had taken some of these

forts of the hillmen, expressed to me his surprise at the skill and

science of engineering they displayed. Covered galleries and lanes, and

curious platforms for sentinels and marksmen, were also features of

these works." - Reverend A. J. Webb . . . 1890. |

By no means were all Fijian forts circular and ditched. Forts in

more rugged country took every advantage of the difficult terrain. They

were built along razor back ridges and on cliffed and virtually

unscalable crags with formidable natural defenses. Some such positions

so strong that a handful of determined men could defy an attacking host.

On even the strongest such natural fortifications however, the defenses

were strengthened by scarping or digging out natural slopes to steepen

them, and the excavating of war-ditches across ridges, and building

artificial defensive terraces. The terraces fronted by fighting fences

on steep slopes. Also, the erection of earthen banks, loopholed loose

stone walls and fighting fences at weak points.To take the forts

required the storming of barricade after barricade and running into

ambuscade after ambuscade. |

|

| Among other hazards to be faced when assaulting hill forts were the

big rocks and boulders which the defenders dropped and rolled down on

their assailants. Sometimes these were lashed in strategic positions

with vines, the defenders only having to slash the vines to send the

boulders crashing down on their enemies. |

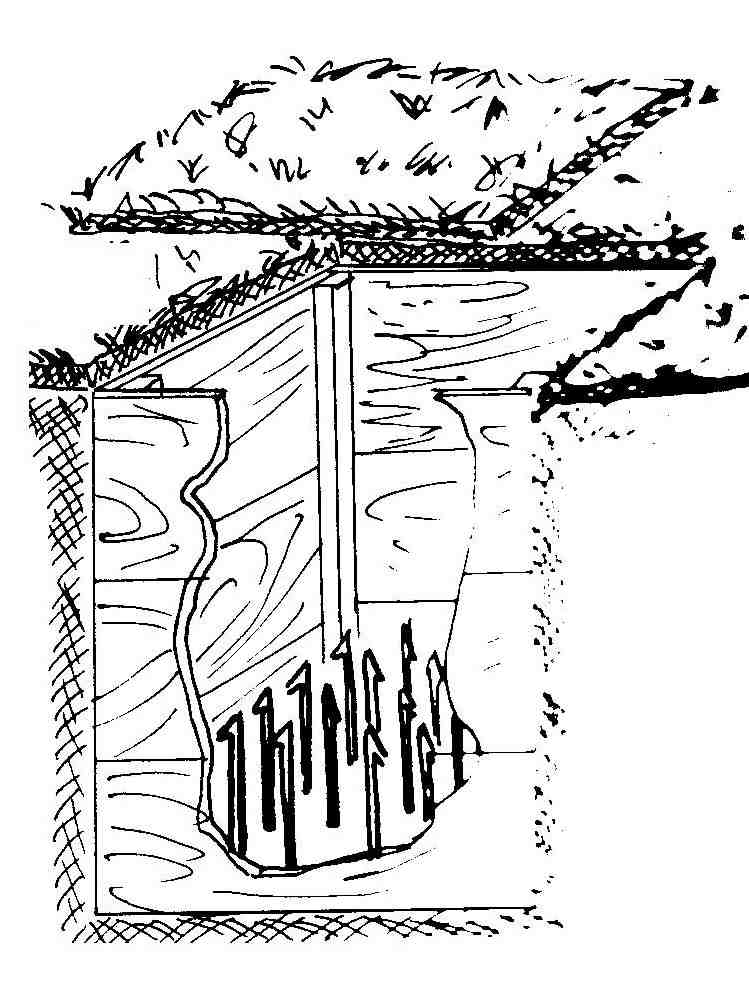

Unpleasant obstacles about Fijian fortifications were the pitfall

man traps called Lovosa, which incapacitated or killed a warrior.

These were set in both gentle and rugged country along paths and

approaches the enemy was likely to traverse, and in gardens he would

plunder. When a retreat was anticipated they would set the in the fort

itself, as a parting surprise for the enemy.

The Lovosa pit fall trap was typically a small hole dug, in the

bottom of which were planted one or more upward pointing hardwood spikes

or skewers of split bamboo, called Soki. The mouth of the pit was

camouflaged twigs covered with turf, leaves or grass.

Larger and deeper Lovosa into which men fell headlong to impale

themselves on the stakes they contained were also used, but to a lesser

extent.

As defenders retreated into the fort, in order to render the forcing of

the gate more dangerous, the Fijians employed calthrops

consisting of a variety of small sharp spikes called Soki, which

were stuck upright in the ground. These Soki were baked and

hardened, and then poisoned. The Soki were usually slivers of

split bamboo or sharp hardwood spikes, or the barbed tail spike of the

stingray, also broken glass, were all used. Each Soki was cut or

charred part way through where it protruded from the earth to encourage

it to break off in the foot.

The Soki were also placed in the narrow stream channels leading

through Mangrove swamps to hinder the enemy, wound his scouts and

generally delay his advance. |

|

|

Fijian Fortifications Diagram |

"These are the days of education, and in their way the Feejeens are

on the alert: they rub human flesh over the lips of their children, and

put a portion into the infant's mouth, that it may be nourished by its

juice and trained in the practice of cannibalism!"

Reverend Walter Lawry . . . 1850Fijian children grew up against a

violent and bloody background. They grew up in a land where killing was

glorified and common place. They received ample psychological and

physical training to take their places in a society geared towards

warfare. War, with its bloodshed, cannibalism, and violent Gods was a

natural state for them from infancy onwards. Their histories and legends

extolled the martial deeds of their heroic warrior forefathers. |

|

|

Children's games naturally reflected the society they grew up in and

often centered on war and cannibalism. Quote Reverend John Hunt . . .

1858, "It is particularly painful to see them acting a cannibal feast.

One of them will feign himself dead, and the others carry him about,

singing the cannibal song."

Children orphaned by war or murder were encouraged to nurture vengeance,

being disparagingly known as 'the children of the dead' until they grew

up and paid back their parents deaths in blood.

Children practiced on each other with bows and arrows of cane without

hardwood points, but instead a cushion of "Tapa". Through such games and

more formal training by their fathers, boys became skilled in the

various Fijian weapons, and in the equally important art of dodging the

clubs, spears and arrows of the enemy.

Rough mock battles (particularly fights with Vudi stalk coconut frond

midrib clubs) continued until manhood. The youths of a town often

challenging their visitors or neighbors to such competitions, which were

known to end in lost tempers and broken limbs.

More realistic training occurred on the battlefield. Boys accompanied

the army to carry extra weapons for the warriors and to help in

dispatching the helpless enemy wounded, as well as mutilating the dead.

When a large number of enemy children were captured, they were sometimes

brought home alive so that the boys of the victorious tribe could have

some live practice, shooting them, spearing them with their scaled down

weapons or clubbing them to death. |

The Fijian warrior did not rely on a shield or armor, but depended

rather on his well developed agility and alertness. Games taught

accuracy in throwing and an agility in dodging, applicable to the

throwing club or the spear. In one game teams of men or boys, supplied

with citrus fruit, stood one to one at 20 meters both throwing and

dodging until a hit signified a kill. This until one side was wiped out.

Bushcraft and further accuracy were learned on pig hunting excursions

with their fathers and on their own hunting. The Fijian warrior absorbed

in his youth the stealth and bushcraft which were to serve him well as a

warrior in later life, using ambushes as his specialty. The warrior had

to be alert, for example, to the harsh alarm squawks and rattles of the

large Parrots, which might indicate hidden human presence in the bush

nearby. Then again, noisy and static presence of a number of these birds

about the track ahead almost certainly indicated an ambush party was

lurking in the undergrowth.

A tally of kills made with a war club was often kept by means of

nicks or notches on the head or handle, or by boring small holes in the

shaft, another common method being to inlay a tooth from each victim in

the club's head.

In Fiji, a youth could only obtain true warriors status by killing an

enemy with a war club as distinct from all other weapons. A coward whose

club was still unstained with blood at the time of his death was doomed

to pound human excrement with his dishonored weapon in Balu, the

afterworld, onward into eternity. |

|

|

Particularly bold and stealthy were the Lone Warriors

known as "Bati Kadi"

Translated 'The Teeth of the Black Ant'

Those who infiltrated the enemy line by night to silently slay

both sleeping foes and drowsy sentinels

|

|

|

| Fijian war could be extremely deadly. In addition to the massive

wound trauma inflicted from the weapons, the Fijians used vegetable

poisons on their arrows. "There are many independent towns, and

especially in the interior, of which nothing more than their names is

known by the people on the coast."

Reverend John Hunt . . . 1858

Many remote and particularly violent hill tribes of the larger islands

were laws unto themselves, with the bolder tribes raiding almost at will

then retreating into their mountain fortresses, where none dared pursue.

"In native fighting, fences were thrown up by the attacking party,

starting at long distances from the village to be attacked and making

slight advances and fresh fences at intervals of days or weeks. In some

cases it might be months before any actual assault was made. The

attacking party might return home, neither party having come into close

conflict. Numbers of people were at times slain by parties out for food

or skirmishing round. In all fighting the attacking side ravaged the

country for food belonging to the enemy, and according to the quantities

of food, so the duration of a fight might be determined." - Georgius

Wright . . . 1916

As an attacking army advanced on their fortifications, the defenders

usually ventured out long distances to obstruct them, skirmishing,

ambushing and, if unsuccessful in stemming their advance, gradually

falling back on the defensive works.

Both sides sent out scouts far ahead of the main body to ascertain

enemy strength and movement, while friendly chiefs secretly passed on

military information. |

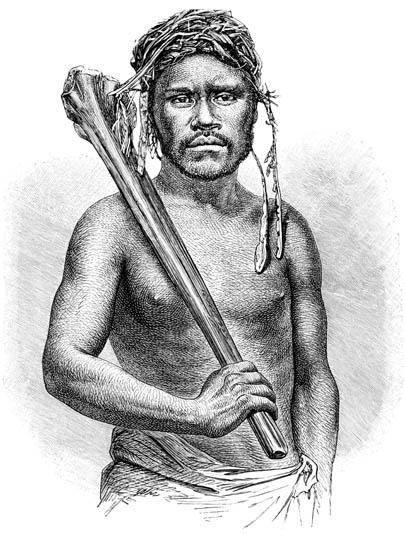

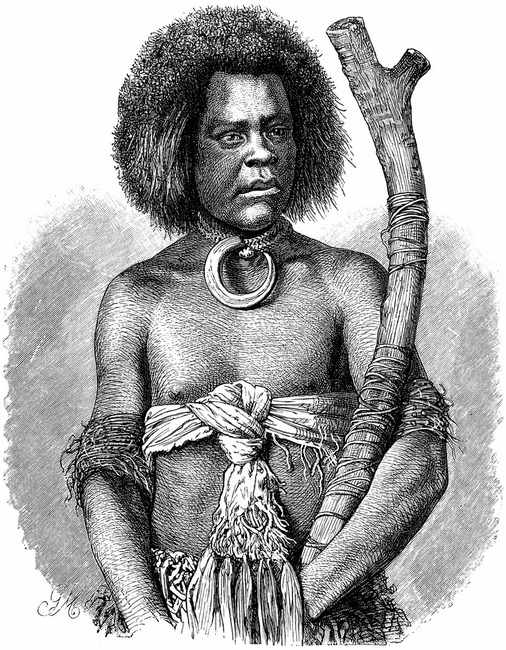

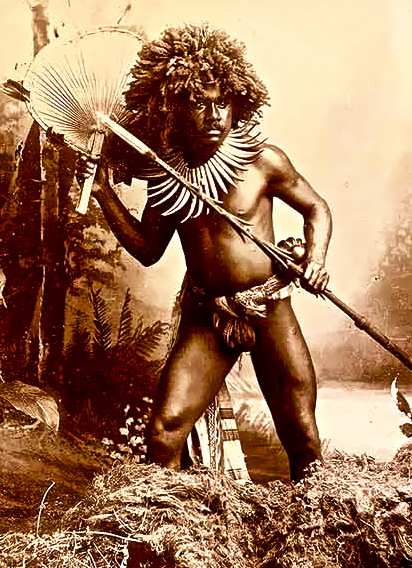

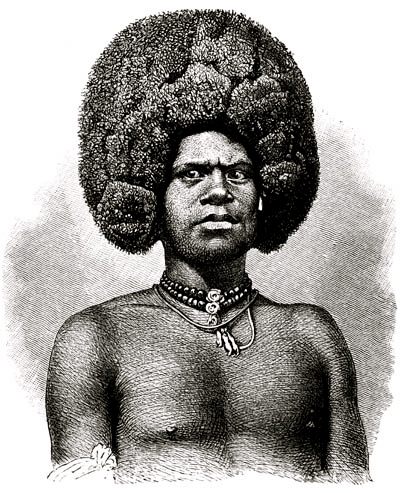

Colo Highland Warriors |

|

|

Each contingent of allies camped separately in its own

individual field encampments, under the command of hereditary chiefs.

In attacks on strongly fortified positions individual warriors made use

of all available cover as they came within effective sling, bow or

musket shot range. The battle usually initially consisting of back and

forth sniping at extreme range. The defenders would pour out showers of

arrows, sling stones, spears and musket balls, with the women and

children joining in with bows and arrows. The defenders frequently

sallied out on the offensive, often sending the attackers running for

their lives. Back and forth chases were typical of these sallies and

counter attacks, the fighting splintering into a series of single

combats with the warriors hewing at each other with clubs and battle

axes.

Sometimes, however, two large groups of warriors clashed head-on at

close quarters and heavy casualties were caused in a few minutes of

vicious hand to hand fighting with clubs, spears, battle axes, throwing

clubs and clubbed muskets, with warriors on the outskirts sniping into

the melee with bow, sling or musket. Some of these hand to hand fights

were savage to the extreme, and over the din of shell battle trumpets,

shrieks, musket shots, clash of club on club, and crunch of club on

bone, rose the war cry of the warriors as they killed. Each clan having

its own distinctive local killing war chant.

The classic Fijian ambush tactic on a grand scale was the Cuka-ni-valu,

translated 'the fishing net of war'. In short, ambush by encirclement.

The ambushing force hid in the bush in a large U, about a track likely

to be used by the enemy. |

| The battle line forming the base of the U lying across the path,

while the wings of the U lay some distance back, paralleling the path on

either side. Ideally, the enemy column marched unsuspectingly into the

open end of the U, and ran up against the battle line forming its base,

which engaged it as the two flanking wings rushed down on either side

with their ends closing in to cut off the enemy column as it retreated.

|

Viti Levu Highlands . . . circa 1881 |

In war, it was always the duty of the women, assisted by the stoutest of

the boys, to feed the warriors. They supplied all the delicacies of the

sea coast including fish, cockles, native lobsters, coconut and taro

puddings, etc., and they willingly and cheerfully endured the hardships

of the campaign.

The women also played a useful support role in the actual fighting

sometimes. They assisted by stationing themselves on prominent hills and

calling down information on the enemy movements, to their warriors and

sometimes luring the enemy into an ambush. Like the boys, the women

finished off enemy wounded.

If a town was taken by force or an army routed afield, the survivors

fled for their lives in panic, with the enemy in full homicidal pursuit.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

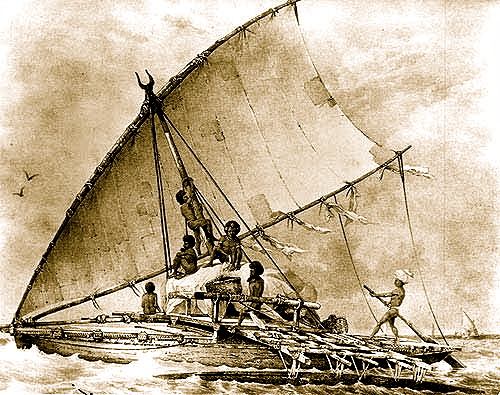

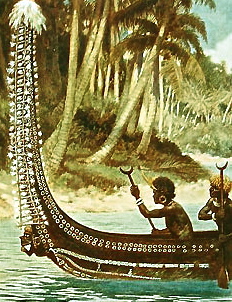

Fijian Outrigger Sailing Canoe |

Warfare at Sea

Invading Fijian armies often traveled long distances to

wage war, being transported from island to island by canoe. A fleet of

war canoes and the warriors transported by it were known as a "Bola",

the Fijian term for a hundred canoes.

Small and quite large scale sea battles were commonly fought. Some of

these sea battles involved large vessels big enough to be regarded as

full blown naval engagements. Most numerous, however, were murderous

incidents involving small canoes in petty warfare.

In the ambush tactic known as "Waqa-ubi" warriors lay hidden in a canoe,

which was allowed to drift ashore as if derelict, and then they sprang

out to attack their enemies, who were coming down to secure the craft.

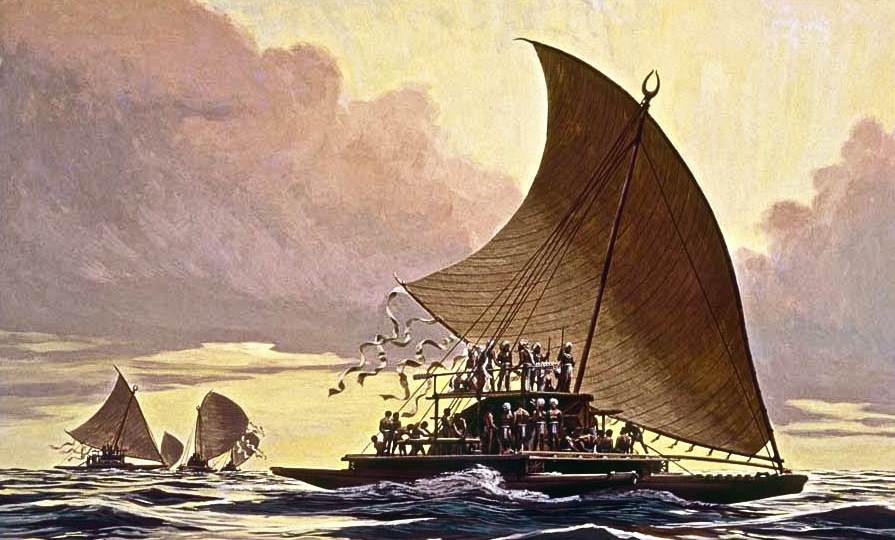

The huge, plank built, double-hulled "Drua", some of

which exceeded thirty meters in length, were capable of carrying large

contingents of warriors, in addition to their sailor crews, with the

largest Drua carrying in excess of 250 passengers on deck.

|

|

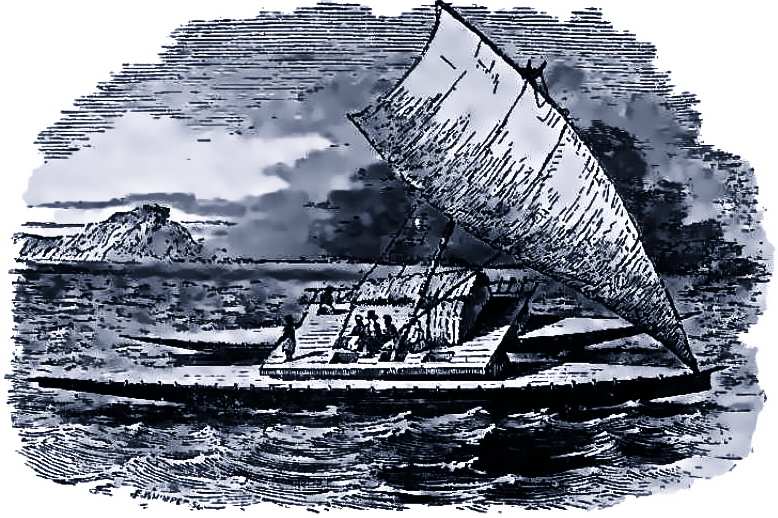

Fijian Double Outrigger Canoe |

The huge, plank built "Camakau" outriggers could also transport

large numbers, as could the larger of the "Tabilai" fighting canoes,

which were either double-hulled like Drua, or had a single hull and an

outrigger like Camakau, the ends of the hulls having been modified by

being thinned down, with a meter and more of solid wood left at each end

to allow for more effective ramming.

The basic battle tactics were to run down and attempt to ram an enemy

canoe amidships to sink or disable her, the warriors in the latter case

boarding to fight hand to hand. Another tactic was to maneuver to

windward of the outrigger hull of the enemy canoe and try to cut through

the rigging, dropping her heavy sail and yards crashing onto her crew

and warriors, entangling and engulfing them, whereon the attacking

warriors boarded to club, spear and shoot them through the sail.

As the enemy canoes drew near each other they exchanged showers of

arrows, sling stones, spears, bullets and occasional cannon balls. |

| The warriors next boarding as they closed to fight with spears and

clubs in a fierce melee, which often ended in the wiping out of one of

the crews, unless they were able to swim ashore or to a friendly canoe.

Survivors were mercilessly shot and speared in the water as they swam

for their lives. Cannon were widely used aboard large canoes in running fights and to

bombard shore positions. The Drua and other large canoes were engaged

and even taken by attacking swarms of smaller canoes. |

|

Fijian Drua |

|

|

There were a myriad of Gods in old Fiji - for every

locality had their own Gods

One of the better known War Gods was "Cagawalu the Great" of Bau

Cagawalu stood ten fathoms tall! |

|

The War Gods sanctioned and demanded

both war and human sacrifices for religious purposes! |

Fijian religion was inextricably mixed with war and cannibalism. It

developed over hundreds and possibly thousands of years of warfare and

was admirably suited to the needs of a martial society. Like many other

religions it was a major cause of bloodshed.

Quote the Reverend John Hunt, 1858, ". . . . it must be lamented that

their worst crimes are sanctioned, and are continually promoted, by

their divinities, who are not only cannibals and adulterers like

themselves, but have pleasure in those that are such." |

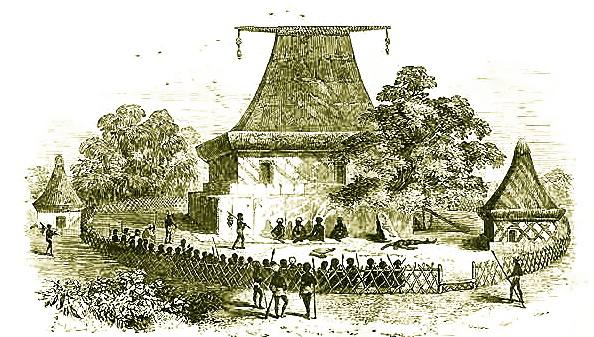

Fijian Temple |

Hatred was carefully nursed and kept smoldering in songs and prayers

and by personal sacrifice, so that when the opportunity for vengeance

came, the Fijians were quick to seize it. Revenge did not stop with the

killing of the enemy, but was, along with religion, principle forces

behind Fijian cannibalism. Before embarking on a raid or war the

Fijians conducted religious ceremonies, and consulted the Gods in an

attempt to insure success in the campaign, and in some cases, to render

the warriors invulnerable to the weapons of their enemies.

"God Houses" or Bure Kalou had interiors that often resembled

armories, with rows and bundles of spears stacked in the rafters, and

muskets, bows and arrows, war clubs, and throwing clubs hung about the

walls. All weaponry coated glossy black with the soot from the fire kept

constantly smoldering, and often eerily festooned with cobwebs. |

Cannibal Temple Bau Fiji |

Some of these weapons had been presented as offerings made to the

Gods when consulting them through the medium of the Priests, or they

were weapons of deeper religious significance, having killed enemies and

been presented to the War God to ensure his protection against enemy

weapons in the future. For instance, a warrior might present a spear

with which he had killed, and so gain the War God's protection from the

spears of his foes. The weapons stored in Bure Kalou seem

generally to have been regarded as Ka-tabu or sacred objects that

ordinary people did not handle, and thus they hung untouched for year

upon year. But some spears from Bure Kalou were used in combat.

These were more prized the older they get. Glazed with smoke and dirt,

and consecrated by the War God, wounds from these spears are certainly

fatal, while the same kind of wound from a new spear or one kept by it's

owner, will heal.

For at least several days before a fight the warriors usually

abstained from sexual relations in an attempt to insure the success of

the expedition. Religious ceremonies were conducted under the direction

of a priest to make the warriors "Vodi" or invulnerable. |

|

|

"Cannibalism among this people is one of their

institutions; it is interwoven in the elements of society; it forms one

of their pursuits, and is regarded by the mass as a refinement."

Reverend Thomas Williams . . . 1884 |

|

Sanctioned and indeed demanded by Fijian religion,

cannibalism allowed revenge and vindictiveness to be carried past an

enemies death. Some of the principal chiefs and priests of Fiji were

fond of human flesh to the point of addiction, but in being so were

serving their religion and society. |

|

|

If the war or raid had been particularly successful,

Manumanu-ni-laca consisting of living or dead enemy children swung

in baskets or by their heels from the sail yards of the canoes as

victory banners. Nearing home shore, to broadcast that they had killed,

long poles repeatedly splashed the water, and the warriors singing and

dancing the "Cibi", Death Dance, while the Lali slit drums

thundered out the "Derua" Death Beat.

At the outskirts of town came the lewd Dele or Wate dance

by the women, who, appearing naked in public upon this occasion, and

bringing into the open and heightening the tensions of the sexual

undertones, which keep cropping up in Fijian warfare. Erskine . . .

1853, describes for us, "I saw that their animosity was so great, that

they did not consider the enemies being killed and eaten sufficient to

gratify their revenge, without deriding and degrading them as it were,

after death, which the young girls were doing in a lewd kind of dance,

touching the bodies in certain nameless parts with sticks as they were

lying in a state of nudity, accompanying the action with words of the

song. I found out afterwards that the opposite sex were always selected

for the purpose of making the disgraceful end of their enemies

notorious."

Before the Temple the warriors flung the bodies at the feet of the

principal chief and reported their exploits. The chief thanked them and

ordered the priests to present the bodies to the War God. Having been

offered to the War God, the heads of the bodies were shattered against

the Vatu-ni-mena-mona, the "Braining Stone" column set

upright in the ground outside the Temple, thereby sacrificing the brain

to the appetite of the God of War. |

| Feelings ran high while the flesh was slowly cooking, the warriors

doing their Death Dance, the women the lewd Wate, until the tension was

broken in a frenzied sexual orgy. Normal social restrictions broke down

for the night. Women were copulating with warrior after warrior in a

scene the European eyewitnesses could only hint at, although stressing

its licentious nature.

An anonymous European beachcomber relates witnessing a particularly

wild orgy in 1809, "That night was spent in eating and drinking and

obscenity the blood drank and the flesh eating seemed to have a

maddening effect on the warriors. I had often seen men killed and eaten

but I never heard or saw such a night as that. Next morning many of the

poor women were unable to move from the continuous connections of the

maddened warriors."

Armies and war parties in the field generally ate the flesh of enemy

bodies or Bokola, as bodies destined for the oven were called. With a

minimum of ceremony and ritual, the mutilated corpses were cut up,

wrapped in Vudi plantain leaves, and cooked in pit ovens or Lovo.

Concerning one of the great Viti Levu cannibal chiefs, circa 1827,

William Mariner said, "He was not in the habit of sacrificing his

prisoners immediately, (finding them perhaps too tough for his delicate

stomach), but of actually ordering them to be operated on, and put in

such a state as to get both fat and tender, afterwards to be killed as

he might want them. |

|

|

Fijian Warriors . . . carrying

Victim |

|

|

A tally of kills made with a war

club was often kept by

Nicks or notches on the head or handle

Boring small holes in the shaft

Another common method being

Inlay a tooth from each victim into the clubs head |

|

The Pacific is the tribal club center of the world and there is a good

and practical reason for this. Hardwood trees were abundant in most of

the Pacific, while iron was virtually non-existent before the late 18th

and early 19th centuries. A Fijian war club was the most cherished weapon of the Fijian

warrior. It was designed and made for specific purposes and there are

approximately thirty distinct and diverse types of native weapons used

by the Fijians.

A club used to kill many enemies was believed to have a life power of

its own or Mana. A Fijian War club with large amounts of Mana were

sometimes placed in a temple to the gods of war, and became ritual

objects in funerary rites and certain craft ceremonies.

Clubs are aggressive, one-on-one offensive weapons requiring skill,

strength, speed and agility, and this fits both the Polynesian idea of

waging war and their concept of individual worth. In Polynesia, war was

an activity fought between groups, but waged by individuals, each

seeking to prove his personal prowess. As a result, the competition for

fame and Mana (personal charisma and power) within the Polynesian

warrior class was intense. It was quite a common, for example, for Maori

war leaders to fight one on one duels as proxies for their armies, and

there were complex rules for these jousts.

In fact, the Polynesians had elevated club fighting to an art form, and

young boys in Fiji, Tonga, Samoa and New Zealand spent hours mastering

the arm, body and foot moves necessary to use various types of club

effectively – skills their lives would depend on.

Of all the Polynesian people, the Fijians were the most prolific club

makers. They had perfected the art of growing clubs by tying young |

| branches at right angles to the trunk so that they could be

harvested as L-shaped billets with a short, thick arm to form the head

of a club.

They also delighted in producing many different types, often with a

specific function in mind. The totokia, for example, had a long point

at the end of the head which could be used to neatly pierce a hole in an

opponent’s skull once he had been felled by the broad side. Each Polynesian culture had its own favored style of warfare and

produced the clubs required to execute it. The Fijians were experts at

all types of club warfare, and are well known for long clubs whose

heads had sharp edges – real bone breakers – but they are perhaps best

known for the short ulla or round headed throwing club. Each Fijian

warrior would go into the fight with three or four tucked into his belt.

Some clubs had a very bloody career before being hung, much notched, in

the Temple of the God of War, those of great warriors being of as

notorious repute, and as widely feared, as the masters who wielded them.

Broken bones were a common occurrence in club fighting, and were

effectively splinted when not too badly shattered. Crushed fingers, an

occupational hazard of the club fighter, simply were amputated on the

spot by the injured man, using a kai shell. |

|

|

|

|

Fijian Hardwood War Clubs |

|

I Tuki - Battle Hammers (Skull Crushers)

Buried with Chiefs or Great Warriors

Borne by the Ghost for the hazardous journey to Balu . . . the Afterlife |

I Kolo - Throwing Clubs

Hurled with Great Precision

Favorite Implement of Assassination |

|

Fijian Hardwood "Totokia" Beaked

Battle Hammer |

|

|

Like other Fijian weapons

Spears were made within strictly formal, traditional types, and

categories

One particularly horrible spear variety

Made of a wood which swelled and splintered when wet

Bursting within the bloody wound

|

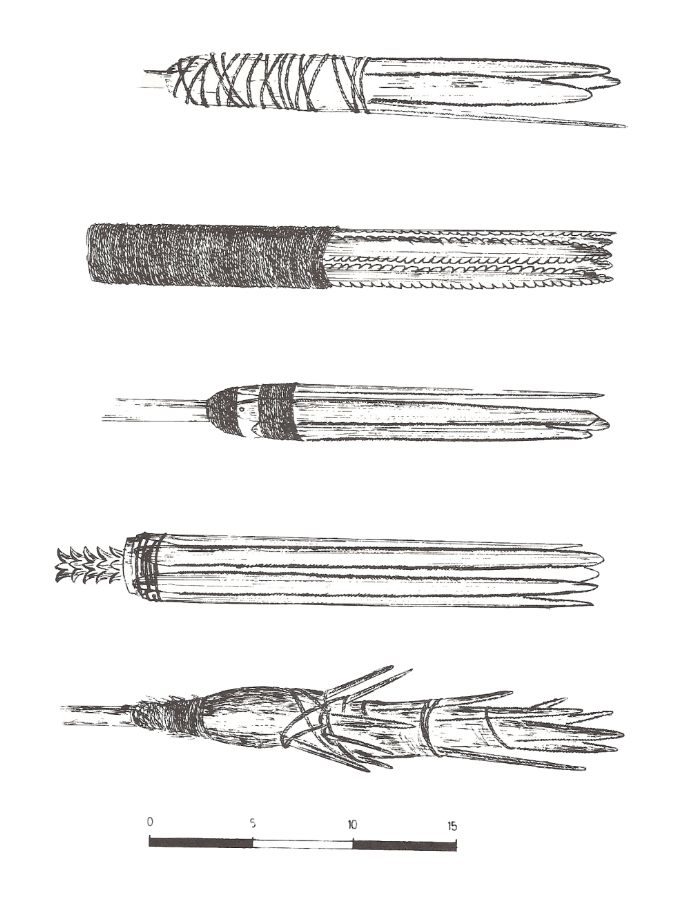

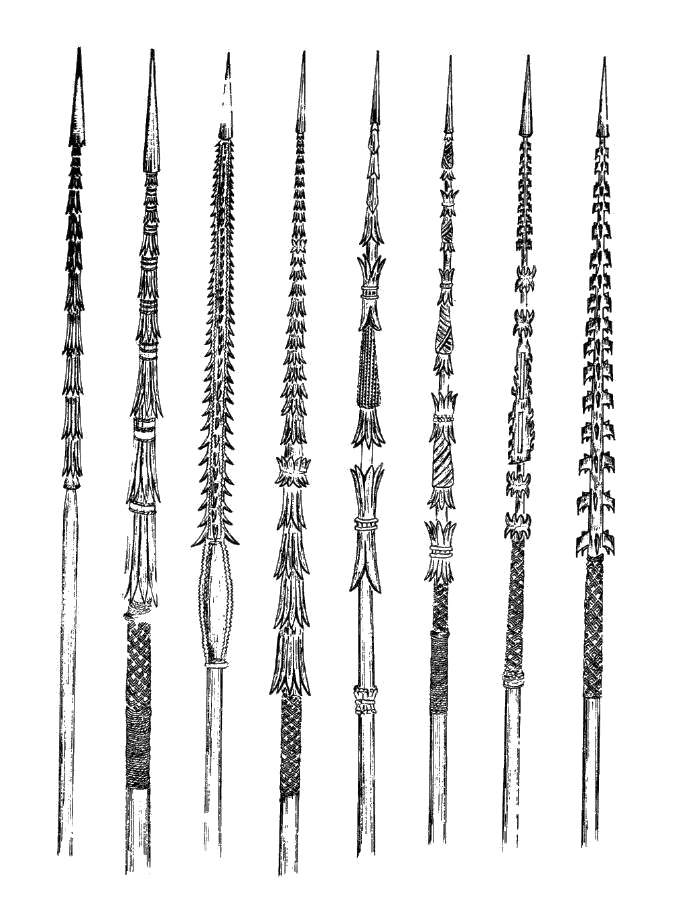

| "Of Fijian spears or javelins there is a great variety, having from

one to four points, and showing a round, square or semi-circular

section. Some are armed with the thorns of the stingray, some are

barbed, and some formed of a wood which bursts when moist so that it can

scarcely be extracted from a wound. They are deadly weapons, generally

of heavy wood, and from ten to fifteen feet long. One variety is

significantly called 'The Priest is too Late'." - Reverend Thomas

Williams . . .1884 |

| Throwing spears or Moto were major Fijian fighting weapons,

ranging in length from 1.5 to over 4 meters, most being at least 3

meters long. They were used in high numbers until the end of traditional

Fijian warfare, though they gradually became scarcer as the musket

became more and more common on the battlefield. |

| All Fijian spears other than Saisai, can generally be said to

have been made of a single length of wood, with the head and barbs

carved from the shaft. The multi-pronged Saisai was unique

among Fijian spears in that it was made up of several pieces of wood,

three or four long prongs. The heavy Saisai were designed and

used for war. To render them more dangerous each prong of the Saisai

was commonly tipped with a single stingray tail spike. This spear

was much used by chiefs. Similar, lighter spear tips were used for

fishing and were called by the same name.

Timbers used for the more elaborately barbed spears included a variety

of hardwoods, but principally Sacau or Bulu (Palaqutum

hornei), a dense, heavy wood which was soaked in water prior to carving,

and indeed could be stored underwater for many years without rotting.

Other utilized hardwood trees included, Vesi or Greenheart (Intsia

bijuga), Bau (Pittosporum brackenridgei), Makita (Parinarium laurinum),

and Vesivesi (Pongamia pinnata). In addition to these, a variety of palm

woods were commonly used for plainer javelins, including the Balaka

(Balaka seemanni). These palm wood spears are easily recognized by the

black and brown stripes running down their shafts.

The heads of the spears were generally round in section, inflicting a

puncturing rather than a cutting wound. The lack of sharp cutting edges

to the head meant the spear was unlikely to induce instant and shocking

massive bleeding unless it hit a major organ or blood vessel. Since the

spears could not be relied upon to take instant effect it was desirable

to make their extraction from the wound more difficult. Therefore, the

spears had heavy, exaggerated barbing of the spearheads. Extraction of

the spear from a body wound by pulling back on it was a virtual

impossibility without a major surgical operation.

In addition to these wooden barbs, the Fijians commonly tipped their

spearheads with a circlet of barbed stingray tail spikes or

Voto-ni-vai. |

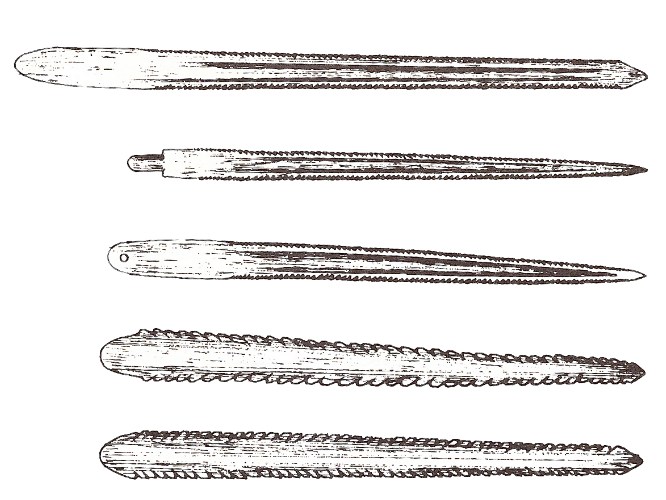

Fijian Spear Tips - Voto-Ni-Vai (centimeters) |

| They penetrated the wound as part of the spearhead but flared out

and remained within even relatively shallow wounds, sliding off the

spearhead as the weapon was withdrawn. The points were obtained from the

tails of stingrays, which are armed on the upper surface towards the

base with one or more large bony and serrated spikes, which can cause

painful and dangerous wounds. The points broken off in the wounds, the

barbs require surgery to remove them safely. These stingray tail spikes

were in great demand as spear and arrow points. |

Stingray

Tail Spike - Arrow and Spear Points |

|

| According to A. H. Ogilvie . . .1924, "the Voto-ni-vai or thorn of

the skate . . . . was a splendid assassin's dagger, and the man who had

that thrust into his neck or abdomen while asleep would be very unlikely

to recover." |

|

|

The Fijian spear was mostly thrown from the unaided hand of the

warrior. But sometimes throwing cords and throwing sticks were utilized

to propel the fighting spears over longer distances. The knotted end of

the cord was wound once round the spear shaft, the cord passing over the

knotted end so that while it was kept tight it gripped the shaft without

having to be tied, but fell loose if the string was allowed to slacken.

The length of the cord lay along the spear shaft, its looped end being

placed over the index finger of the throwing hand.When the spear was

thrown the looped end of the cord remained attached to the index finger,

the knotted end automatically whipping free from the spear shaft after

the spear left the hand. The cord thus lengthened the throwing arm, and

gave the spear a revolving motion like that of a rifle bullet. This

greatly increased range and velocity.

Fijian spears were also held for stabbing and thrusting as

circumstances warranted. |

| As the opposing forces closed to within twenty meters and less, the

spearmen poised and quivered their spears ominously in an attempt to

paralyze their foes, then suddenly hurling them with great force and

accuracy, and men skillfully dodging them at the last moment.

Spears were of great value in defensive warfare, being hurled out

onto exposed attackers from behind fighting fences and from the gate

platforms.

Spears were often used as incendiaries by attackers. Pieces of barkcloth

or dry grass were to their points and ignited. The flaming missiles were

then hurled over the fighting fence to land among thatched roofs within,

setting them ablaze.

Warriors usually carried a war club or battle-axe in addition to a

bundle of spears. It was traditional to rush in and and club a man after

he fell from a spear, as there was more credit and status pertaining to

a war club.

As with the war clubs the various Fijian fighting spears figured

prominently in dance and ceremony, as well as on the battlefield. They

also had a religious role in the construction of Temples, Bure Kalou.

Spears were decorated for dance and ceremony. The heads and barbed

sections of the spears were often gaily painted with red, white, yellow

or blue paint. Brightly colored Parrot feathers were tied in little

puffs to the spearheads.

During the nineteenth century bayonets and crude iron spearheads made by

ship's blacksmiths were commonly used as points on the traditionally

wooden headed fighting spears. |

|

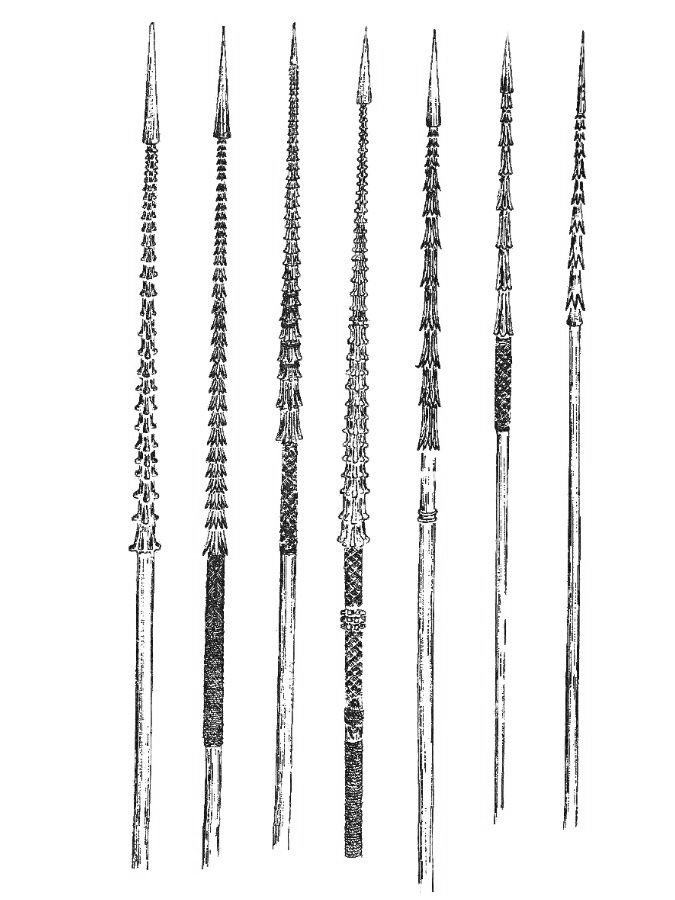

Fijian Spear Types (Sokilaki, Sirusiru, Se-ne-nui, Kaka) |

|

Extreme examples of the Sokilaki type spear

(First 4 Spears)

Sirusiru the barbs of which point both forward and backward to

make extraction from a wound more difficult (Next 2 Spears)

Se-ni-nui - literally "the coconut flower", a rare form (7th

Spear)

Kaka was a common type, characterized by its heavy, hooked barbs

(8th Spear) |

|

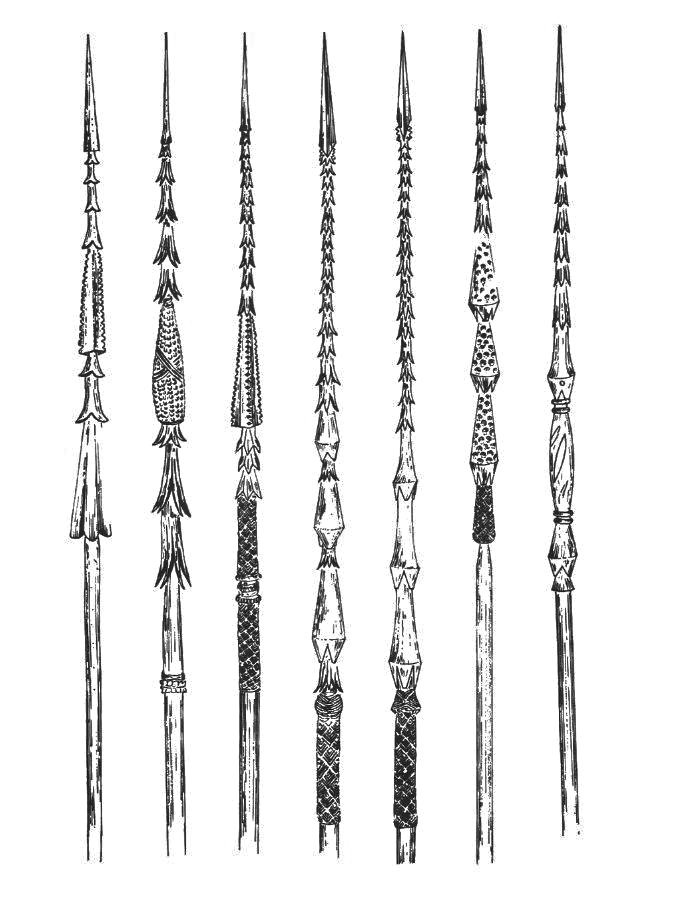

Fijian Spears (Tavevatu) |

|

Unknown types for first three spears.

Tavevatu - A common spear type. It is characterized by the series

of cones beneath the barbs, but more particularly by its head, which is

of quadrangular or diamond shaped cross-section, not round in cross

section like the heads of the other spear types. |

|

Fijian Sokilaki Spears |

|

Sokilaki - Showing the range in type of these

multibarbed fighting spears. |

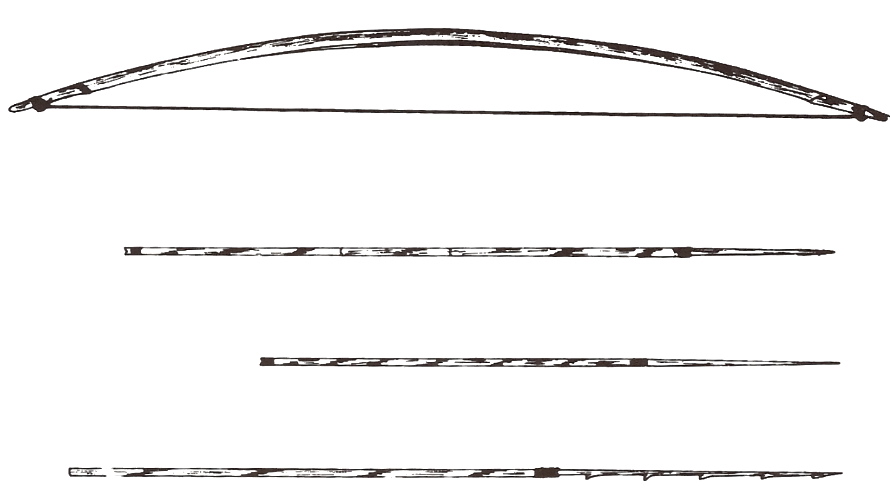

| The bow or Dakai was a major Fijian fighting weapon before it

was gradually replaced by the musket. Fijian bows were widely used for

hunting, fishing and war. Typically between 1.5 to 2 meters in length,

most war bow staffs had a groove running down much of the length of the

inside or belly of the bow. Fijian bows were either straight staffs,

plain bows or reflex.

Bows were used in both land and sea fights, battle usually commencing

with a shower of arrows and sling stones in pre-musket warfare. Bows

were used by women and children to defend their town from behind its

fighting fence. Bows were of particular value in attacking and defending

fortifications, in ambush, and in bringing down fleeing enemies. Fire

arrows were used to burn a town into submission. |

|

|

In Fiji, the usual method of bow making was to split a naturally

curving Mangrove root or branch lengthways, and to use the two

strips so obtained to make two bows, unless one half was rejected by the

craftsman. The groove on the belly of Fijian bows is caused by the

cleaning out of the sapwood or tube of pulpy pith which runs down the

middle of the Mangrove root, because in many cases the

root was not split dead centrally. The root strip was roughed out with a

adze, the sap groove cleaned out, and the stave scraped smooth with

bivalve shell scrappers. Ash was then rubbed into the wood of the staff

and it was smoked and oiled. The bow string was plaited in a two or

three string strand from the inner bark of the wild hibiscus, other

barks occasionally were used.

Bows were generally stored unstrung, only being strung when it became

necessary to shoot them. |

|

|

| Fijian reed war arrows were usually just over a meter long, into one

end of which was inserted a hardwood spike, usually slivers of

Mangrove or other hard woods, with or without a small stingray

tail-spike point to make extraction from the wound more difficult, or

were heavily barbed along one side, the backward raking barbs being

thinned down where they rose from the shaft of the arrowhead so they

snapped off readily within the wound. Unbarbed arrowheads had a thin

fish bone inserted on either side, just behind the tip, pointing

backwards and almost flush with the shaft so that they would not snap

off while penetrating the body, but would effectively prevent the arrow

from being pulled back out of the wound. |

|

|

The bow took a more deadly toll days and even weeks after the

conflict, as barbed arrow heads in the body could only be removed by

surgery, while punctured lungs and guts led to lingering deaths. The

Fijians were well aware of the absolute necessity of removing all

particles of an arrow or spear from a wound, and knew full well that the

dreaded lockjaw or tetanus was most likely to arise from the deep

puncture wounds inflicted by their arrows. The Fijians developed

sophisticated surgery to deal with combat wounds caused by arrows and

barbed spears.

In an attempt to increase the potency of their arrows, the Fijians

sometimes coated their arrowheads with vegetable poisons, the most

widely known of which was the gum of the Mavu-ni-toga Tree (Antiaris

toxicaria), a rare tree in Fiji, and one specially cultivated in temple

compounds. |

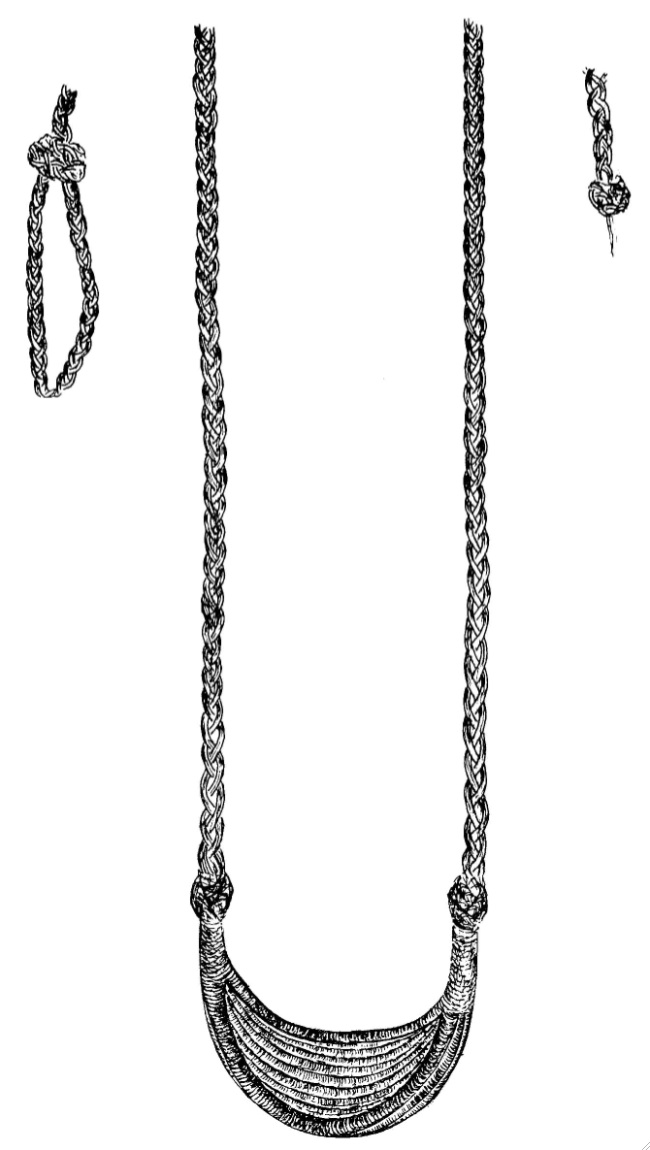

Fijian Sling |

Early accounts by traders and beachcombers show that

battle usually opened with volleys of sling stones and arrows before the

warriors closed to fight at close quarters with spears and clubs.

Clubmen were also armed with slings, as the sling was particularly handy

providing warriors with an effective missile weapon which when not

needed could simply be tied round the waist or upper arm, not impeding

the use of the war club in any way.

The strings of the sling were plaited from the inner bark of wild

Hibiscus (Hibiscus tiliaceus), and in rare cases from human hair. Fine

twine from the Wa Yaka Vine (Pueraria lobata) was used to cover and bind

together the several parallel coir-sinnet cords which made up the basket

or stone pouch of the sling. The two throwing strings which ran up from

either end of the basket, one ending in a finger loop and the other in a

knot, were each generally some 60 to 70 centimeters long.

In using the sling the finger loop was placed over the middle finger of

the throwing hand, the knot of the other cord being grasped between the

thumb and index finger, and the stone placed in the basket. The slinger

swung the sling round once above his head than snapped out his arm and

released the knotted cord, the sling jerking out to its full extent,

sending the stone towards its target.

Hibiscus tiliaceus |

|

Antiaris

toxicaria |

|

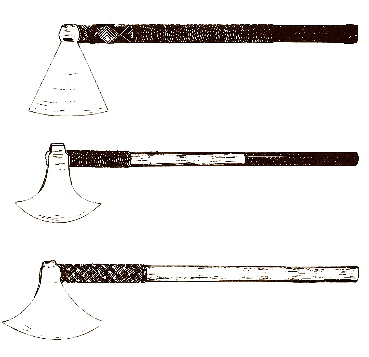

During the nineteenth century heavy axes, hatchets,

knives and swords of various form were introduced to Fiji by European

traders and many were absorbed into the Fijian armory. |

Fijian Battle Axes |

Swords - The swords, mainly sabers and cutlasses saw only

limited use by Fijian warriors. The unpopularity of these weapons can be

attributed to the stroke and grip of the weapon being quite unfamiliar

to the Fijian warrior. An awkward weapon to the Fijians, the sword had

little advantage over the two-handed war club. Knives - The

warriors liked the long bladed butchers knives better and used them

frequently in close quarters melee fighting. With the razor sharp sheath

knife a warrior could step inside the two-handed swing of a clubman,

unused to such a technique, and plunge your knife through the vitals.

Tomahawks - Tomahawks were popular with Fijian warriors, but the

lighter hatchets were less so, because they felt too light and flimsy

for warriors accustomed to swinging hefty Fijian war clubs.

Battle Axes - It was the heavy broad blade battle axes that

were the most popular European weaponry introduced to Fiji. This was

probably because they were used in the same manner as a two-handed war

club. The tomahawk and battle axe heads were fitted by the Fijians with

their own round sectioned hard wood handles, which were carved with a

zig zag grip and multi-colored binding, as was the case with their war

clubs. By the mid 1870's, the axe was replacing the Fijian war club as a

close quarter weapon. |

|

|

|

| An American ship, hired to bombard the Fiji Island of Bau, calmly

anchored offshore and fired a broadside into the town. But the local

beachcombers, white residents of Bau at the time, prepared a response. A

large cannon was brought to bear on the ship. The second shot struck the

jib-boom and the captain fearing he might be disabled slipped anchor and

sailed out. |

Cannon fire was among the first gunfire the Fijians were

subjected to and its reputation spread rapidly.

Brass and iron barreled, muzzle loading, smooth bored cannon, were used

by the Fijians to a limited degree in their nineteenth century wars.

These cannons ranged in type and calibre from light Pivot Blunder Busses

and Swivel Guns (originally mounted aboard ships as anti-personnel

weapons), and up to three and four pounder cannons mounted on wooden,

small wheeled naval truck carriages, some of which were inlaid with

bone, in the same fashion as war clubs. |

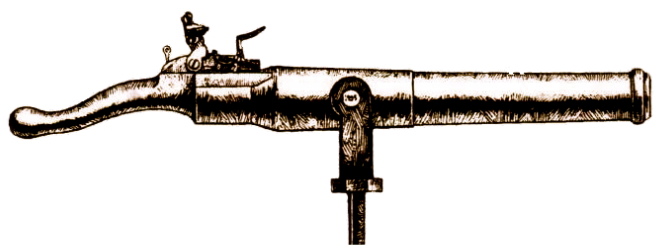

Swivel Gun |

The projectiles used in cannons in Fijian warfare were generally

based on conventional European naval projectiles of the time. At long

range against buildings, earthworks or large canoes, a single heavy cast

iron ball or round shot was loaded. The Fijians, and beachcombers

frugally employed lighter, less effective, rounded river stones when

proper cannon balls were in short supply, which was usual.

Case or Scatter Shot was used at closer ranges against bamboo and

reed fighting fences, canoes and massed groups of warriors, the cannon

acting like a gigantic shotgun. Scatter shot consisted of grapeshot

(tubular canvas bag filled with several tiers of iron balls or musket

balls), which was rammed home over the cartridge, in place of the round

shot. These scatter shot loads were devastating against canoe crews or

groups of warriors, from close range to out to well over 200 meters,

depending on the gun.

Also used was Canister, which consisted of a tin can or cylinder

filled with musket balls. Langrage was a canister filled with

irregular pieces of iron to bring down rigging and sails. |

Swivel Gun Frontal View |

With canister, grapeshot and langrage the containers burst on

leaving the muzzle, spewing forth a metallic and rapidly spreading hail

of small ball, each perfectly capable of killing or maiming.

It was common practice to double shot the guns, meaning to ram in two

loads of grape or canister, or a load of scatter shot with a round shot

together, to render them more effective.

Most merchant ships trading in the islands in the first half of the

nineteenth century carried a defensive armament of cannon, and nearly

all the cannons used in Fiji were obtained from shipwrecks or traded

from the captains of foreign vessels.

Due to their weight, cannons were largely confined to fortifications and

siege warfare in less rugged terrain, mostly near the coast or along

navigable rivers. Only a few were transported further inland. |

|

Colt .44 Caliber Army Model . . .

circa 1860 |

In early 1800 the American schooner "Argo" was wrecked on the

Bukatatanoa Reef in the extreme southeast of Fiji. The Argo brought to

the islands the first of a series of foreign diseases, which were to

decimate the Fijian people, and introduced the flintlock musket to the

region.

It was the sandalwood merchant ships that acquainted the Fijians with

firarms. First encounters scared off Fijian war canoes. But by 1808, the

sandalwood cargo ships captains were finding it profitable to help the

local chiefs in their wars. Their crews, with musket and cannon, fought

as mercenaries with the allied natives, in return for bigger and more

easily obtained cargoes. |

|

US M1816 Flintlock Musket |

Another source of firearm education were the "Beachcombers". Lured

by the chance of an easy, lawless life, with multiple wives, and perhaps

more specifically, the treasure hunt for the thousands of silver pillar

dollars wrecked with the brig "Eliza" off Nairai, in 1808, came motley

bunches of shipwrecked sailors, escaped convicts, and ship deserters.

They formed small beachcomber communities under the protection of some

of the major chiefs. They went native and dressed like the Fijians and

"followed the customs of the aboriginals" so as not to be too

conspicuous a target in a fight, and so certainly be killed.

The largest and most violent band established itself on Bau Island,

which by virtue of its canoe fleets and maritime strength held sway over

scattered parts of Fiji. The most notorious and able of this assortment

of multiracial adventurers was one Charles Savage, a survivor of the

Eliza wreck. Another was Paddy Connor, an Irish rogue and lying escaped

convict, who survived on the islands more than thirty years. |

Pepperbox Revolver |

At first muskets and other firearms were only in the

hands of these ragged mercenaries and the crews of trading ships. For

twenty years few but foreigners and the chiefs of larger coastal powers

had the opportunity or dared to use them. Up to about 1830 the musket

was still a novelty over much of Fiji. But its fearsome reputation had

preceded it to most areas, which probably added to the spectacular

results it often achieved when first introduced to an area. Later,

particularly in the coastal areas, where the novelty soon wore off, the

guns passed into the hands of more and more warriors, other than heroes

and chiefs.

"Amongst the booty from the ship were many casks of powder of whose

explosive nature the natives had little knowledge, and of its extreme

danger when accumulated in large quantities, little conception. In one

dwelling . . . were a number of kegs of powder promiscuously placed upon

the floor, in the center of which a fire was kindled . . . . loose

powder was scattered about, and the proprietor . . . . sat on a keg of

powder before the fire, composedly smoking his pipe." W. D. Dix of the

ship "Glide", 1848. |

By 1840 the musket was an increasingly common weapon in the hands of

coast and island dwelling warriors and was even infiltrating remote

mountain districts in the interior of the major islands. But the

traditional bow and sling remained in common use in combat until well

into the 1850's, and played their part in mountain battles through the

sixties, never being entirely replaced.

By 1850, however, the musket was the predominant projectile weapon of

the coastal warrior. It must be stressed however, that firearms never

completely replaced the indigenous weapons in Fijian warfare, clubs and

spears still being the most numerous weapons on the battlefield as late

as 1870.

From their introduction early in the century through to the late 1850's

the Fijians generally obtained their muskets and ammunition by

plundering shipwrecks or in trade with merchant ship captains. Later

they received muskets and ammunition for bringing in trade goods. The

trade in muskets, powder, ball, flints and percussion caps was only

finally stamped out, along with Fijian warfare, after Fiji became a

British Crown Colony in 1874.

The firearm most commonly used in Fijian warfare was the muzzleloading,

smoothbored flintlock musket. Pistols were often worn by chiefs in time

of danger and intrigue, but never caught on with common warriors, who

preferred traditional weapons at close quarters.

Lieutenant Wilkes . . . 1845, of the U.S. Exploring Expedition, who in

his punitive raid on Aalolo in 1840 became convinced that the Fijians

could dodge a gunshot, noted that: "Our party having approached within

seventy feet of the stockade, opened its fire on the fortification. Now

was seen, what many of those present had not believed, the expertness

with which these people dodge a shot at the flash of a gun. Those who

were the most incredulous before, were now satisfied they could do this

effectually."

Few Fijian warriors ever attained any real accuracy with the musket. The

warriors tended to jerk off a shot as the gun came to the shoulder. The

bullets used by the warriors were far from standard and hardly conducive

to accuracy. Not knowing how to cast lead bullets, they were fond of

scatter shot loads, which were a crazy mix of old nail heads and other

scrap, pebbles, or even pieces of broken bottles. |

|

.jpg)

.jpg)